Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Business

The Problem With Butter Flavor

Accused by some of causing lung disease, diacetyl is the subject of widespread lawsuits

by Marc S. Reisch

November 16, 2009

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 87, Issue 46

A butter-flavor ingredient widely considered safe has spawned a wave of lawsuits that could cost chemical companies and flavor manufacturers hundreds of millions of dollars.

Although the first suits were filed in 2001, the legal storm is only now gaining force. Attorneys say the ingredient, diacetyl, won’t be the next asbestos or silicone breast implant, but they do warn that chemical companies will be hearing about diacetyl for some time to come.

By one account, some 300 lawsuits are wending their way through U.S. courts. They charge that diacetyl, which the Food & Drug Administration classifies as “generally recognized as safe,” causes lung disease in factory workers. Most of the cases involve workers who were exposed to high concentrations of the ingredient during the manufacture of microwave popcorn. But some workers who make other butter-flavored foods, such as hard candy, claim they are ill, too.

Many workers have been diagnosed with bronchiolitis obliterans, a rare lung disease that causes shortness of breath, coughing, fatigue, and ultimately death. Because of the large number of popcorn workers who say exposure to diacetyl made them ill, bronchiolitis obliterans is often referred to as popcorn lung disease.

Most food manufacturers no longer add diacetyl to their microwavable popcorn. This has been the case since 2007, for example, for ConAgra Foods, maker of Orville Redenbacher-brand popcorn. In a few instances, consumers have charged that vapors from microwave popcorn eaten in the past have also made them sick.

The list of defendants in the popcorn cases reads like a who’s who of the flavoring world with firms such as Givaudan, International Flavors & Fragrances (IFF), Sensient Technologies, and Cargill Flavors. In addition, the suits name manufacturers and distributors of flavor ingredients such as BASF, Chemtura, Citrus & Allied Essences, and Polarome International.

Popcorn makers and other food processors have occasionally also been targets of worker lawsuits. But worker compensation laws in many states limit the legal remedies open to employees who claim they’ve been injured on the job, so popcorn lung suits are mostly aimed at flavor makers.

As a group, the popcorn lung cases are a cautionary tale, says trial lawyer Kenneth B. McClain, who represents workers from all over the U.S. “They highlight the risk of food additives that no one has tested but that everyone assumes are safe because they are on FDA’s generally recognized as safe list,” he says.

The first suits, targeting IFF and other flavor makers, involved 47 people who worked for Gilster-Mary Lee Corp.’s microwave popcorn plant in Jasper, Mo. McClain had a hand in all these actions and in most others since 2001. In eight cases that went to trial in Jasper County Circuit Court, four verdicts exonerated IFF. However, four went against IFF in 2004–05, with verdicts that ranged from $2.7 million to $20 million. All were subsequently settled for undisclosed amounts.

Another case, tried in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Iowa, initially named Givaudan, as well as Sensient, Flavors of North America International, and IFF, for damaging the health of American Popcorn worker Ronald Kuiper. In March, Kuiper won a $7.5 million verdict against Givaudan alone. That case, too, was subsequently settled out of court for an undisclosed amount.

McClain says he represents about 500 individuals in 300 popcorn lung cases pending in U.S. courts. Exact figures are difficult to come by because of the large number of autonomous state and federal courts. In addition to representing plaintiffs in court, McClain and his firm, Independence, Mo.-based Humphrey Farrington & McClain, have negotiated hundreds of confidential settlements on behalf of workers. To attract clients, the firm snapped up the URL www.popcornlung.com.

Even though McClain estimates that companies and their insurers will pay out hundreds of millions of dollars to popcorn lung sufferers, “these suits are not going to bankrupt anyone,” he says. And they aren’t of the same stature as the asbestos cases that bankrupted Johns Manville or the silicone gel breast implant suits that forced Dow Corning into bankruptcy. “But they are larger than you think,” McClain warns.

Defense attorney Jason F. Meyer, who represents two diacetyl distributors—Penta Manufacturing and Citrus & Allied Essences—in California cases now in litigation, says science hasn’t yet caught up with the facts. He contends that the science will be unlikely to show a clear connection between diacetyl and lung disease.

Plaintiffs’ attorneys had some early successes, admits Meyer, who is a partner in the San Diego office of law firm Gordon & Rees. But he predicts that, as the science improves, plaintiffs’ attorneys will have a difficult time finding credible expert witnesses who can make a connection that will stand up in court.

However, verdicts such as the recent one against Givaudan have enlivened interest in the diacetyl suits among law firms, chemical companies, and the insurance companies that often have to settle on behalf of corporate customers. Legal issues teleconference provider HB Litigation Conferences arranged two conferences on popcorn lung suits this year, conference developer Jaimee Taibi says. The firm had such a good turnout for the July conference that it held an update last week.

Despite the millions of dollars involved, Wall Street analysts seem untroubled. “These cases have been going on for many years,” says John Roberts, an analyst with the investment advisory firm Buckingham Research. “So it’s viewed as a normal ongoing cost of operating in the U.S. system.”

Diacetyl exposure has been a concern in microwave popcorn facilities since at least 2000, when Missouri’s health department investigated a cluster of bronchiolitis obliterans cases at the Gilster-Mary Lee plant. The National Institute for Occupational Safety & Health also investigated and found other clusters of disease that appeared to be associated with diacetyl. In December 2003, the agency proposed stricter limits on worker exposure.

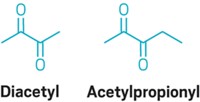

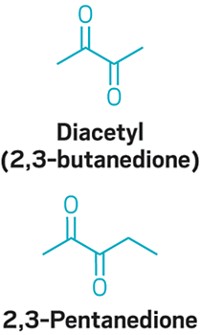

Despite the hullabaloo concerning popcorn lung, FDA still considers diacetyl a safe substance because it occurs naturally in foods such as butter and milk. In levels common naturally in food, diacetyl is safe, notes flavor chemist Devin G. Petersen. “The health-related issues,” he says, “seem to be related to higher exposures than are typical in life.”

Petersen, who is an associate professor at the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities, points out that diacetyl has a low boiling point and is volatile. “In industrial settings, exposure to diacetyl molecules could be higher than in most other settings,” he says.

The possibility that exposure to high concentrations of diacetyl might cause lung disease convinced the Flavor & Extract Manufacturers Association (FEMA) to recommend more stringent handling requirements for it. John B. Hallagan, FEMA’s general counsel, acknowledges that FEMA has been targeted in a number of diacetyl cases, but he says the trade group has been dismissed from all of them.

Hallagan says he can’t comment further on the litigation and thus could not say why the association was named in some diacetyl suits. Lawyers whom C&EN spoke with say the group was included because it works with FDA regulators to help determine which flavors can be designated “generally recognized as safe.”

Tracking exactly how many cases are pending nationally and even from company to company can be something of a spectator sport. Flavor and chemical companies contacted by C&EN all declined to comment on the cases.

As of mid-June, Chemtura, which is now undergoing bankruptcy reorganization, had 14 diacetyl cases pending against it involving 46 claimants. In documents filed in federal bankruptcy court as part of Chemtura’s reorganization, the firm’s attorneys say “the diacetyl-related claims are potentially among the largest unsecured claims pending against the estate.”

In recent filings with the Securities & Exchange Commission, IFF says it now has 19 actions involving 340 claimants pending against it. During 2008 alone, plaintiffs’ attorneys filed nine new actions against IFF involving 73 claimants. Last year, the firm says, it settled or was dismissed in seven actions involving 23 claimants “for a net out-of-pocket amount which is not material to us, including insurance recovery.” In addition, IFF says, the courts dismissed 338 butter flavor claims because they “lacked merit.”

IFF says it doesn’t expect the pending cases to have “a material adverse effect on our financial condition.” In a discussion of the popcorn lung cases also contained in the government filings, IFF says its defense posture along with its insurance coverage will keep expenses down.

Givaudan does not give a periodic accounting of how many cases are pending against it, but the company has hinted at how costly such suits are. In January 2007, it revealed an August 2006 settlement with 51 diacetyl injury claimants. And although it did not reveal the cost of the settlement, the company recorded a charge of about $35 million against earnings to cover part of the settlement that its insurers did not pick up.

Even if these worker suits are just an irritant and a cost of doing business, flavor makers may have more to worry about if consumer suits gain traction. Plaintiffs’ attorney McClain has filed three separate suits against butter flavoring companies, microwave popcorn manufacturers, and grocery store food distributors on behalf of snack lovers who consumed multiple bags of popcorn daily and now claim to have lung disease.

The first case, filed in 2008, involves Wayne Watson. The popcorn aficionado went on television in September 2007 to say that he loved microwave popcorn so much he ate at least two bags each night, breathing in the steam from the just-opened envelope. Watson only stopped the practice when doctors told him it may have made him sick.

Watson’s case garnered much attention. “We get calls from consumers every day,” McClain says.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter