Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

People

Ralph F. Hirschmann Award in Peptide Chemistry

January 16, 2006

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 84, Issue 3

Sponsored by Merck Research Laboratories

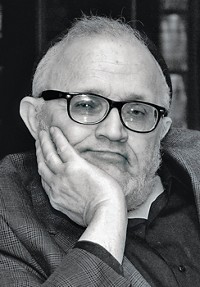

As a teenager, George Barany was something of a math prodigy, reading dense textbooks as if they were spy novels.

But while learning about the great mathematicians, Barany found to his chagrin that many of them did their best work in their 20s. "I was 16, looking in the mirror, and I didn't want to retire in 10 years," he says. Instead, Barany followed his parents into biochemistry, eventually becoming a leader in the field of solid-phase peptide synthesis.

True to his precocious form, he did so by skipping college and going straight from New York City's prestigious Stuyvesant High School to graduate school at Rockefeller University. There, he studied under R. Bruce Merrifield, who would go on to win the 1984 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. Barany earned his Ph.D. in biochemistry in 1977 at the age of 22 and stayed on in the Merrifield lab as a postdoc.

During Barany's first year at Rockefeller, Merrifield published a paper on the total synthesis of ribonuclease, a feat that seemed to Barany like almost the final word in peptide chemistry. "I thought it would be a one- or two-year detour for me," he says of his early peptide research. "It turned out to be more than 20 years."

In 1980, Barany joined the chemistry department at the University of Minnesota, where he continues to teach and carry out research as Distinguished McKnight University Professor.

Among his many scientific accomplishments, Barany, 50, has built upon Merrifield's work in polystyrene resin supports for peptide synthesis. Collaborating in the early 1990s with Fernando Albericio and Samuel Zalipsky, he came up with a polyethylene glycol-polystyrene composite support that is compatible with both hydrophilic and hydrophobic molecules. Later in the 1990s, he and Maria Kempe developed a new generation of supports called cross-linked ethoxylate acrylate resins, or CLEAR.

Other contributions to the synthetic chemistry toolbox include the development of linkers that are cleaved under mild conditions, the identification of unwanted reactions and ways to circumvent them, and the introduction of solid-phase synthesis methods to combinatorial organic chemistry.

In recent years, Barany has been applying his chemistry knowledge to biological problems. For example, Barany, Daniel Mullen, and University of Minnesota colleague Karin Musier-Forsyth recently made multi-milligram quantities of the nucleocapsid protein, a 55-amino acid molecule that plays a crucial role in the life cycle of HIV. And, teaming up with Clare Woodward and Gianluigi Veglia, he is applying his synthetic skills to the study of protein folding, which is at the root of diseases like Alzheimer's and mad cow.

Although an ambitious researcher, Barany takes his classroom and mentoring duties seriously. He's well-known at Minnesota, for instance, for the educational skits performed by his undergraduate chemistry classes. Charles M. Deber, a longtime colleague and professor of biochemistry at the University of Toronto, calls Barany "an exceptionally generous mentor who provides encouragement and advice and shares ideas with former students and postdocs long after they leave his laboratory."

Barany even manages to bring his family into the scientific mix. His brother Francis is a professor of microbiology at the Sanford Weill Medical College of Cornell University, and in 1999 they published a paper on a new type of DNA microchip. It combines polymerase chain reaction/ligase detection reaction techniques with "zip-code" hybridization to help identify mutations in genes that regulate cell growth and differentiation.

And perhaps the ultimate in multigenerational research was a 2005 paper first-authored by his teenage son Michael and coauthored by Merrifield, Barany, and a former student, Robert P. Hammer, now a professor at Louisiana State University. Hashed out by father and son on summertime tandem bicycle rides between home and lab, the paper lays out a new method for synthesis of dithiasuccinoylamines. It's work that takes Barany back to his own early days as a chemist.

The award address will be presented before the Division of Organic Chemistry.—Michael McCoy

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter