Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Business

Chemtura Charts A Comeback

CEO Craig Rogerson hopes firm will emerge from bankruptcy in March 2010

by Marc S. Reisch

September 14, 2009

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 87, Issue 37

March 2010 is the target date for Chemtura’s emergence from bankruptcy, Chief Executive Officer Craig Rogerson tells C&EN. If Chemtura succeeds in achieving that goal, the $3.5 billion-per-year specialty chemical maker will have entered and left bankruptcy reorganization in just one year.

Other chemical firms have had tough and lengthy tenures under bankruptcy court supervision. Dow Corning spent nine years in bankruptcy, Solutia spent four years, and W.R. Grace has been under court supervision for eight years and counting. Only polyester maker Wellman managed to wrap up its bankruptcy case in one year when it emerged as a private company in January.

Automakers General Motors and Chrysler recently sailed through their bankruptcy reorganizations in a matter of months, backed as they were by government bailouts. Chemtura has no such sugar daddy in Uncle Sam, but Rogerson hopes that Chemtura’s time under reorganization, now approaching the six-month mark, will come closer to Wellman’s experience than to Dow Corning’s.

Key milestones achieved so far, Rogerson notes, include preparation of a five-year business plan that is now being reviewed by court-appointed creditor committees. And the judge overseeing Chemtura’s bankruptcy case in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York has set the bar date—the deadline by which anyone who has claims against the company must file with the court—for Oct. 30. When the deadline passes, Chemtura can tally up all the claims against it and submit its plan for reorganization by late December.

Still, by the time March 2010 rolls around, Chemtura will have to win creditor approvals for its business and reorganization plans, get creditors to agree on who will own what portion of the new Chemtura, secure financing, and get the bankruptcy judge’s blessing. None of these steps is easy. “We don’t control all the variables,” Rogerson acknowledges, and any number of factors—such as creditor objections or how the judge will rule on various issues—could delay Chemtura’s emergence from bankruptcy.

But a relatively quick trip through bankruptcy may be in the cards for Chemtura, says John Roberts, a chemical analyst with investment advisory firm Buckingham Research. Other firms had very complicated liability situations that kept them in reorganization for a long time, Roberts points out. Dow Corning had multi-billion-dollar breast implant liabilities, Solutia had significant pension and environmental problems, and Grace has significant asbestos claims against it. Both Chemtura and Wellman have had to deal with a relatively uncomplicated “overleveraged debt situation,” Roberts notes.

When Chemtura filed for bankruptcy on March 18, the firm faced a July deadline to repay a $374 million note. At the time, the credit markets were virtually frozen, and it had no prospects to refinance the note. “We didn’t file because we had a profitability issue; we filed because we had a short-term liquidity issue,” explains Rogerson, who had joined Chemtura just three months earlier. It was a decision Chemtura made because it had run out of other options.

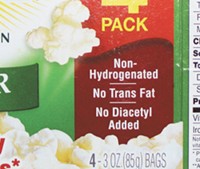

Under bankruptcy, other matters are also likely to be beyond Rogerson’s control. One example is a series of product liability claims filed against Chemtura as a supplier of diacetyl, a butter flavoring ingredient known to cause lung disease among workers at microwave popcorn factories. Popcorn makers stopped using diacetyl in 2006. But since then, suits filed on behalf of about 50 workers against flavoring manufacturers such as International Flavors & Fragrances and Givaudan have also named Chemtura.

According to documents Chemtura’s lawyers filed in court hoping to stave off the suits during bankruptcy, “the diacetyl-related claims are potentially among the largest unsecured claims pending against the [Chemtura] estate.” The documents note that settlements reached by other parties to date have been about $2 million per claimant before trial and as much as $20 million per claimant after trial.

Although Rogerson admits that Chemtura’s potential liability is large, he maintains “it would be nothing like a billion dollars,” a figure arrived at by multiplying the number of claims involving Chemtura and the highest payout made to date. “We haven’t paid anything on those claims,” Rogerson says, “and we still protest those claims.”

Other actions that could delay Chemtura’s emergence from bankruptcy are ongoing squabbles between secured and unsecured creditors and negotiations surrounding environmental liabilities. However, the bankruptcy process has helped Chemtura reduce its liability in at least one instance. The company succeeded in negotiating a reduction in outstanding antitrust fines owed to the U.S. and Canadian governments from $18.5 million to $11.6 million and increasing the length of time it has to pay the fines. The fines go back to a 2004 plea of guilty to fixing prices on rubber chemicals.

Before Chemtura filed for reorganization in March, it had planned to sell one of its more profitable businesses, such as crop protection or pool chemicals. Rumors persist that the firm is selling one or another of its businesses, but Rogerson insists he has no immediate plans to sell any business.

“It is appropriate now to recognize there is little common link between Chemtura’s businesses,” Rogerson observes. “That is in large part because Chemtura was formed through mergers of firms including Uniroyal Chemicals, Bio-Lab, Great Lakes, and Witco. We got some corporate synergies from those combinations, but really what we have now is a portfolio of businesses,” he points out. “One of the corporation’s roles has to be managing this portfolio. So at the right time, any of our businesses could be for sale.”

Rogerson goes on to say, “Our five-year long-range plan presumes we are running all our businesses. It does not presume we are selling our businesses.” Those plans also call for hiring new researchers and increasing R&D budgets in areas such as organometallics, petroleum additives, crop protection, and flame retardants, especially to make up for a gap in the new-product pipeline that is likely to emerge after 2011 because of earlier R&D cutbacks.

The long-range plan doesn’t envision divestitures, and it doesn’t provide for mergers or acquisitions. It does envision sourcing more raw materials from Asia and forming ventures and alliances in the East, “where our currency may be technology or market access with someone who wants to put assets in the ground,” he says.

Rogerson admits that “there has been no lack of hurdles and issues and obstacles” in the way of getting through bankruptcy in a year’s time. “But so far,” he says, “we have been getting over them, and that has got to continue. We can see the light at the end of the tunnel, and it’s not a train coming.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter