Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Materials

Ancient Steel's Surprise Ingredient

Damascus saber is found to contain carbon nanotubes

by Bethany Halford

November 16, 2006

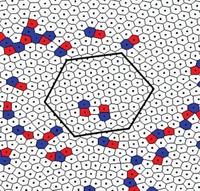

Western Europeans first learned of Damascus steel's remarkable properties during the Crusades, when they encountered the ultra-high-carbon material of the swords and daggers carried into battle by their Muslim adversaries. They gravely noted the steel's strength and unparalleled sharpness—legend has it that a Damascus steel blade could slice through a silk handkerchief floating in midair. What they didn't know was that the steel had been enhanced with carbon nanotubes.

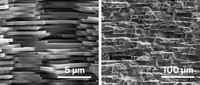

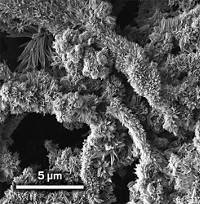

A team led by Peter Paufler, a physicist at Germany's Technical University of Dresden, recently made that discovery when the researchers found multiwalled carbon nanotubes (MWNTs) in steel from a 17th-century Damascus saber (Nature 2006, 444, 286). The researchers spied the 400-year-old nanotubes, possibly the oldest manmade MWNTs on record, while using high-resolution transmission electron microscopy to investigate the blade.

Others have studied Damascus steel's microstructure, but only after Paufler and coworkers dissolved the material in hydrochloric acid were they able to see the MWNTs. They also found incompletely dissolved Fe3C nanowires, "indicating that these wires could have been encapsulated and protected by the carbon nanotubes," they note.

European metallurgists were never able to replicate Damascus steel, and the ancient recipe has been lost for nearly 200 years. Paufler hopes that the nanoscale structures will offer insight into that recipe and provide clues as to how the metal's unusual banding pattern forms. "As the nanoscale structure of Damascus steel emerges, a refined interpretation of its remarkable mechanical properties should become possible," the researchers say.

John Verhoeven, an emeritus professor of materials science at Iowa State University who has studied samples from the same blade, isn't so sure. He tells C&EN that he would expect the same nanostructures to occur in pearlite, a ubiquitous component of steel. "I doubt that they play any role in the unique banded microstructure that gives Damascus steels their beautiful surface patterns," he says. "However, further research would be needed to decide this question."

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter