Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Policy

Who's Next?

Veterans of past layoffs tell those facing the ax in the pharma industry what they can expect

by Linda R. Raber

March 16, 2009

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 87, Issue 11

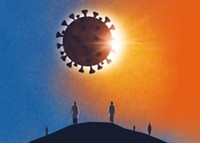

"LOOK TO YOUR LEFT. Look to your right. One of you won't be here next year." This old saw is neither funny nor fair when intoned by tough-talking professors on the first day of freshman chemistry. Unfortunately, the much-repeated phrase is becoming true in today's pharmaceutical industry.

Mass layoffs are ill winds ripping through the global workforce. Large pharmaceutical companies with meager pipelines, evaporating patent protection, and fierce competition from generic drug manufacturers are scrambling to make money. Executives are responding to shareholder demand for increased earnings by using contract research organizations, sending work overseas where labor is cheaper, instituting reorganizations aimed at doing more with less, and shedding less profitable business units. All of these actions shed jobs, too.

Take Your Job Search To The Net

BioJobBlog

This blog is published by a self-described "former medical school professor, industrial scientist, professional recruiter, management consultant, entrepreneur, and career development expert who has been around the block and wants to share his experiences to help others launch successful careers in the bioscience industry."

Cafepharma

Aimed at pharmaceutical sales professionals, this site gives the lowdown on specific companies. Be warned that the site includes angry rants and off-color humor. Check out the specific company message boards for information from salespeople, whom many regard as pharma's bellwethers.

In The Pipeline

Derek Lowe, a Ph.D. organic chemist, has worked for several major pharmaceutical companies since 1989 on drug discovery projects against schizophrenia, Alzheimer's, diabetes, osteoporosis, and other diseases. His blog is well researched, thoughtful, and well written. It's the top source of news for many of those interviewed for this article.

FiercePharma

This blog bills itself as "the pharma industry's daily monitor, with a special focus on pharmaceutical company news and the market development of FDA-approved products." The site and its sister site, "FierceBiotech" (fiercebiotech.com), contain up-to-the-minute news and information.

In Vivo Blog

This site features daily commentary on recent developments in biopharmaceutical business development, R&D, financing, marketing, and policy. It is published by FDC-Windhover/Elsevier Business Intelligence.

WSJ Health Blog

This Wall Street Journal blog aims to offer "news and analysis on health and the business of health." The lead writers are reporters Jacob Goldstein and Sarah Rubenstein. The blog also includes contributions from other staffers at the Wall Street Journal, wsj.com, and Dow Jones Newswires.

BNET Pharma

Jim Edwards, a former managing editor of Adweek who covered drug marketing at Brandweek for four years, writes this blog, where he offers news and insights about the industry. He is a former Knight-Bagehot Fellow at Columbia University's business and journalism schools. He also writes Jim Edwards' NRx (jimedwardsnrx.wordpress.com), which he claims contains "drug business stories the media hasn't written yet."

Pharma Marketing Blog

This blog aims to help pharmaceutical marketers advance their careers through networking, sharing resources, and continuing professional education. It is full of detailed information and is entertaining to boot.

Almost 130,000 pharmaceutical industry workers, primarily in the U.S. but also in Europe, have been laid off in the past three years, C&EN calculates from news reports and other sources. Laid-off pharma workers have been swept into unemployment and financial distress. Losing jobs in a historical moment described every day as having the worst economic conditions since the Great Depression only makes the situation for these unemployed masses more grave.

For example, in 2007, Pfizer, Bayer, Johnson & Johnson, GlaxoSmithKline, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and AstraZeneca announced that about 38,000 employees would be laid off among them. Last year, Merck & Co., BMS, GSK, Schering-Plough, and Wyeth cut a total of about 25,000 jobs. So far this year, the proposed purchase of Wyeth by Pfizer alone is likely to put about 26,000 workers in the crosshairs. Since then, GSK and AstraZeneca have announced 12,000 more job cuts altogether, and last week, Merck announced its $41.1 billion takeover of Schering-Plough and the likely layoff of 16,000 workers over the next several years.

The job cuts in pharma are across the board. Pharmaceutical sales forces are being hit hard. R&D positions, many of them held by chemists, are also being slashed.

Although unemployment can be devastating in the short term, most people who have been cut in past layoffs have found jobs quickly. But now job searches are taking longer, according to a recent survey of 3,000 job seekers conducted by Challenger, Gray & Christmas, a firm that helps executives and middle managers find jobs after they've been let go. The median time for successful job seekers to find a new position grew from 3.6 months in the second quarter of 2008 to 4.4 months in the third quarter. The survey also found that 13.4% of job seekers relocated to take new positions in the third quarter of 2008.

The situation is tougher for many of the technical professionals in pharma who have lost their jobs. Josh Albert, managing partner of Klein Hersh International, an executive search firm in Willow Grove, Pa., says the "top 15–20%" of scientists in pharmaceutical firms who are being laid off will have multiple offers of employment from multiple companies. "The middle 50% will find a job, but it's going to take them a year. Everyone else is going to need to look into different career paths." When Albert discusses who falls into these categories, he regards career success in terms of promotions, publications, and getting drugs into the clinic.

FOR THIS ARTICLE, C&EN interviewed 12 scientists who work as chemists or other types of molecular scientists and were laid off from pharmaceutical research positions over the past several years. On the condition of anonymity, they shared details about the layoff process and how being let go has affected them emotionally, financially, and professionally. Their names and other potentially identifying information have been changed. The layoffs they describe took place between 2003 and late January 2009.

"James," a Ph.D. chemist in his late 40s, has been working in drug discovery for 20 years and is a veteran of two layoffs, the most recent in 2003. He says he is "reading the writing on the wall" and is not optimistic about his chances of making it through 2009 with a job. James is currently looking for new employment, but he's also trying to keep his fingers on the pulse of his company, which is involved in a major reorganization.

Company spokespeople are not forthcoming with information about when and how the ax will fall, James says, so he's getting much of his information from the Web. A lot comes from another medicinal chemist, Derek Lowe, who publishes the blog "In the Pipeline." James and others also follow the sometimes vulgar but often prescient message boards on Cafepharma. On this site, pharma sales reps vent their frustrations and divulge confidential company information about layoffs and other business decisions. The information is on-target often enough that it ought to cause pharma executives sleepless nights. "If there is a lot of activity on a particular company's board on Cafepharma, you can bet that something is afoot in the executive suite," James says

For example, a post on the Merck board dated March 7, two days before the Merck takeover of Schering-Plough was announced, reads, "Definitely something is up at HQ. Lots of scurrying around and buzz. Sorry to hear it may be" Schering-Plough. On the Schering-Plough board, "Merck person here. Definitely something up on our side so it must be true that we are bidding. Very disappointed that we can't do better than buying you."

Although increased blog chatter about boardroom negotiations may signal an approaching reorganization, individuals learn their own fates in myriad ways. There are also, however, signature signs that a pink slip is coming. Several scientists shared their first inklings that something was going to happen, and the signs weren't subtle. Of his 2003 layoff, which followed a merger, James says that he knew he was a short-timer when he started reporting to "a kid with only two years' experience." James says his first duty was to teach his new boss medicinal chemistry. That done, James was laid off.

Also in 2003, "Mark," a Ph.D. who is now 64, was laid off from a small pharma firm. He says—and C&EN verified through court filings and the business press—that his company's chief executive withheld negative information from its employees and shareholders about the likely results of a clinical trial. The CEO knew that the company's "product was demonstrably inferior to a competitor's, and we had no data to prove otherwise. The stock plummeted, and we all knew a shake-up was pending," he says. Being well along in his career, Mark says he was happy to be let go, took his severance pay, and left.

On the first day of her maternity leave in 2005, "Barbara," 38, a Ph.D. medicinal chemist, was notified that her work site would close. She was taken by surprise and says that even the rumor mill failed. "This was a huge, stressful event for all of my colleagues. It caused a great deal of hardships for families," she says. "For me personally, it took what should have been a very joyous time and made it incredibly stressful." She had the option to keep her job, but it would have meant moving halfway across the country where there wouldn't have been a job for her husband. She is now working at a small specialty chemical company near her home.

"Be flexible in your expectations and sell your skills and abilities."

Another sign that you might be getting laid off is finding, suddenly, that you can't log in to your computer. "Rick," 46, a Ph.D. chemist, was laid off from a small firm in Toronto late last year. He got to work one morning and noticed "someone had been mucking around" with his computer. There were strange icons on his desktop, and he couldn't log in to the network.

"The computer guy wouldn't answer the phone," he says, "so I went to see him, and he wouldn't meet my eye." Within a few minutes, Rick was in a room with his boss and a human resources person, who, sounding like she was working from a script, told him he was being let go. He was allowed to return to his office to pack his belongings but then was required to leave the premises immediately.

Everyone interviewed for this article recounted some version of this scenario—the meeting, the scripted talk, and an invitation to pack and go. Those laid off received between five minutes and several months' notice. Some were discharged by conference call or received the bad news just months after being assured that their jobs were safe. At least severance packages generally have been good, and companies have offered outplacement services. Still, the common denominator is intense emotion.

"Adam," a chemist in his mid-30s with a bachelor's degree, was one of the 800 researchers laid off by Pfizer at the end of January. He got a couple of weeks' notice and a "decent" severance package, he says. Talking to C&EN just days after being laid off, Adam's emotions were raw. He says he is angry that Pfizer's management "didn't keep their promise to keep workers in the loop." He received "more tangible information from blogs online and the local newspaper," he says.

"I AM FILLED with anxiety and confusion. I've lost direction, desire, and focus on pretty much everything. I will have no income and about one month's worth of savings. Insurance is going to kill us if I don't get something in a few months," Adam says.

James says that many pharma employees feel outright betrayal. "I know many chemists who loathe upper management because they are so out of touch with what's going on," he says. He deplores executives who have devalued U.S. science by firing highly skilled and knowledgeable researchers, abandoning drug pipelines, and outsourcing so much work to India and China. "We've gutted ourselves," he says.

Despite the current downturn, Klein Hersh's Albert is as "enthusiastic as ever" that small-molecule drug discovery will be done within the U.S. "It will be different, but it will evolve and it'll be a good place to earn a living and a great place to make drugs that will help humans," he says.

Albert's clients are pharmaceutical companies. They pay his search firm a percentage of the first year base salary, usually 25–30%, for any of his referrals they hire. There is no cost to the job seeker. He says that despite the layoffs, big pharma companies are using his services just as much as ever to supply them with interested, motivated candidates committed to making a career move, and his "phone is ringing off the hook" with inquiries from scientists looking for jobs.

In addition to working with a recruiter, who will have lots of highly qualified candidates for a very few positions, job seekers can turn to a number of resources. Many scientists are using online job-posting websites like monster.com, indeed.com, biospace.com, www.acs.org/careers, and biocom.org.

James is using all of these outlets, plus usajobs.gov, the consolidated recruiting site for all employment with the U.S. government. "The Centers for Disease Control & Prevention and the Department of Homeland Security, for example, need people with advanced degrees in earth sciences who can bridge the gap between researchers and nonresearchers," he says. The jobs aren't listed under "chemist," however. James advises jobseekers to use "scientist" as a search term and to "get started soon. Government jobs can easily take six to nine months to line up," he notes.

Although age discrimination is neither ethical nor legal, it is, according to those interviewed, a fact of life. James believes that younger Ph.D.s who love chemistry would be well advised to aim for careers in academia and strongly consider bypassing the pharmaceutical industry, at least for now. He says limitations on publishing, confidentiality rules in the pharma sector, and his age have made him unsuitable for any faculty positions like those for which he was recruited after completing his postdoc 20 years ago. Rick agrees. Let go from a position doing protein modeling and computational chemistry at age 46, he was told flat out by a university faculty member that he was simply "too old for a postdoc" and to forget it.

Advertisement

NETWORKING opportunities—either in person or online through social networking sites—are proving useful for some job seekers. "Ann," 40, who has a master's degree in chemistry and an M.B.A., was laid off a little more than a year ago from a research position at a small West Coast pharma firm. She tells C&EN that the outplacement services provided by her employer after the layoff were very helpful.

Ann's employer hired a firm to help layoffs polish their résumés and interviewing skills. She says that she and about 10 other job seekers in different fields decided to meet on Monday mornings and compare their progress. "We chart how many letters we've sent, how many hiring manager contacts we've made, and how many résumés we've sent out," she says. She credits this group with helping her to overcome her natural introversion.

Ann and other scientists C&EN interviewed are also using the social networking site LinkedIn. She uses this more professional cousin of Facebook by "looking at the profiles of other people whose career paths interest me by searching for people in drug development. I contact them and ask them for career transition advice," she says. She has found that many of these contacts are helpful and some of the scientists there are very generous with good advice.

A veteran of several layoffs, "Martin," 40, advises those anticipating being let go to work their networks and "think outside the traditional industry 'box' of potential jobs. If you constrain yourself to only one type of industry or job, you are limiting yourself. Be flexible in your expectations and sell your skills and abilities."

Two of those interviewed—Ann and Mark—tried stints at teaching. Ann taught chemistry at a local community college before getting a permanent job at a software company several weeks ago. Mark did some substitute teaching and then easily passed his state teaching certification tests in chemistry and biology. Although he loved substitute teaching, he "really couldn't stand today's teenagers." He doesn't follow up on ads for teachers anymore; he has decided to remain retired.

Referring to his employment history, "Bob," 40, who has worked for four different pharma firms in the past 15 years, says, "You can see that layoffs and site closures are becoming the norm. I think that everyone who is working today can expect to be involved in at least one layoff or site closure, if not several, during the course of their career."

It's "sad to say, but the days of working for only one firm during your career are long gone, and the days of forced severance are here," Bob adds. "In this environment, the best you can do is to be active in your chemistry community and maintain your network as if you are in imminent peril of being the next on the chopping block."

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter