Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Policy

Numbers Shrink At Weapons Labs

Congressional budget cuts, downsizing hit scientists

by Jeff Johnson, Jyllian Kemsley

June 30, 2008

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 86, Issue 26

A CONTINUOUS reduction in congressional funding for U.S. nuclear weapons science is working its way through the Department of Energy's three weapons labs. For several years running, Congress has trimmed several hundred million dollars from the Administration's $6 billion-plus request for spending to maintain the U.S. nuclear weapons stockpile. The weapons spending makes up the lion's share of the $9 billion annual funding for the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA), the semiautonomous DOE agency that runs the country's nuclear weapons operation.

Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in Northern California has been hit the hardest. Livermore management is expected soon to announce the termination of jobs for up to 100 contract employees.

This reduction comes on top of layoffs in late May of 440 permanent career employees, including 164 lab scientists. This marks the first time that the lab has laid off permanent staff since 1973, Livermore spokeswoman Susan M. Houghton says.

In January, Livermore terminated 450 temporary contract employees. The lab also offered early retirement packages to permanent employees, 215 of whom took the offer, Houghton continues. Adding in normal attrition, contract completion, and retirements, Livermore will be down about 2,000 people from 2006 levels to a total workforce of about 6,600 people by July, she says.

The job cuts have been spread across the sciences, and Houghton could not say how many chemists were laid off. Layoff decisions were based not on seniority—110 of the scientists had been at the lab for more than 10 years—but on ability, she adds. The lab retained people with skills it deemed critical for future research programs. For instance, Livermore spared scientific staff affiliated with the National Ignition Facility, a new laser facility.

Along with the budget cuts, scientists at the three weapons labs—Livermore, Los Alamos National Laboratory, and Sandia National Laboratories—face a changing environment and an uncertain future. NNSA leaders have said the weapons budget will not grow in the future and the labs are moving to a more diversified research portfolio that includes a greater share of nonweapons work (C&EN, Nov. 19, 2007, page 12).

But Livermore lab officials stress that the current layoffs are due to budget constraints over the past several years and are not a result of NNSA's future plans. Livermore was hit by a $280 million shortfall in its $1.6 billion operating budget due to a double whammy of budget cuts and increased management fees, taxes, and benefits costs related to the recent shift in lab management from the nonprofit University of California to a consortium made up of private companies and UC.

"We believe that we are positioned correctly to avoid any future involuntary separations," Houghton says, although she leaves the door open to further staff reductions through attrition.

Similar staff and budget reductions are taking place at Los Alamos and Sandia.

SINCE 2006, Los Alamos has reduced its workforce by about 2,100 staff members, 46% of whom were technical, according to lab figures. It currently employs about 8,000 full-time staff and 3,000 contractors.

Last year, because of a basically flat budget and increasing costs, Los Alamos was forced to cut 500 staff through a "voluntary separation program," explains Kevin Roark, a Los Alamos spokesman. "These reductions, however, along with normal attrition, meant that we did not have to resort to a layoff," he says.

"All this is in the past," Roark continues. "We are not going to do a separation program again." Paralleling Houghton's picture for Livermore, Roark says Los Alamos is maintaining its workforce through normal attrition and "strategic hiring" and "is now in a good position to manage our workforce."

Sandia officials also note a drop in employees over the past few years. They say Sandia's overall workforce has declined by 477 positions since fiscal 2006 and project a drop in staff from approximately 8,400 full-time employees today to about 7,800 in 2010. This comes along with a reduction in the direct nuclear weapons workforce of 18% since 2004, Sandia Labs Director Thomas O. Hunter said, speaking to a Senate panel in April. Direct weapons work is now less than half of Sandia's budget.

Late last year, Sandia announced 110 positions would be eliminated over the months that followed, which they attributed to lab streamlining and a shift in needs within the lab. After attrition and transfers within the lab, however, the jobs of only 25 people were terminated.

Overall, NNSA is headed for significant change. In the next decade, NNSA Administrator Thomas P. D'Agostino has announced, the size of the nuclear weapons infrastructure will be reduced by 30% and the staff by 20 to 30%. The staff reduction, he said, will occur mostly through retirements and a shift from weapons work to nuclear nonproliferation programs and other nuclear-related but not nuclear weapons activities. The infrastructure reductions will include demolition of some 600 buildings and elimination of redundant activities at some labs (C&EN, Dec. 24, 2007, page 29).

D'Agostino's plan to downsize and streamline the labs will also reduce the number of nuclear weapons maintained by NNSA and could include developing a new nuclear weapon, the "reliable replacement warhead," which would be easier and cheaper to maintain and keep secure.

CONGRESS has been unwilling to fund the warhead, however, and has been lukewarm to the overall transformation plan. Late this month and for the second year in a row, the House Committee on Appropriations' Subcommittee on Energy & Water refused to fund a $10 million Bush Administration request to study the warhead.

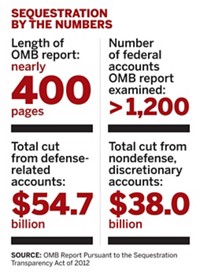

It is also likely congressional funding for the weapons labs will continue to decline. The appropriations subcommittee cut the Administration's request for fiscal 2009 by $400 million to $6.2 billion, which means a basically flat budget since 2006.

The layoffs, budget cuts, and shifts in funding are stressful and confusing for lab scientists, who worry about the loss of scientific capability at the labs and cuts to core lab programs.

"Morale is terrible," says Jeffrey D. Colvin, a physicist who works in Livermore's Chemistry, Materials, Earth & Life Sciences Directorate. "It's very depressing even for those of us not getting notices. We have to say good-bye to long-term colleagues." A 25-year lab veteran, Colvin survived the cuts in May.

Keith E. Grant was employed by Livermore for 36 years before he was laid off in May. A physicist who worked in atmospheric chemistry, he says a big part of why he stayed so long at the lab is because of the interesting work he was able to do there, but he worries about the lab's future.

"What I've seen over the last few years is what I call the growth of 'we can't do it unless you've got an explicit programmatic justification,' " Grant says. "It used to be 'sure, we'll do it unless there's a reason we shouldn't.' "

Grant notes that many research programs at Livermore seem to be in limbo.

"Right now, they haven't closed down programs and said 'we're definitely not going to do this.' But there isn't any real support for them, either," he says, adding that three weapons labs really need more direction from above. "I think for the labs, a lot of it boils down to Congress and DOE deciding what they really want to support and what the national labs should be as institutions," Grant says.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter