Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Environment

Tank Troubles

Report challenges data, scientific assumptions of DOE Hanford Waste Cleanup

by Jeff Johnson

July 21, 2008

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 86, Issue 29

THE CLEANUP of 56 million gal of radioactive and hazardous chemicals stored at the Hanford Site in eastern Washington state is shrouded in confusion and delay, according to report released in June by the Government Accountability Office (GAO).

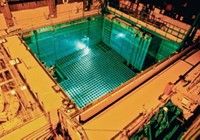

The liquid and semisolid wastes are contained in 149 single-shell and 28 double-shell underground tanks. Some 61 of the single-shell tanks have leaked, and as much as 1 million gal of liquid waste is now in the soil.

For more than a decade, the Department of Energy has been working to prevent further leakage and to eventually remove and treat the waste. Together with the Washington state government and the Environmental Protection Agency, DOE has developed a complex plan to vitrify the waste, that is, seal it in glass, and then place the solidified products in canisters for long-term deposit in an underground repository. However, no waste has been vitrified, and treatment of the waste is not likely to occur until 2019 or later. Removal and treatment may continue until 2050, the GAO report says.

The report warns that so much uncertainty surrounds DOE's basic knowledge of the tanks' contents that removal and treatment will be very difficult. The report is particularly concerned about the continued leakage of the single-shell tanks.

The tanks hold a complex mix of radioactive elements and chemicals, making determination of any one tank's constituents uncertain and emptying the tanks technically challenging. Among the contents are discarded equipment, plastic and metal bottles, and other junk, as well as chemical and radioactive waste. Nearly all, 98%, of the waste's radioactivity comes from strontium-90 and cesium-137, although more than 40 other radioactive elements are contained in the waste, GAO says.

The waste was generated between 1943 and 1989 as the U.S. produced plutonium in Hanford's nuclear reactors to make warheads for the U.S. nuclear weapons stockpile. The tanks are located on 18 tank farms on the 586-sq-mile reservation.

The older single-shell tanks were designed to last 10 to 20 years until a permanent waste storage site could be found, the report notes. But as early as 1948, concerns among scientists rose over the tanks' long-term viability, and leakage to soil was confirmed in 1961. From 1968 to 1986, 28 new tanks with double-carbon steel walls were constructed, allowing monitoring with cameras between the wall layers. Seven single-shell tanks have been emptied into double-shell tanks. The tanks vary in size: The oldest holds 55,000 gal and the newest has 1 million-plus-gal capacity.

IT'S VIRTUALLY IMPOSSIBLE to see inside of the single-shell tanks or to even monitor leakage internally, GAO says. Surface measurement devices are installed inside the tanks, and cameras can be lowered into the space above the waste, but the report says such measurements have been shown to be inaccurate. Instead, DOE has turned to groundwater monitoring wells that show when leaks occur; however, only leaks of 4,000 gal or more can be detected this way.

The report calls for more negotiations with state and federal regulators to develop realistic cleanup and removal schedules as well as to better assess the integrity of single-shell tanks and to better quantify the risk of their continued use.

DOE cleanup officials took issue with portions of the report. In a statement, Inés R. Triay, principal deputy assistant secretary in the DOE Office of Environmental Management, described the ongoing nature of the waste removal. She pointed to a 2006 National Academy of Sciences study that determined DOE's knowledge of tank waste was adequate for remediation efforts, but she noted that the same report recommended that characterization continue as waste is removed, particularly from the single-shell tanks.

Triay also said that DOE will continue to study the makeup of the waste as part of further negotiations with regulators to set new cleanup milestones.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter