Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Materials

Soaps and Detergents

by Michael McCoy

January 26, 2004

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 82, Issue 4

"Chemistry is back," declares thomas Müller-Kirschbaum, head of worldwide production and technology development for the laundry and home care business of Henkel, the German consumer products giant. Müller-Kirschbaum, a veteran of the soap and detergent scene, is talking about the thrust today in Henkel's R&D labs after several years in which new product forms--gels, sachets, tablets, and the like--seemed to be all the rage.

COVER STORY

SOAPS AND DETERGENTS

This focus on chemistry is occurring across Henkel's product portfolio, Müller-Kirschbaum says, but it doesn't necessarily mean more chemicals in the retail box or bottle that the consumer buys. "Our direction is smart chemistry," he says. "The amount of material in our recipes is not going up, but there is a smarter

kind of chemistry in the products."

Chemical companies may be disappointed to hear that Henkel won't be packing in more ingredients. Still, Müller-Kirschbaum's description of Henkel's R&D direction should give some comfort to firms that supply cleaning product companies like Henkel with performance-enhancing ingredients. Suppliers' laboratories are full of innovations that can improve consumer product performance, but many makers of these products are not eager purchasers these days.

That's because a poor economy and big retailers with their own private-label brands have combined to put a price squeeze on home care products, particularly laundry detergents. This pressure starts on store shelves and cascades through consumer product makers and on to the chemical industry.

"The pressure is on for the innovators -- the Procter & Gambles, the Henkels, the Unilevers -- to put products out there that meet price constraints and still secure a place in the market," says Mike Cheek, head of home and fabric care in North America for Ciba Specialty Chemicals. "There is still room for innovation, but it must be delivered at the prices that consumers pay today."

That same pressure is on chemical companies like Ciba as well, Cheek acknowledges. These firms are responding with their own variations on smart chemistry--lower priced versions of premium ingredients and enhanced delivery of existing ones--that promise innovative new effects at little or no additional cost.

Nowhere is the pressure on retail prices more evident than with Procter & Gamble's value-priced Gain, the fastest growing U.S. laundry detergent brand last year. J. Keith Grime, vice president of R&D for P&G's global fabric and home care unit, says Gain's success is based on "knowing the consumers for whom the product is targeted and delivering exactly what they need at a price they can afford so that they recognize the value."

INTERESTINGLY, although Gain is a midtier brand, it draws on some of the chemistry developed for P&G's premium Tide brand. For example, Grime says the powdered variety of Gain now contains a proprietary, quick-dissolving alcohol sulfate surfactant developed with Shell Chemical and launched in 2002 in Tide. And Gain powder with bleach contains nonanoylbenzene sulfonate, the high-performance peroxygen bleach activator long used in Tide with Bleach.

Likewise, Gain Fabric Enhancer is a new fabric softener that uses diethylester dimethyl ammonium chloride, the same softener active found in P&G's premium Downy brand.

Of course, P&G reserves some technologies for Tide and for Ariel, its premium European brand. In France, for example, the company recently introduced Ariel Style, which Grime calls the first detergent to offer a fabric shape retention benefit. The technology, called Fiberflex, was developed in partnership with one of P&G's chemical suppliers.

Grime describes Fiberflex as a novel cationic aminosilicone that deposits well on fabrics, even in the presence of high levels of surfactant, a historical limitation of such chemistry. He says the patented structure--an amino/ethylene oxide backbone with poly(dimethylsiloxane) spacers--can be thought of as repeating amino groups separated by silicone springs that impart the shape-retention benefit.

Also being introduced in P&G's flagship brands is a new enzyme combination of pectate lyase and mannanase. Grime says this combination targets the pectins, mannins, and guars that are present in many food stains, either from the food itself or from thickeners used with them. Not only are these substances difficult to remove, they leave residues after washing that can act as "magnets" and attract other stains during wear, he says.

Another premium brand innovation from P&G is an ethoxylated quaternized sulfated amine that the Tide and Ariel franchises are incorporating as a cleaning polymer. According to Grime, this technology improves cleaning performance on two fronts: through improved soil suspension capability and improved removal of outdoor soil stains, a perennial laundry problem.

Like P&G, Henkel also introduced new technology to its premium detergents during 2003. Müller-Kirschbaum says the company completely reworked the heavy-duty laundry detergents it sells in Europe by employing the smart chemistry concept in two different ways.

Henkel's powdered detergents no longer contain any nonsoluble materials, which can deposit as residue on fabrics. Notably, last year Henkel phased out the zeolite builders that it pioneered decades ago when Europe banned laundry phosphates. Müller-Kirschbaum says the firm has returned to the soda ash/silicate combination common before phosphates, but now with the assistance of special cobuilders and other trace ingredients that prevent the mineral precipitation that plagued the formulas of old.

The second chemistry change, launched early this year, is a short-wash-cycle formula for Henkel's flagship Persil detergent brand. Highly soluble, the formula is designed to work with the shorter wash option that is showing up on Europe's front-loading washing machines. In concert with the new formula, the recommended dosage of the Megaperls variety of Persil has been cut from 75 g to 68 g. "It has 10% less chemicals but smarter chemistry because the performance is better than before--especially in short and cold wash cycles," Müller-Kirschbaum says.

Tide, Ariel, and Persil aside, however, successful premium laundry detergent brands are few and far between these days. Indeed, figures from market researchers at Information Resources show that sales of Unilever's premium detergent, Wisk, fell almost 16% during 2003, although the brand is still the fourth largest selling U.S. liquid. Instead, Gain and Dial's value-priced Purex brand were the growth leaders last year.

Demonstrating the appeal of midtier brands, Henkel announced in December that it is acquiring Dial for $2.9 billion as part of a major push into the U.S. market. Interestingly, Henkel and Dial teamed up in 2000 in a joint venture to create a premium version of Purex called Purex Advanced. That effort failed, but Müller-Kirschbaum says the acquisition opens broader possibilities in the laundry detergent market.

"Dial is in the value-for-money area, whereas Henkel normally has a premium strategy," he says. "We can learn a lot from Dial on how to make a profitable business in value-for-money." Dial brands might become conduits for Henkel technology, he adds, or Henkel brands could be launched in new markets through Dial's distribution channels.

Mindful of such developments, chemical companies are turning their efforts to developing quality ingredients that are cost-effective even in midtier detergent brands. Kevin Beairsto, marketing manager for detergents at Alco Chemical, a division of ICI's National Starch & Chemical that focuses on specialty polymers, says there has been "a marked improvement in value brand performance over the past decade, and much of the improvement has come from the use of premium ingredients."

Beairsto says Alco develops ingredients for such products with an eye to the value of the total formulation more than the cost of individual ingredients. For example, he says the firm recently launched a polymer designed to improve anti-redeposition in liquid laundry systems that costs, on a discrete basis, about 50% more than competing commodity polymers.

"Initial reaction from our customers is almost always, 'There is no way we can afford that kind of additional cost in our formula,' " Beairsto says. "But when the customers evaluate the polymer, they find that it allows them to reduce levels of other materials in the formulation and that it is effective at much lower levels than traditional commodity materials."

IN OTHER CASES, specialty chemical suppliers rework a premium product into a cheaper version that can be used in lower priced brands. Herman Mihalich, home care vice president for Rhodia, says his company is in the process of launching a cost-effective extension to its well-known Repel-O-Tex line of polyester-based soil-release polymers.

Soil-release polymers work best on polyester garments, where they deposit in the wash and then act as a sacrificial layer to which soil adheres during subsequent wearing. Mihalich says the new product, Repel-O-Tex SRP-6, is a higher solids version intended to bring premium-type benefits to midtier brands.

The next best thing to a low-priced product that performs like an expensive one is delivering the expensive one more cost-effectively. Improved delivery through encapsulation, polymer matrixes, and other means is an area of intense research among specialty chemical companies. While this search for innovative delivery techniques is not new, companies such as Alco, Rhodia, International Specialty Products, and Ciba have stepped up their efforts over the past year.

For Alco, effective product delivery is both a challenge and an opportunity. Beairsto explains that the company has technologies that could solve many consumer problems. "However, much of the chemistry is fairly expensive," he says. "And because many of the polymers are not inherently drawn to the surface being cleaned, much of the material--and the expense--is drained out with the wash water."

Beairsto says Alco is working on encapsulation and targeted delivery of polymers--as well as fragrances and other actives--with sister ICI companies. Dallas Hetherington, business manager for Alco's encapsulation and delivery systems team, notes that National Starch has a long history in specialty encapsulation starches for the flavor and beverage industries. "Fragrances can be quite similar to flavors, so it is not a big leap for us to be involved with fragrance encapsulation," he says.

Alco recently licensed a family of delivery technologies from Salvona LLC and is developing them with a focus on fragrance for detergents and fabric softeners. And Hetherington says National and Alco will be leveraging fragrance expertise in Quest, ICI's flavors and fragrances unit, and elsewhere in their parent company.

ICI companies aren't the only ones redirecting delivery technology from other businesses to home care. Rita Köster, global marketing director for home and fabric care at Cognis, acknowledges that her firm's encapsulation portfolio is today mostly directed at the personal care market. But with aesthetics driving purchasing decisions even in the cleaning products aisle, she says her unit is "giving encapsulation technology a high priority."

Likewise, Sotiri A. Papoulias, global marketing director for ISP's performance chemicals business, says his company has developed an ingredient delivery system based on microemulsion technology originally developed to deliver hydrophobic agrochemical actives in water-based formulations. Called Microflex, the system is based on n-octyl pyrrolidone and a naturally derived surfactant.

Papoulias says the anionic surfactants prevalent in laundry detergents tend to compromise fragrances and limit fragrance delivery to the clothes being washed to just 15 to 20%. He acknowledges that Microflex isn't a cure-all but says even a small benefit is of great interest to ISP's customers and that some have been testing the product in liquid detergents since mid-2003.

Thomas McGee, head of global technology and innovation for the fragrance division of flavor and fragrance giant Givaudan, says getting fragrance from a liquid laundry detergent onto fabric is indeed a Holy Grail of the detergent industry. "We currently fragrance fabric by the use of water-insoluble materials with low perception thresholds," McGee says. "However, the level of fragrancing we achieve is far lower than that achieved from fabric softeners," which are based on cationic surfactants.

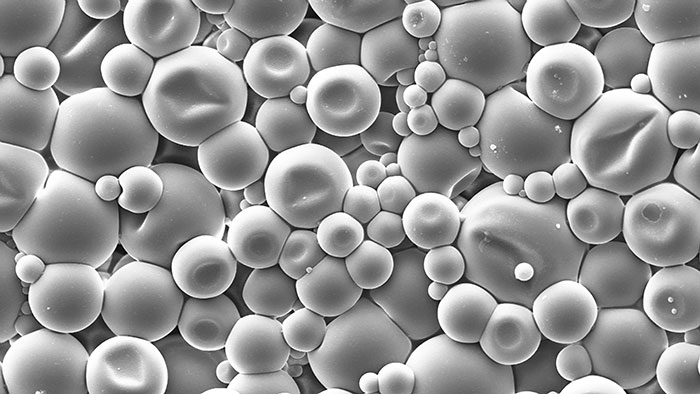

POWDERED detergents are a different story. For them, Givaudan recently launched Granuscent encapsulation technology, which is designed to protect volatile fragrance materials and those that are attacked by other ingredients. McGee says Granuscent granules are made by spray-drying an emulsion containing the desired fragrance to form a glassy hydrophilic matrix. This is then agglomerated using a second emulsion. Stability and release are controlled by selection of encapsulation materials in both emulsions.

According to McGee, the technology has been evaluated by major soap and detergent manufacturers and is now in a large consumer test. Granuscent adds cost, he acknowledges, so it must provide a perceived consumer benefit or help support a strong advertising claim. One way to offset this cost, he adds, would be to use the technology to co-encapsulate nonfragrance detergent ingredients.

Advertisement

Another flavor and fragrance developer with a strong encapsulation effort is Symrise, which was formed last year from the merger of Dragoco and Haarmann & Reimer. Keith McDermott, the firm's vice president of applied research, says Symrise's starch-based InCap and polyvinyl alcohol-based PolyCap products are leading encapsulation systems for dry products. Its SymCap system, which can contain urea-based resins or natural gums, is geared toward liquids.

"Symrise is the largest producer of spray-dried fragrances for personal care," McDermott says, "and we are leveraging our personal care technologies into home care." For example, encapsulation allows companies to deliver volatile or light fragrance notes that could not be used in fabric care before--an ability, he explains, of great interest given the proliferation of brands that are often differentiated on the basis of fragrance.

Ciba is pursuing fragrance delivery from another direction--extending scent longevity in the package. In October, the company launched technology it calls ESQ--for excited state quencher. Cheek explains that ESQ is not an antioxidant or UV absorber but works instead by quenching the excited state that molecules reach when they are exposed to light or high temperatures. Although Ciba researchers developed ESQ primarily with color stability in mind, he says the company is attracting a surprising amount of interest from customers interested in preserving fragrance in home and personal care products.

Cheek adds that Ciba researchers in Tarrytown, N.Y., are also in earlier phases of work on delivery polymers and encapsulation technology. "There are a lot of things you can deliver in capsules. The question is commercial viability," he observes.

Ingredient delivery for laundry detergents may be the most visible R&D effort at the moment, but plenty of smart chemistry is occurring across the home and fabric care business. Among the chemistry-driven new products in P&G's stable is Cascade ActionPacs, an automatic dishwashing detergent that comes in a dual compartment pouch containing both powder and liquid phases. Grime says innovations in film technology are allowing the company to deliver a combination of noncompatible actives--such as bleaches and blooming fragrances--in one product.

On another front, P&G worked with Rhodia to develop its new Mr. Clean AutoDry car wash, which promises a spot-free shine with no hand drying. According to Rhodia's Mihalich, the product's claim is made possible by a new Rhodia polymer called DryRinse that is an outgrowth of the firm's Mirapol Surf S family of hard-surface cleaner ingredients based on acrylic polymers and copolymers.

Using inorganic chemistry, Henkel achieves a similar spot-free effect in a new Sidolin-brand glass cleaner. Müller-Kirschbaum says the cleaner contains a nanoscale additive, developed with an external partner, that prolongs the cleanliness of window glass by enhancing raindrop runoff. Glass manufacturers such as Pilkington and PPG Industries have developed titanium dioxide-coated glass with similar attributes, but Müller-Kirschbaum says Sidolin's chemistry is different.

TRYING TO EMULATE the success of P&G's Swiffer floor cleaner line, consumer product makers are developing cleaning products based on nonwoven fabrics with the help of specialty chemicals companies. For example, Cognis' fastest growing division during 2003 was care chemicals, and Köster attributes the success to products like Dehypound W, a family of ready-to-use concentrates being adopted by producers of nonwoven wipes. Köster says the concentrates save formulation steps by delivering effects such as cleaning, gloss retention, and streak elimination in a single product.

John C. Dougherty, Degussa's business line director for personal care, says his business has set up a cross-functional group of researchers and marketers to pursue innovations for the nonwoven wipes market. Among the product attributes they are trying to create for customers are absorbency, fast-drying, and active ingredient delivery.

The big household product makers will no doubt be receptive to specialty chemical company efforts such as Degussa's. P&G's annual report says the company has more than doubled the success rate of its new product initiatives, and Grime attributes this success in part to the help of such outside companies.

"We have long believed in strong collaboration with our suppliers," he says. "However, we have gone much further and developed 'research and development' into 'connect and develop' in which we use assets and knowledge from external sources much more than we have in the past. When used in tandem with internal sources, this results in maximum technological reach, creativity, and speed to the marketplace."

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter