Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Analytical Chemistry

What’s that Stuff

What's that stuff? Amber

Fossilized resin from trees is prized for its use in jewelry and science

by Michael Freemantle

March 12, 2007

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 85, Issue 11

In January, I bought a piece of Baltic amber in Camden Passage, a street in north London renowned for shops that sell antiques, jewelry, and art products. "How do I know the amber is genuine?" I asked the seller. "It comes from a reliable source," she told me. "And if you look closely, you'll see it contains a fly."

Amber might be the only product in the world that increases in value when it contains flies. Yet even fake amber may have embedded insects.

There is no simple nondestructive test to distinguish between genuine and fake amber, according to amber expert Ken B. Anderson, associate professor of organic geochemistry at Southern Illinois University, Carbondale. "The only definitive tests involve spectroscopy or other types of analysis that are beyond the scope of most people buying amber," he says. "In my experience, most barren amber sold for jewelry is genuine. On the other hand, because of the increased value, it is fairly common to find fakes with inclusions."

Amber is a yellow transparent or translucent fossilized material formed from resin that oozed from trees many thousands or millions of years ago. It is sometimes tinted red, orange, or brown, and may be clouded by minuscule air bubbles. Trees exude resin for many reasons, among them to combat disease, seal wounds, and prevent attack by insects. The material is initially sticky, but on exposure to light and air, most resins tend to harden into solid masses that are resistant to normal decay processes. Pieces of amber often survive, buried in soils or sediments, for millions of years, yielding invaluable scientific information about the history of life on Earth.

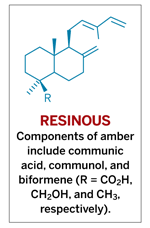

Natural resins such as amber generally consist of mixtures of organic compounds, including alcohols, ketones, carboxylic acids, and most notably, unsaturated hydrocarbons known as terpenes and related terpenoid compounds. Monoterpenes, isomers with the formula C10H16, consist of two isoprene units [CH2=C(CH3)CH=CH2]. The majority of resins consist mainly of compounds based on diterpenes, C20H32.

The most common type of amber contains members of a diterpenoid family known as labdanoids. These components readily polymerize to form macromolecular compounds.

"Resins that do not form polymers tend to be soft and are less able to survive the physical attrition that occurs when they are buried in sediments," Anderson says. "In most cases, ambers contain a macromolecular phase within which nonpolymerizable components become trapped. The polymerizable components in ambers tend to be fairly consistent across many species and throughout geologic time."

The nonpolymerizable components in amber often are characteristic of the vegetation that existed at a particular place and time. "Even when natural decay processes have altered other types of plant tissues to a degree where their taxonomic value as fossils is limited, ambers persist and preserve in their structure and composition a record of their own origins," Anderson explains.

The fossilized resin is found throughout the world, although much of the amber used for jewelry derives from deposits in Europe's Baltic region and from the Dominican Republic. Most ambers are 20 million to 130 million years old. However, recognizable ambers have been discovered that originated around 240 million years ago.

Because amber is an organic material, its age can be determined by carbon-14 radioisotope dating, but only if the sample is less than about 40,000 years old. The age of much older ambers can be inferred from the age of the surrounding sediments. Radioisotopes with half-lives much longer than that of 14C are used to date the sediments.

Amber has a fascinating history of "medicinal" applications. The Greek physician Hippocrates, who lived around 460–377 B.C. and is often called the father of medicine, used a mixture of crushed amber and honey to treat "dimming eyesight." And the German religious reformer Martin Luther (1483–1546) carried amber for protection against kidney stones.

Because amber is easy to cut, it also has been used to make candlestick holders, chess pieces, and other items, particularly ornaments. A spectacular example of its decorative use is the Amber Room in the Ekaterininsky Palace near St. Petersburg, Russia. The contents of the original room were lost in World War II. The present room is a reproduction based on old photographs.

Nowadays, amber is most commonly used to make jewelry. Because of its value, particularly when it contains the remains of insects or plants, some people have used a variety of materials to imitate amber. These materials include glass, phenolic resin, casein, a semifossilized resin known as copal, and synthetic plastics such as celluloid.

"Only copal and modern plastics are used to embed fake inclusions," notes Andrew Ross, curator of fossil arthropods at the Natural History Museum, London, in his book "Amber: The Natural Time Capsule." "If some of the insects are only a couple of millimeters long, then the pieces are likely to be genuine," he notes.

Anderson observes that pieces of amber containing insects that are beautifully laid out are likely to be fake. Insects generally struggle to free themselves when stuck in amber and therefore end up in odd positions, he explains.

I looked at my recently purchased piece of amber again, this time using a magnifying glass. The fly is longer than 2 mm, but it's difficult to tell if it struggled before being "ambalmed." So I'm still wondering: Is the piece genuine, or is it a fake?

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter