Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Biological Chemistry

Remember This

by Rudy M. Baum, Editor-in-chief

September 3, 2007

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 85, Issue 36

A futurist, whose name I don't remember, delivered the plenary lecture at the Informex conference a few years ago. His presentation wasn't to my taste—he was too razzle-dazzle, too much the huckster.

One point he made during his presentation, however, stayed with me. As was appropriate for a talk to custom chemical manufacturers, the futurist was talking about future pharmaceutical opportunities. He pointed out that millions of people have Alzheimer's disease and, as the population of the U.S. and other Western nations ages, millions more will develop it. And he asked, "If you had a drug that could prevent the memory loss associated with Alzheimer's disease, how much would you pay for it?" I felt a little chill, because like every person in the packed ballroom, I knew the answer instantly. "That's right," he said, "you'd pay anything for that drug."

I was, perhaps, particularly sensitized to the futurist's message that evening because my mother was then in the early stages of the dementia that would rob her of any recognition of her family and friends and then take her life. My mother spent the last eight months of her life in the Alzheimer's units of two assisted living facilities in New Jersey and New York. I wasn't able to visit her regularly, but when I did, it was hard to watch her and the other residents who would never again connect coherently to an external reality, and would never again recognize their spouses, children, or friends.

This week's two-story cover package by Senior Editor Sophie Rovner focuses on the chemical underpinnings of memory and development of pharmaceuticals that can affect memory. Three other stories written by Rovner on specific aspects of memory appear as exclusives on C&EN Online.

"When was the last time you misplaced your car in a parking lot?" Rovner writes. "Gave you a bit of a scare, didn't it? What about when you blanked on the name of a longtime friend—did you wonder if you were showing the first signs of Alzheimer's?

"These are not trivial fears. Memory is as vital to your trip to the grocery story as it is to your role at work and to your very personality."

In the first story, "Hold That Thought," Rovner lays out current thinking about how short- and long-term memories are formed and stored in the brain. It is a staggeringly complex process, one that we are only at the early stages of understanding.

What does seem clear is that a long-term memory "is distributed over a network of neurons whose connections have been reinforced through long-term potentiation and growth of additional synapses," Rovner writes. "The memory can be recalled when the network is reactivated, though very little is known about this process."

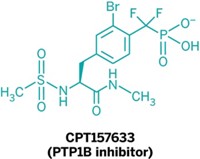

In her second story, "Memory Enhancement," Rovner surveys efforts by companies to develop drugs to halt the severe loss of memory associated with diseases like Alzheimer's, as well as the more common subtle deterioration of memory that is a normal process of aging.

A drug that could slow the loss of memory or even restore the memory of an Alzheimer's patient seems highly desirable. As Rovner writes, however, drugs to enhance memory are not without their detractors. For people who are not suffering dementia, the Food & Drug Administration considers such pharmaceuticals "lifestyle" drugs and is unenthusiastic about approving them.

The question lingers, however: Is improved memory an unalloyed good? For an Alzheimer's patient, surely the answer is a resounding "yes."

That said, in one of Rovner's C&EN Online exclusives, "The Well-Endowed Mind," she points to research that indicates that knocking out the gene for the enzyme cyclin-dependent kinase 5 enhances memory performance in mice. Reducing the activity of another protein that suppresses the activity of the transcription factor CREB has a similar effect. Such results suggest some sort of memory homeostasis mechanism.

Might it be that there is a selective advantage to having a good memory, but not too good a memory? Is forgetting important? Will drugs that improve memory in normal people have negative side effects? Fascinating questions.

Thanks for reading.

Views expressed on this page are those of the author and not necessarily those of ACS.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter