Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Chemical Sensing

Why Ladybugs Smell Bad

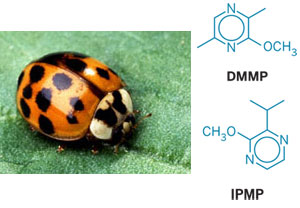

Methoxypyrazines are responsible for the odor released by spooked bugs

by Sophie L. Rovner

March 26, 2007

"Ladybird, ladybird, fly away home ..."—but not my home, if you please. Also known as ladybugs and lady beetles, these critters bedevil homeowners by emitting a stinky and lingering odor when disturbed or squashed. The same odor can ruin wine if the bugs settle in a vineyard and are processed along with the grapes.

Iowa State University researchers have now completed an exhaustive study of the chemicals responsible for the characteristic smell of the bugs' noxious emissions. The finding, which was presented yesterday at the American Chemical Society national meeting in Chicago, could lead to new strategies to eliminate the offensive compounds and improve wine quality.

Jacek A. Koziel, an agricultural engineer, took up the project as a change of pace from his usual work analyzing livestock odor (C&EN, Sept. 25, 2006, page 104). "I wanted to work with something different, with a different odor profile, something that many people could easily identify with," he told C&EN. "Since there were hundreds of lady beetles in my old office with leaky windows, I chose them. They released this characteristic odor when I handled them or when in my frustration I tried to swat them."

He enlisted his postdoc Lingshuang Cai as well as Iowa State entomologist Matthew E. O'Neal, a ladybug expert, to work on the project. Cai presented the team's findings before the Division of Agrochemicals.

The team studied the multicolored Asian ladybird beetle, which invaded the U.S. early last decade. Homeowners encounter the bugs because they aggregate inside buildings for shelter during winter, Cai noted. Wine growers cross paths with them when the bugs feast on damaged grapes in vineyards.

Because humans' odor detection threshold for the odiferous ladybug compounds is so low, "even a tiny amount in the wine will cause a great sensory impact on human tasting," Cai said. "That's why these compounds are so noxious."

The extent of the resulting wine taint problem is unclear, Koziel noted. But "there have been reports of vineyards going bankrupt because entire vintages were lost due to this problem."

Cai began the project by placing ladybugs in a capped glass vial for a day and then collecting the volatile compounds they released. She used gas chromatography and mass spectrometry to separate and identify individual compounds in the mixture. Then, a panel of human "sniffers" told her which of those compounds were the most important contributors to the ladybug scent. Of the 38 compounds identified, Cai determined that 2,5-dimethyl-3-methoxypyrazine (DMMP), 2-isopropyl-3-methoxypyrazine (IPMP), 2-sec-butyl-3-methoxypyrazine, and 2-isobutyl-3-methoxypyrazine play a major role.

The overall smell is a mixture of nutlike, green bell pepper, potato, and moldy odors. At the concentrations present in ladybug emissions, the mixture is "really stinky," Cai said.

The Iowa State researchers are not the first to assess ladybug emissions. But Cai noted that they were the first to discover that DMMP is an important contributor to the odor. "This study also provided the first unambiguous evidence that IPMP is responsible for the characteristic odor of live" ladybugs, Cai said. Koziel added that "we also are the first to observe a correlation between the color of the beetles and the amount of methoxypyrazine found in the air about them." Orange beetles release more of the compounds than do yellow beetles.

The Iowa State team's process also represents a "very sensitive, accurate method for identifying the presence of these compounds," Koziel noted. "This method will help those studying ways to prevent methoxypyrazines from contaminating wine." The group recently published details of its findings online in the Journal of Chromatography A (DOI: 10.1016/j.chroma.2007.02.044).

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter