Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Biological Chemistry

Sugary Site Of Malarial Invasion

Glycosaminoglycans are critical for transmission of disease through mosquitoes

by Carmen Drahl

September 17, 2007

Malaria parasites infect mosquitoes by clutching onto a newly identified sugar chain in the insects??? guts. This revelation could facilitate the development of new strategies to thwart transmission of the deadly mosquito-borne disease to humans.

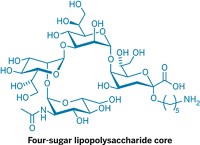

Sugar chains called glycosaminoglycans line human livers and mediate malarial infection. Now, independent teams led by molecular geneticist Marcelo Jacobs-Lorena at Johns Hopkins Malaria Research Institute and glycochemist Robert J. Linhardt at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute reveal that these chains also line mosquito guts (Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0706340104 and J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 25376). Jacobs-Lorena???s team also shows that blocking glycosaminoglycan production in mosquitoes prevents parasites from taking hold.

Neither study reports the complete sequence for the mosquito glycosaminoglycans, which are typically made of repeating two-sugar units decorated with negatively charged sulfate groups. Linhardt???s findings provide direct evidence for the presence of two specific two-sugar units. However, both the precise pattern of units and the chain length remain unclear, says Rhoel R. Dinglasan, a glycobiologist and lead author on Jacobs-Lorena???s team. Dinglasan and Jacobs-Lorena plan to collaborate with mass spectrometry experts to pin down the structure.

Diseased mosquitoes inject parasite-laden saliva into human hosts??? bloodstreams. Blocking the parasite???s attachment points to mosquitoes could cut off the parasite???s development, thereby preventing transmission to additional people. Malaria specialist Thomas J. Templeton at Weill Cornell Medical College notes that any potential therapies based on this science wouldn???t alleviate malaria symptoms in infected people. Such therapies would be community-based, and "you would need widespread coverage to be effective in reducing disease spread," he says.

"Malaria is one of the biggest killers in the world," Linhardt says. "New approaches, particularly ones targeting the infection in mosquitoes, are critical," he adds.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter