Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Materials

What’s that Stuff

What's that stuff? Raincoats

Charles Macintosh's waterproof-fabric concept, patented more than 180 years ago, is still relevant

by Bethany Halford

June 12, 2006

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 84, Issue 24

Necessity, they say, is the mother of invention. So it should come as no surprise that the inventor of the modern raincoat, chemist Charles Macintosh, was a native of rainy Scotland.

Although Macintosh is considered the father of the raincoat−waterproof coats are still called mackintoshes in the U.K.−he was by no means the first to try to make water-resistant fabrics. As early as the 13th century, South American natives were coating cloth with natural liquid latex to make waterproof footwear and capes.

When Europeans tried to ship this latex back home, they found that the liquid decomposed. Bacteria attacked the natural rubber, rendering it useless. "It curdled," explains John Loadman, a retired analytical chemist and rubber historian who maintains www.bouncing-balls.com, a website dedicated to the history and chemistry of rubber.

What would-be waterproofers needed was a good solvent for making latexlike solutions with solid rubber. In 1748, French scientist François Fresneau devised a way to waterproof fabric based on the natives' techniques using turpentine as a rubber solvent. About 70 years later, Scottish surgeon James Syme, a contemporary of Macintosh's, found that the hydrocarbon mix known as coal tar naphtha readily dissolved rubber and could be used for waterproofing. Syme wasn't interested in commercializing this discovery, however.

Coal tar naphtha was one of the waste products from the conversion of coal into the gas used in streetlamps. Macintosh had a contract with the Glasgow Gas Light Co. to buy the waste products from this process. Principally, he was interested in extracting ammonia from this waste for his father's dye business. But he was still left with an abundance of coal tar naphtha.

Macintosh soon learned of coal tar naphtha's rubber-dissolving properties, and he found that fabric treated with this solution became waterproof. The fabric was sticky, though, and it had a foul smell. "Macintosh's brilliant idea to avoid the stickiness was simply to press two sheets of fabric together with the rubber sandwiched between them," Loadman says. "Unfortunately, the smell remained."

Macintosh patented the invention in 1823; however, it was anything but an instant success. The smell put most people off, and Macintosh's customer service skills were decidedly lacking. Sizable and steady demand from the armed forces and merchant navy was all that kept Macintosh's waterproof fabric business afloat. "I should imagine that the waterproofing properties more than compensated for one extra smell amongst many that the soldiers and sailors would be experiencing," Loadman jokes.

Others improved upon Macintosh's original invention, making the material lighter, more pliable, less smelly, and, as a result, more popular. A "cold cure" vulcanization process, in which the rubber was treated with a bath or the vapors of a sulfur compound eliminated the material's stickiness and, consequently, the need to use more than a single layer of fabric.

Advances in synthetic polymers and water-repellent coatings have since led to lighter, cheaper, and more colorful raincoats. But Macintosh's original idea is still evident in today's cutting-edge waterproof fabrics.

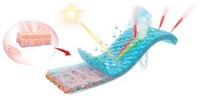

Tom Rosenmayer, a materials scientist with W. L. Gore & Associates, says the company's waterproof fabrics, including Gore-Tex, feature an advanced polymer membrane laminated between two pieces of fabric. "The major difference is that modern rainwear is not only waterproof but it also allows your perspiration to escape," he says. So you keep the rain off without getting sweaty.

This breathable fabric's architecture has a layer of hydrophilic polyurethane on top of the layer of fabric that lies against the skin. A layer of microporous polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) is placed on top of the polyurethane and just beneath the outer layer of fabric.

The PTFE, Rosenmayer explains, keeps rain out, while the hydrophilic polyurethane, which has a high diffusivity for water vapor, wicks away any moisture from the skin. "The inside of the garment is at a higher temperature than the outside of the garment," he says, "so the heat from your body provides the driving force to push the water molecules through the membrane."

Rosenmayer points out that the pores of the microporous PTFE provide a "comfort layer" of air. Out in the rain, the garment eventually will become saturated with moisture, which conducts heat away from the body. "If you didn't have that air, it would be really easy to get chilled," he explains.

Although W. L. Gore & Associates doesn't actually make any of the clothes that bear the Gore-Tex label, prototypes of all the garments made with their waterproof fabric are tested in the company's living-room-sized storm chamber. The nozzles on the ceiling and walls of this rain room spray mannequins and paid college students wearing the prototypes from every conceivable angle.

The chemistry and materials science of raincoats continue to evolve. The scientists who make Gore-Tex are trying to improve the material's breathability, Rosenmayer notes. They are also trying to apply their polymer membrane to a wider variety of textiles.

Durability and wear resistance are other areas of active research, Loadman adds. "But having said that," he quips, "which lady do you know who wants a coat that lasts more than a year?"

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter