Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Business

The Acid Touch

Rising prices for sulfuric acid have widespread industrial impact

by Michael McCoy

April 14, 2008

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 86, Issue 15

Sulfuric acid is one of those unheralded lubricants that keep the gears of the industrial economy spinning. Although less in the limelight than petrochemicals such as ethylene or polyethylene, it is in fact the largest volume chemical in the world. Over the past six months, it has become a very expensive chemical as well.

The spot market price for sulfuric acid sold on the U.S. Gulf Coast is four times higher today than it was a year ago. And because sulfuric acid is critical to so many manufacturing operations, the price run-up is causing grief for a wide range of industrial users.

The story of sulfuric acid's rise is intertwined with the stories of metals, fertilizers, grains, and other commodities that have been skyrocketing in price in recent months because of insatiable demand from China and other developing countries. Although industry observers advance various explanations for why acid prices are rising, they all agree that some kind of market hysteria is also at work.

Robert Boyd, founder of the sulfur and sulfuric acid consulting firm PentaSul, traces the run-up back to what at the time must have seemed like an inconsequential hiccup: the inability of the Phoenix-based copper company Southern Copper to get a Peruvian sulfuric acid plant up and running on time.

Smelters of copper, nickel, and other metals play a pivotal role in the sulfuric acid business. Traditional refining of sulfidic copper ores creates copious amounts of sulfur dioxide gas, which most modern smelters capture and convert into sulfuric acid. Yet refining copper via the comparatively new solvent extraction/electrowinning technique requires huge quantities of sulfuric acid to leach metal out of copper oxide-rich ores. Depending on their location, metal companies can be big acid sellers or big acid buyers.

Early last year, Southern was set to become a big acid seller following the installation of abatement equipment designed to capture more than 92% of the company's sulfur dioxide emissions in the form of 1 million metric tons of sulfuric acid annually. However, Boyd says the plant didn't get fully going until May. In the meantime, Southern was forced to buy sulfuric acid on the open market to satisfy the customers it had lined up.

That open market, however, was becoming crowded with producers of metals and fertilizers seeking sulfuric acid for their own operations. Prices for these commodities were hitting all-time highs, and sellers were desperate to cash in while they could.

Since the initial market tightening last spring, the situation has only intensified. "I have never seen anything like it, and I have been in the business for 23 years," says Jack Weaverling, senior vice president of the Texas-based sulfuric acid marketer Shrieve Chemical.

Part of the problem, Weaverling and other industry players say, is the way that disparate events are converging to drive up the price of sulfuric acid.

These days, metal makers have an incentive to turn out as much copper as they can. According to the London Metal Exchange, copper is selling for more than $3.80 per lb today, compared with only about $1.40 at the beginning of 2005. Many firms are turning to the solvent extraction method and need acid to run these facilities. For example, at the same time that Southern is capturing and selling acid at its new Peruvian operation, the company plans to build another copper facility in Peru that will consume more than two-thirds of that acid.

Even crazier than metals is the phosphate fertilizer market, thanks to booming global demand for corn and other foodstuffs. A World Bank report puts the average 2006 price of diammonium phosphate (DAP), the most widely traded phosphate fertilizer, at $260 per metric ton on the U.S Gulf Coast. Last month, according to PentaSul, DAP broke $1,000 per metric ton.

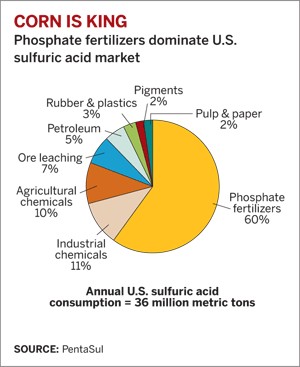

U.S. phosphate fertilizer producers use sulfuric acid to convert phosphate rock, mined chiefly in central Florida, into phosphoric acid. Their operations account for fully 60% of U.S. sulfuric acid consumption. Although most big fertilizer producers make their own acid, times of outsized demand can prompt them to look to outside supplies. And with the returns they are getting on DAP, they can afford to pay whatever the market is charging.

According to NorFalco, an Ohio-based company that markets sulfuric acid from several Canadian smelters and is one of North America's largest suppliers, fertilizer makers and other industrial firms can no longer count on the U.S. role as the world's dumping ground for excess acid. In a recent analysis, Kim Ross, NorFalco's director of market development, explains that U.S. buyers now have to compete with aggressive purchasers from metal and fertilizer companies around the world.

Even the Midwest ethanol boom is driving up demand for sulfuric acid. Ethanol is made from corn, and corn needs lots of fertilizer to grow. Moreover, ethanol plants themselves require sulfuric acid to manage the acidity of water used in corn processing, fermentation, and cooling. NorFalco calls ethanol the fastest growing U.S. outlet for sulfuric acid.

Some observers maintain that the problem isn't so much sulfuric acid as it is the acid's raw material, elemental sulfur. Although sulfur was once mined, today it is largely recovered from natural gas and oil-refining operations. For years, the amount recovered exceeded demand, and oil and gas companies were forced to store the mineral in huge piles. For most of this decade, sulfur was being delivered to Florida fertilizer companies for about $60 per long ton.

But the sulfur stockpile peaked in 2003, notes PentaSul's Boyd, and by 2005 the industry was drawing it down. Priced at less than $60 per long ton just a year ago, sulfur contracts in Tampa, Fla., had risen to $250 by first-quarter 2008, according to Boyd. Panicky buyers at Chinese fertilizer companies have paid as much as $600 per metric ton for delivered sulfur, although Boyd emphasizes that such spot market prices don't apply to companies that have long-term contracts.

Although not completely tied to sulfur, prices for sulfuric acid are following the raw material up. PentaSul's latest bulletin places the current Gulf Coast spot price for sulfuric acid at between $250 and $270 per metric ton, compared with about $60 at this time last year.

At Shrieve Chemical, Weaverling says sulfur producers are pushing for a price increase of between $150 and $240 per long ton for the second quarter of the year. Given that it takes about 1 ton of sulfur to make 3 tons of acid, sulfuric acid buyers could be looking at their own price increase of $80 per metric ton or even more.

These record price tags may be easy for metal refiners and fertilizer producers to swallow since their products are also fetching record prices, but they are not so palatable for purchasing managers at industrial chemical companies that use sulfuric acid in their operations.

Angie Copenhaver, global procurement strategist at specialty chemical giant Rohm and Haas, is such a buyer. "In the specialty chemical industry, there are some classes of raw materials that are ubiquitous," she says. "Sulfur and sulfur derivatives is one such group."

According to Copenhaver, Rohm and Haas consumes sulfuric acid at 18 of its manufacturing plants. For example, it takes 1 ton of sulfuric acid to produce 1 ton of boric acid, which Rohm and Haas uses to produce several key product families. Add in other sulfur derivatives and the impact runs throughout the company. "It hits all of our business groups," she says.

Rohm and Haas says it is unable to keep absorbing higher costs for sulfuric acid and other raw materials. One attempt to recoup them is an April 1 increase of anywhere from 4 to 8 cents per lb for polymers and additives used in coatings. Yet paint industry customers, already hit by the housing downturn, are in no mood to pay more for their raw materials, Copenhaver acknowledges.

Smaller companies are feeling sulfuric acid's bite as well. Graver Technologies is a Delaware-based producer of separation, purification, and filtration products. At its Newark, N.J., plant the company manufactures ion-exchange resins used by power companies and other industrial firms to remove contaminants from process and wastewaters.

Keith Platoff, purchasing manager at the Newark facility, says he has seen the price of sulfuric acid double over the past year to almost $200 per ton, and he's being warned about further price increases. The plant uses the acid mainly to regenerate ion-exchange resins and to neutralize wastewater before disposal.

Just as at Rohm and Haas, Graver can't easily pass on the higher costs to customers. "The ion-exchange market is very competitive," Platoff notes, "and we need to keep a lid on costs."

He says Graver has studied alternative acids and new sulfuric acid suppliers; still, a switch would have to be made with extreme care because Graver's customers depend on its ion-exchange resins to produce ultraclean water. Any reduction in water quality in a big power plant, Platoff notes, could cause irreparable damage to very expensive turbines and other power-plant systems.

At Rohm and Haas, Copenhaver points out that widespread switching away from sulfuric acid would entail prodigious amounts of R&D and reengineering. "If we believed this was going to continue on a long-term basis, we would look at switching," she says. "But I do believe this is a bubble."

Boyd, the consultant, agrees that current prices aren't supported by supply-and-demand economics and thinks they will come back down. Yet he cautions that it will be later rather than sooner. "In the long term, sulfur and sulfuric acid will be back in balance, but not before 2009," he says.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter