Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Careers

Women Faculty Gain Little Ground

C&EN's annual survey shows that women top out at 25% of chemistry faculty at only two of top 50 schools

by Corinne A. Marasco

December 18, 2006

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 84, Issue 51

Despite an increase in the number who choose careers in science and engineering, women continue to be significantly underrepresented among university chemistry faculty. For the seventh year in a row that C&EN has examined this topic, the number of women among full professors and among chemistry faculty as a whole remains low. Nevertheless, the data do reveal slow progress between the 2000-01 and 2006-07 academic years.

C&EN surveyed schools identified by the National Science Foundation (NSF) as having spent the most money on total and federally funded research in chemistry during fiscal-year 2004, the latest year for which data are available (www.nsf.gov/statistics/nsf06323). The schools were contacted by e-mail and telephone and were asked to provide the number of male and female tenured and tenure-track faculty holding full, associate, and assistant professorships with at least 50% of their salaries paid by the chemistry department in the 2006-07 academic year. These numbers exclude emeritus professors, instructors, and lecturers, as well as any faculty and endowed professors whose salaries are not paid by the chemistry department. The response rate was 100%.

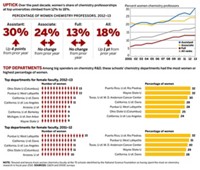

In academic year 2006-07, women represent 14% of the total chemistry faculty members at the top 50 institutions. Although this number is low, it represents a slight improvement compared with data from prior years: 13% in 2005-06 (C&EN, Oct. 31, 2005, page 38), 12% in 2004-05 (C&EN, Sept. 27, 2004, page 32), and 12% in 2003-04 (C&EN, Oct. 27, 2003, page 58). The first time C&EN carried out this survey, 2000-01, women made up just 10% (C&EN, Oct. 1, 2001, page 98). In absolute terms, the total number of faculty positions increased from 1,633 last year to 1,672, and the total number of positions filled by women increased from 213 to 226.

The makeup of the list of top 50 schools varies little from year to year. The University of California, San Francisco, which has been ranked first on the NSF list since 2000 in terms of spending on chemical research, maintains its number one position this year. Schools added to the list in 2006 are the University of Chicago and the University of Virginia. Schools that were on the list in 2005 but dropped off in 2006 are the University of Oklahoma and Emory University. Together, those schools had five female chemistry faculty members, whereas the schools that replaced them have four.

Among the schools that have the highest proportion of women in the total faculty, Rutgers University and the University of California, Los Angeles, are tied for first place, with women accounting for 25% of the chemistry faculty this year. There is a three-way tie for second among Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Pennsylvania State University, and Purdue University, where women make up 21% of the faculty. In third place is the University of Arizona, where women make up 20% of the faculty.

At the other end of the spectrum, all of the institutions on the list this year have more than one woman on faculty. But six of the top 50 have no women full professors.

Women continue to be concentrated in the assistant and associate professor ranks. This academic year, women make up 21% of assistant professors, the same as last year. Women's representation among associate professors is 22%, up from last year's 21%. Women increased their share among full professors this year, to 10% from 9% last year. Looking back to the 2000 baseline, the proportion of women full professors has increased at a glacial pace, as has their share of total faculty. The proportion of women in the associate and assistant professor ranks has varied little over the years, hovering near 21% in recent years.

In an effort to pin down the reason that women aren't making the leap to full professor, economists Donna K. Ginther of the University of Kansas and Shulamit Kahn of Boston University recently examined how gender differences affect the likelihood of obtaining a tenure-track job, promotion to tenure, and promotion to full professor in the life sciences, physical sciences, and engineering. Ginther and Kahn approached the question by analyzing data from NSF's 1973-2001 Survey of Doctorate Recipients. They presented their findings in a paper published by the National Bureau of Economic Research, titled "Does Science Promote Women? Evidence from Academia 1973-2001" (www.nber.org/~sewp/Ginther_Kahn_revised8-06.pdf).

In brief, Ginther and Kahn conclude that women are less likely than men to hold tenure-track positions in science and that the gap is entirely explained by the decision to have children. Furthermore, the authors report no gender difference in promotion to tenure or full professor after controlling for factors such as demographics and employer characteristics. They also found that family characteristics have different effects on the likelihood of promotion for men and women: "Children make it less likely that women in science will advance up the academic job ladder beyond their early post-doctorate years," whereas both marriage and children are positively correlated with men's likelihood of advancing. The results back the conventional wisdom that women often must choose between a family and an academic career.

Other studies have found that women with young children spend less time in the lab than their male counterparts do, presumably because they shoulder the responsibilities of child care. Also, the model of academia as the most desirable place for a research career may lead to a mismatch between expectations and outcomes, leading women to seek nonacademic careers that are family-friendly.

Read More

- Table 1: Women In Academia

- Among the top 50 universities, women held the greatest share of chemistry professorships at Rutgers University and UCLA

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter