Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Environment

Pesticides Block Chemical Communication In Crops

Soil contaminants may inhibit symbiotic nitrogen fixation by plants

by Sarah Everts

June 11, 2007

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 85, Issue 24

Some pesticides and soil contaminants seem to block the symbiotic relationship between alfalfa and nitrogen-fixing bacteria, according to a new study. The finding could have significant impacts on the agriculture industry.

When synthetic chemicals compromise symbiotic nitrogen fixation, the environmental consequences include increased dependence on synthetic nitrogenous fertilizer, reduced soil fertility, and declining crop yields, says study author John A. McLachlan, director of the Center for Bioenvironmental Research at Tulane University (Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007,104, 10282).

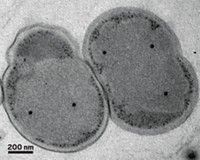

Normally, when legumes such as alfalfa can't find a usable source of nitrogen in the soil, they respond to chemical signals produced by soil bacteria such as Rhizobium and begin to produce nodules on their roots. These nodules provide shelter for the bacteria while they turn N2 gas into ammonia that the legume can use.

McLachlan and his colleagues studied how five typical endocrine disrupters block this microbe-to-plant communication in alfalfa. They found that terminating that chemical "chatter" leads to reduced plant yield.

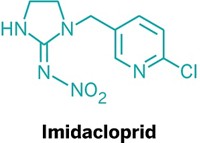

The researchers evaluated bisphenol A, used in the plastics industry and a typical soil contaminant; methyl parathion, an insecticide; chrysin, a clover-derived phytochemical; pentachlorophenol (PCP), an insecticide and wood preservative whose use has recently been restricted in the U.S.; and DDT, an insecticide still used widely in developing nations but banned in the U.S.

"This research brings up an interesting idea, that such soil contaminants might interfere with nitrogen fixation, but it needs to be tested under more realistic conditions," comments Michael Sadowsky, a soil microbiologist at the University of Minnesota.

Rather than assuming that the findings apply to all N2-fixing bacteria, Sadowsky and others would like to see more concentrations of the soil contaminants evaluated, different legume-bacteria relationships tested, and the research reproduced in a field setting. McLachlan says follow-up studies such as these are currently in progress in his research group.

The Rhizobium-legume symbiosis shows potential as a diagnostic for soil pollution, says Dietrich Werner, a plant biologist at the University of Marburg, in Germany. He bases this conclusion on his studies of the impact of cadmium and fluoranthene on N2 fixation.

Soil contaminants might affect other symbiotic relationships, Werner adds, such as arbuscular mycorrhizas, which are symbiotic fungi that solubilize essential minerals such as phosphate for most legumes, cereals, and even potatoes. The manner in which pesticides interfere with several plant symbioses should be studied, Werner notes.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter