Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Business

DuPont Finds Itself

Company says it has completed a transformation from chemical maker to science firm

by Alexander H. Tullo

October 8, 2007

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 85, Issue 41

LAST MONTH, DuPont hosted journalists from around the world at its eminent Experimental Station in Wilmington, Del. Companies usually hold such events to show off a new corporate identity or a major acquisition. Sometimes the excuse is an anniversary, as in 2002, when DuPont held its last major press conference to commemorate its bicentennial.

This time around the reason is a bit more subtle. DuPont believes that a gradual transformation, a decade in the making, is now falling into place.

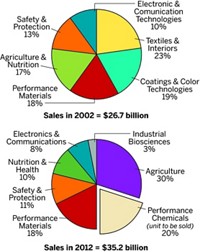

If measured by merger and acquisition activity, the amount of change has been immense. From 1997 to 2004, the value of all of DuPont's divestitures, acquisitions, and new joint ventures totaled $60 billion, more than twice the company's 2006 sales of $27.4 billion.

The theme of the transactions was getting out of cyclical commodity businesses and getting stronger in growing, technology-driven ones. Prominent divestitures included the oil company Conoco and the Invista fibers unit. Noteworthy acquisitions included the seed firm Pioneer Hi-Bred International and electronic chemicals maker ChemFirst.

Charles O. Holliday Jr., DuPont's chairman and chief executive officer, told reporters that the scheme is working. He pointed out in his presentation that the company is bigger now than it was in 2001, before the sale of Invista, which, at the time, represented about 20% of the company's $25 billion in sales. He attributes the subsequent sales increase to strong growth in its remaining businesses.

Those businesses include safety and protection, which makes products such as Kevlar; electronic materials; coatings and pigments; performance materials, including engineering plastics; and agriculture and nutrition, which houses the Pioneer seed business.

Holliday acknowledged that DuPont is not as big as it would have been without the divestitures. The company was the world's second-largest chemical company in 2001, behind Dow Chemical. By 2006, it had slipped to number six (C&EN, July 23, page 13).

But Holliday shuns such rankings. "People measure the worth of a company in many ways," he said. "One can just be the revenue turnover. We made the decision a decade ago that that was not the most important measure. It would be easy just to increase revenue turnover. We want to talk about value created."

And DuPont doesn't even consider itself a chemical company. Executive Vice President Ellen J. Kullman stated that DuPont's core business is "innovation and science." When asked by reporters what firms DuPont considers its corporate peers, Jeff L. Keefer, the firm's chief financial officer, mentioned 3M and Monsanto and even agreed with a comparison to industrial conglomerate United Technologies. "There are elements of our portfolio that are chemical-related, but we do not have the heavy-duty, ethylene-based petrochemicals that are really the backbone of Dow and BASF," he said.

Holliday's vision is for DuPont "to be the world's most dynamic science company." He said this means responding to customer needs "faster and better" than the competition does.

Another element of the vision is "sustainable solutions," which Holliday believes customers will increasingly demand. "We are in a resource-constrained world," he said.

Many of the technologies DuPont is developing address this constraint. The company is the largest supplier of materials other than polysilicon for photovoltaic cells, a market it says is growing 30% annually.

But the leading example of its sustainability efforts is probably biomaterials and biofuels. Earlier this year, DuPont started up a plant in Loudon, Tenn., with partner Tate & Lyle to make 1,3-propanediol from cornstarch.

That effort has led to work on biofuels. The company is developing a cellulosic route to ethanol with partners Novozymes and ethanol maker Poet. It also has a project with BP to make biobutanol. "We hitched our wagon to what we think are two new pieces of the biofuel equation, cellulosic ethanol and biobutanol," Holliday said.

Conventional bioethanol is made by fermenting corn-kernel-derived glucose into ethanol. In DuPont's cellulosic ethanol program, enzymes will break down corn stover, the leftovers of the corn harvest, into the sugars glucose and xylose. DuPont is developing a genetically modified Zymomonas mobilis organism, native to the agave plant from which tequila is extracted, to convert these sugars into ethanol.

"The cellulosic route to ethanol is a win-win," Holliday asserted. "We are taking a product that would just be plowed back into the field and has some value being plowed back into the field, but by properly collecting it and transforming it, we can increase the ethanol per acre." If only half the corn stover is processed, the amount of ethanol produced per acre can reach about 545 gal, the company says. Using only the kernels, an acre yields about 390 gal.

But DuPont says ethanol has its limitations as a fuel. It only has 66% of the energy content of gasoline, it is difficult to blend with other gasoline components, and it absorbs water. Butanol outperforms ethanol in all of these categories. BP and DuPont are building a biobutanol pilot facility in the U.K. and will eventually convert an ethanol plant to make the fuel.

The company says it also contributes to biofuels by developing seeds that boost agricultural production. The seed business has been problematic for DuPont, analysts say, but Citigroup's P.J. Juvekar says the company is turning it around with the introduction of new genetically modified seeds and better marketing. "DuPont, after losing market share to Monsanto for five years, seems to have kicked its efforts into high gear," he wrote in a recent report.

AMID THE CHANGE, the company says it isn't neglecting its more traditional businesses. For example, DuPont will spend $500 million to expand capacity for its Kevlar aramid fiber by 25% over the next three years. Kullman pointed out that there is more to Kevlar than bullet-proof vests. "The application you hear about the most is military," she said. But she notes that most of the growth the company is seeing in the product is in applications such as making lighter weight aircraft.

Another element of the transformation has been a change in how R&D is conducted. "We had focused on great research and less on the application," Holliday said. "We moved much more toward focusing on what the customer wants to buy and understanding the customer's needs and then internally putting the biologists and chemists together to find the answer." An example of the new approach is a new "innovation center," being constructed at the Experimental Station, that will house R&D and marketing personnel at the same location for the first time.

Thomas M. Connelly Jr., DuPont's chief innovation officer, explained that a "market back" approach yields better results than the "technology push" approach. "We can't leave our science in the laboratory," he said.

More transformation may be in DuPont's future. Keefer said the company may consider making big acquisitions again after a three-year hiatus. Cheap debt fueled a flurry of leveraged buyouts in the chemical industry, he explained, and made acquisitions too expensive for corporate buyers, but the recent tightening in the credit market puts DuPont in a better position. "There could be buying opportunities out there," Keefer said.

Although DuPont revealed much at the press event, it stayed mum on when the architect of its transformation will be ready to retire. Holliday has served as DuPont's CEO since early 1998, making him one of the longest tenured heads of a major chemical company. "Our mandatory retirement age is 65," he said. "I'm 59. I think we have a number of leaders who can be CEO tomorrow quite successfully. But I'm having too much fun to let them do it just yet."

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter