Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Business

Latin America

Chemical projects abound in the fast-growing region

by Alexander H. Tullo

January 14, 2008

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 86, Issue 2

LATIN AMERICA is experiencing its longest period of sustained growth in more than a generation. The region has benefited from strong export markets for commodity goods and generous foreign investment. In addition, shrewder government bureaucrats have nurtured domestic growth while tackling chronic ills such as high inflation. In such an environment, the wind is at the back of Latin America's chemical industry.

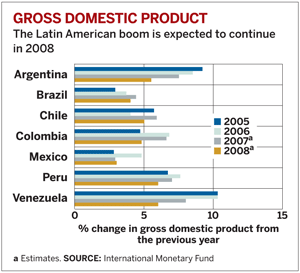

The International Monetary Fund projects that South America and Mexico together saw 4.9% gross domestic product growth in 2007. "Latin America's present expansion is its longest since the 1960s, and sustained growth has helped reduce external vulnerabilities," IMF said in a recent report.

But the fund cautioned that the region could see some spillover from an economic downturn in the U.S. or the world. Namely, it said, the financial crisis stemming from the U.S. subprime mortgage meltdown could reduce exports and tighten financial markets enough to slow investment. It projects regional growth to slow to 4.2% in 2008.

Brazil's largest chemical company, Braskem, says economic growth and greater disposable income pushed up the country's domestic consumption of thermoplastics by 5% in the first nine months of 2007. During the same period, the firm's sales increased by 10% to $7.0 billion while its earnings before taxes increased by 21% to $1.3 billion.

Oxiteno, a Brazilian firm that makes ethylene oxide and derivatives such as detergents, saw product volumes increase by 10% in the first three quarters of 2007. Sales, however, increased by only 4% to $619 million while earnings declined by 27% to $54.5 million. The company blamed the fall on rising ethylene costs and strength in Brazil's currency, the real, which hurt earnings from exports.

Last year, with the assistance of Petrobras, Brazil's state oil company, these two companies were involved in the largest consolidation in the history of the Brazilian chemical industry.

Two acquisitions involving Petrobras kicked it off. Along with Braskem and Oxiteno's parent company, Ultrapar, Petrobras purchased Brazilian refiner and polyolefins maker Ipiranga for about $4 billion. Ipiranga's $1 billion-per-year petrochemicals business went to Braskem and Petrobras, which split the assets 60-40, respectively.

Petrobras also purchased Suzano Petroqu??mica, the largest polypropylene producer in Latin America, for $1.4 billion. Suzano owns a 33% interest in Rio Polímeros, a new ethylene and polyethylene complex in the state of Rio de Janeiro, and has a 7% stake in Petroquímica União (PQU), a petrochemical complex in the state of São Paulo. Petrobras already had 17% stakes in those two plants.

These acquisitions set the stage for two subsequent deals. Petrobras and industrial group Unipar announced the formation of a new company, for now called Companhia Petroquímica do Sudeste, that will run some $3 billion in chemical assets held by the two. In the process, the new firm will gain control of PQU and Rio Polímeros. It will also own Suzano and the polyethylene maker Polietilenos União.

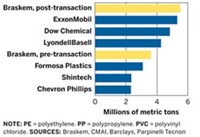

Petrobras made a similar deal with Braskem. It upped its holding in Braskem from 6.8% to 25.0%. In exchange for the stake, Petrobras is turning over its 37.3% holding in Copesul, a petrochemical complex in the southern Brazilian state of Rio Grande do Sul, giving Braskem full ownership. Braskem also got Petrobras' share of Ipiranga's petrochemical unit. Also going to Braskem is Petrobras' 40% stake in a polypropylene plant the two are building in São Paulo and Petrobras' low-density polyethylene maker, Petroquímica Triunfo.

To Braskem, the deal will yield synergies and help it toward its goal of becoming one of the 10 largest petrochemical companies in the world. In a conference call with analysts, José C. Grubisich, Braskem's chief executive officer, called the deal "the first step for growth and development for Braskem as a global competitor in this industry."

Jorge O. Bühler-Vidal, director of North Brunswick, N.J.-based Polyolefins Consulting, says the consolidation is needed to move the Brazilian chemical industry forward. Investment decisions are complex when chemical plants are owned by many entities with minority stakes. "It is easier to get two or three people to agree on something than 20," he says.

Bühler-Vidal says the consolidation will also help pave the way for Comperj, an $8.5 billion petrochemical complex planned for the state of Rio de Janeiro. The facility is envisioned as including an oil refinery and plants making a variety of basic petrochemicals. Likely partners include Petrobras, Ultrapar, and the newly formed Companhia Petroquímica do Sudeste.

Venezuela's government also has grandiose plans to expand its petrochemical sector. President Hugo Chávez Frías is a fan of the industry. "Petrochemicals are in everything that's important for life," he remarked last year.

Under Chávez' direction, state chemical maker Pequiven aims to become one of the world's 10 largest petrochemical companies. Pequiven's plan, dubbed "the socialist petrochemical revolution," calls for spending up to $15 billion by 2013 to execute 35 chemical projects. Pequiven says the program will almost triple its chemical output to 32 million tons per year.

The company already has a joint-venture agreement with Braskem for the first of several planned ethylene crackers: a $2.6 billion project set for 2012 in José, Venezuela. The two companies are also planning a $900 million polypropylene plant.

Colombia is getting into the act as well. Last month, Colombian state oil company Ecopetrol announced it would buy Propilco, Colombia's leading polypropylene firm, for $690 million. Propilco's 380,000 metric tons of capacity makes it a much bigger chemical player than the company buying it. Ecopetrol says the acquisition will give it the critical mass to pursue worldscale petrochemical projects in the country.

Peru is also seeing some activity. U.S.-based CF Industries is negotiating a deal with regional hydrocarbon firm Pluspetrol to build a nitrogen fertilizer plant in Peru based on local natural gas. Pluspetrol is also discussing an ethylene project there with foreign partners.

AS PROJECTS in the region multiply, Mexico's chemical sector keeps falling behind. Pemex, the state oil company, once had plans for a $1.9 billion ethylene cracker with private industry partners including Mexico's Grupo Idesa and Indelpro and Canada's Nova Chemicals. The project, known as Phoenix, was canceled. Pemex later proposed a scaled-down plan to expand two of its ethylene crackers to feed derivatives units built by the private industry partners. That project was also shelved. Now Pemex is only planning to expand an ethylene cracker to feed a polyethylene plant it built two years ago.

To Arturo Garcia, who left as supervisor of the Phoenix project to lead Mexican chemical distributor Química Delta, the turn of events is tragic. Blessed with hydrocarbons, Mexico could have a large petrochemical industry. Instead, it had an $8.4 billion deficit in chemicals in 2006, according to the country's chemical trade association. Pemex, however, was able to raise petrochemical production by 10.6% through the first nine months of 2007.

Garcia says petrochemicals aren't a high priority for the Mexican government. "The administration has decided they will not invest in petrochemicals," he says. "We truly believe this is not the right decision." He is mostly critical of the government's insistence on maintaining Pemex' crippling hydrocarbon monopoly rather than letting the oil company work with private industry to get projects completed. Even Venezuela, he notes, is open to private capital.

Some Mexican companies are still finding ways to grow. Last year, Grupo Alfa, which owns the polyethylene terephthalate maker DAK Americas, purchased Eastman Chemical's PET plants in Mexico and Argentina. Fluorine and polyvinyl chloride maker Mexichem purchased Colombian PVC maker Petroqu??mica Colombiana.

Given Pemex' problems, it makes sense to Bühler-Vidal that these Mexican companies are looking elsewhere in the region to expand their businesses. "The ones that want to grow are growing elsewhere," he says.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter