Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Biological Chemistry

Neuroscience: The Two Faces Of Pleasure And Desire

by Sophie L. Rovner

March 15, 2010

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 88, Issue 11

Think of that lovely flush of pleasure you get when you bite into a Godiva chocolate. Now that you've had that first bite, admit it, you crave another.

These two sensations—liking and wanting—unite to create what's known as "food reward." Scientists are gradually piecing together the neurochemical, biological, and psychological factors that underlie this experience. They're also exploring how these factors contribute to disorders and addictions.

For most people, the sensation of wanting goes hand in hand with liking or, as University of Michigan neuroscientist and biopsychologist Kent C. Berridge terms it, the hedonic pleasure of reward. But he notes that "there may be a number of clinical conditions, like drug addiction and certain eating disorders, that pull them apart so that wanting, for example, soars above the amount of pleasure that the food is giving."

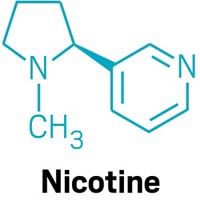

Drugs can even change the brain "to magnify the wanting circuit in a nearly permanent way," he says. "So addicts can want their drugs, even though they are not in withdrawal and even though the drugs don't give them much pleasure."

This divergence can develop because the sectors of the brain that are activated by food contribute to different psychological components of food reward, Berridge says (Physiol. Behav. 2009, 97, 537). For instance, he believes that dopamine signaling in the brain controls the desire for pleasure. Experimentally stimulating dopamine release increases the motivation to obtain pleasures such as food rewards, "but it doesn't seem to increase the hedonic impact of those pleasures," he explains.

On the other hand, experimentally stimulating neurons in a part of the brain's nucleus accumbens with compounds that mimic endogenous opioid neurotransmitters elicits both a desire for and enjoyment of food.

Yet this "hedonic hot spot" occupies only about 10% of the nucleus accumbens, Berridge and his colleagues found. If opioid receptors on neurons in the rest of the nucleus accumbens are stimulated, "the wanting comes on, but not the hedonic impact," he says. "So this tells us that the brain is much more stingy" with structures—also known as substrates—that underlie the feeling of pleasure "than with its substrates for the desire for pleasure," he says.

Other brain sectors also contribute to food reward. For instance, neurons in the nucleus accumbens connect with the ventral pallidum, which Berridge's team showed has its own hedonic hot spot that can mediate both liking and wanting.

Wanting is often triggered by cues such as aromas or the sight of someone else indulging in an activity. Seeing another smoker light up can prompt people who are trying to quit to get out their own cigarettes. Even if the visual cue doesn't entice them, "the smell of the cigarette may be harder to resist," Berridge acknowledges. Likewise, recovering alcoholics have told him they can be around people who are drinking and can resist imbibing unless they catch a whiff of alcohol. So odors are very powerful for turning on the desire for drugs and food, Berridge says.

If the drive is strong enough, people will overindulge, for instance by eating past the point of satiation. "Satieties can suppress the reward circuit, but they don't suppress it to zero," Berridge says. "So it's hard to completely turn off the ability of pleasant foods to elicit a wanting for more. And because we're surrounded by pleasant foods and cues for them, we keep on nibbling.

"That's something that we all share," he confesses. But research suggests that some binge eaters who are obese possess genetic alleles for opioid and dopamine receptors that "produce a heightened liking and wanting for foods that most of us don't have to experience and don't have to resist," he says.

What can a consumer do to fight back against overindulgence? "Satiety grows in a little bit slow" when eating, Berridge notes. "If you space the bites out, it can help. If you have a portion, and then you wait a little bit before deciding to have the next portion or not, that can help. But when you get a big mound on the plate, you tend to eat right through it."

Consuming food that's interesting and flavorful can help, too. Berridge suggests "focusing on the quality and not the quantity" of the food. "Each bite is interesting, so it can be cherished."

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter