Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Physical Chemistry

Messenger From Mercury

Exploration of the sun's closest neighbor begins anew after 20 years

by Elizabeth K. Wilson

February 18, 2008

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 86, Issue 7

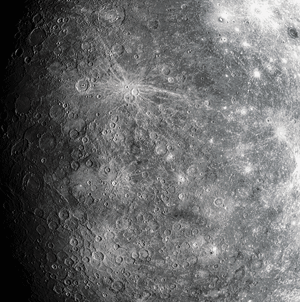

The Messenger spacecraft is sending back new images of dense, rocky Mercury, like this one of the planet's previously unseen side.

IT'S NOT THAT SCIENTISTS have been uninterested in Mercury; it's just been a tough commute. But now Mercury is finally getting some long-overdue attention as the first results from the Messenger spacecraft, which flew by the planet last month, are coming in.

The solar system's innermost planet has a magnetic field, possibly produced by a giant and mysterious core of molten iron; a volcanic past; a host of surface minerals that produce an exotic, tenuous atmosphere; and possible ice lurking in shadowed craters, even with day temperatures that would melt lead. But the planet's proximity to the sun's blistering heat and high-energy plasma breath spell peril for even the hardiest sensors and electronics. And the sun's powerful gravity dwarfs that of little Mercury, threatening to pull a visiting spacecraft into its fiery maw.

Consequently, despite an armada of robotic craft that planetary scientists have sent to Mars, Venus, Saturn, and Jupiter, Mercury has had only one visitor: the Mariner 10 spacecraft, which executed three quick flybys in 1974 and 1975.

Now it's Messenger's turn to get a look at Mercury. The craft is part of the Discovery program of fast, relatively cheap National Aeronautics & Space Administration missions. It sports recently developed protective technologies, such as sun shades of ceramic cloth and solar panels that work at high temperature.

"The science has been compelling for 20 years, but the mission became technologically feasible in the '90s," says Sean C. Solomon, planetary scientist at the Carnegie Institution of Washington (CIW), in Washington, D.C., and the mission's principal investigator.

A collaboration between NASA, Johns Hopkins University, and CIW, Messenger (which stands for MErcury Surface, Space ENvironment, GEochemistry, and Ranging) was launched in 2004 and is now in the midst of executing a lengthy and complex series of planetary flybys, including two more of Mercury in the next few years for gravitational assists before finally settling into a stable orbit in 2011.

At a recent press conference, scientists released images from the first flyby, including photos of the never-before-seen side of Mercury, deep craters in the planet's surface, and a giant crater beset with radial cracks dubbed the "spider."

Soon to come from that same flyby are results from Messenger's spectrometers, which study the chemistry of Mercury's surface and atmosphere. They are scheduled to be announced in a series of 23 talks presented on the first day of the 39th Lunar & Planetary Science Conference in League City, Texas, in mid-March.

Scientists are keeping mum about the information until they finish their analyses, but planetary scientist Ann L. Sprague, a Messenger mission team member at the University of Arizona, Tucson's Lunar & Planetary Laboratory and author of the book "Exploring Mercury: The Iron Planet," says the new data are "very exciting."

Messenger promises to help answer a number of questions. From the Mariner 10 flybys, scientists learned that Mercury has a magnetic field likely produced by a liquid outer core, but the source of the liquidity remains a mystery. Sulfur, or even oxygen, could allow this portion of the core to stay liquid or mushy, Sprague says.

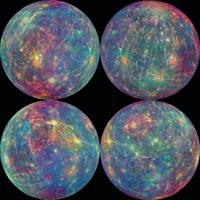

LIKE EARTH, Mars, and Venus, Mercury is a rocky planet. Though it has only 5% the mass of Earth, it's denser than every other planet including Earth, if you take into consideration the smaller gravity of Mercury. Mercury's surface is made of the same groups of silicate minerals found on Earth, Earth's moon, and Mars, such as olivine, feldspar, and pyroxene. But although Mercury's silicate minerals have the same crystalline frameworks as Earth's, Mars's, and Venus' minerals, their chemical compositions are different, Sprague says.

For example, very little iron appears to be in the lattice structure of Mercury's olivine and pyroxene, whereas iron constitutes up to 20% of the same minerals on Earth. Perhaps Mercury's iron is sequestered in its core or is removed from the surface by weathering processes.

Mercury's very thin atmosphere consists of a dilute collection of potassium, calcium, hydrogen, helium, and sodium atoms that escape into space but are continuously replenished as the surface evaporates or as the surface is hit by solar wind particles or meteorites.

Messenger will also look for ice, perhaps deposited by comets, which might occur as dust-covered ice patches protected within craters that never see the sun.

The interest in Mercury isn't a flash in the pan. The European Space Agency and Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency are following up with a joint mission to Mercury scheduled for launch in 2013. Named BepiColombo after the Italian astronomer Giuseppe (Bepi) Colombo, the mission's two spacecraft—planetary and magnetospheric mappers—will begin orbiting Mercury in 2019.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter