Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Biological Chemistry

Newscripts

Taking On The Locoweed, Bee Medicine

by Ivan Amato

July 20, 2009

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 87, Issue 29

When settlers pushed forward on America's western frontier in the 1800s, they noticed that their horses, cattle, and other livestock sometimes began to stagger and skitter and stare vacantly. Some of the afflicted animals eventually would become emaciated and scraggly and die. The syndrome, known as locoism, remains a big problem today.

The culprits, says plant physiologist Daniel Cook of the Department of Agriculture's Poisonous Plant Research Laboratory, in Logan, Utah, are LOCOWEEDS, primarily Astragalus and Oxytropis species that grow in large swaths of Wyoming, Texas, Colorado, and other western states where livestock graze. Locoweed poisoning hits the livestock industry each year with a $100 million loss, Cook says.

The agent behind locoism is the toxic alkaloid swainsonine, apparently produced by an endophytic fungus living inside the plants' cells. A mimic of the sugar mannose, swainsonine interferes with mannosidase enzymes. As a consequence, oligosaccharides end up accumulating inside cells, eliciting what Cook describes as "cellular constipation." Swainsonine also messes with glycoprotein synthesis, so it throws signaling, adhesion, movement, and other cellular functions out of whack. It all sums up to animals that are in a very bad way.

For their part in the effort to safely open more rangeland to grazing, Cook and his colleagues have developed a polymerase-chain-reaction technique for identifying even vanishing amounts of swainsonine-producing fungus in locoweeds. "We want to better characterize the relationship between plant, endophyte, and toxin," says Cook, noting that the ultimate goal is "to come up with some method to render locoweeds nontoxic." The researchers report their method and initial results in the Journal of Agricultural & Food Chemistry (2009, 57, 6050).

Even as swainsonine makes livestock sick and crazy in their home on the range, another natural product, PROPOLIS, which is an antiseptic hive sealant made by bees, keeps on revealing more medicinal potential.

Propolis is a resinous substance that bees collect from the buds and bark of trees such as poplar and pine and then enzymatically transform into what appears to be an antiseptic sealant, says beekeeper Royal W. Draper, owner of Draper's Super Bee Apiaries, in Millerton, Pa. Draper, whose primary business is selling honey, is part of the small but worldwide supply chain that harvests propolis and sells it into the alternative medicine market where powders, tinctures, and other preparations of the stuff are sold and used to treat everything from eczema to fungal infections to inflammation-based diseases.

It's also shown an ability to kill some cancer cells, but propolis composition varies depending on the region and bee species involved. And that means any medicinal properties of propolis are likely to change from batch to batch. Shigetoshi Kadota of the University of Toyama, in Japan, and his colleagues there and at the National Cancer Center Hospital East, in Chiba, Japan, have been collecting propolis from different global locations.

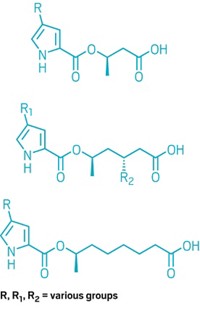

One of their latest samples, from Ywar Taw village, in Myanmar, yielded a tantalizing anticancer lead. The scientists isolated 17 compounds and tested their lethality on a line of human pancreatic cancer cells that in previous studies had succumbed to extracts of Brazilian red propolis. In test-tube studies, one of the compounds proved remarkably lethal to the cells, the researchers report in the Journal of Natural Products (DOI: 10.1021/np9002433).

Although the data are merely suggestive of the compound's potential clinical value, it is the sort of scientific finding that Draper says he loves to hear. He notes that it only helps his propolis business, which he estimates brings in a few thousand dollars per year.

Ivan Amato wrote this week's column. Please send comments and suggestions to newscripts@acs.org.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter