Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Safety

Napolitano Pushes Chemical Security

Administration wants congress to extend antiterrorism standards for chemical plants

by Glenn Hess

July 26, 2010

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 88, Issue 30

The Obama Administration is working with Congress to strengthen a temporary federal program designed to protect U.S. chemical facilities against potential terrorist attacks, the nation’s top security official told an industry conference earlier this month. But the chemical industry, although agreeing that the current program needs to be extended, wants no part of a key element of the Administration’s proposal.

“I am confident we will find common ground with Congress to permanently authorize the Chemical Facility Anti-Terrorism Standards” (CFATS), said Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Secretary Janet Napolitano. She gave the keynote address at the 2010 Chemical Sector Security Summit, a two-day event that kicked off on July 7 and drew more than 400 participants to Baltimore. It was funded by DHS and the Society of Chemical Manufacturers & Affiliates (SOCMA), a trade association.

Chemical industry officials and congressional aides attending the summit indicated that Congress is more likely to approve a one-year extension of the current CFATS program as the legislative calendar winds down. DHS’s authority to continue implementing and enforcing the three-year-old chemical security regime expires on Oct. 4.

“Not all facilities need the same level of security,” Napolitano noted. “We need to identify and secure those facilities that, if attacked, would endanger the greatest number of people.” If CFATS is allowed to expire, the secretary cautioned, it could “disrupt” efforts under way by government and industry to safeguard 5,000 “high risk” chemical facilities against a variety of threats, including terrorism.

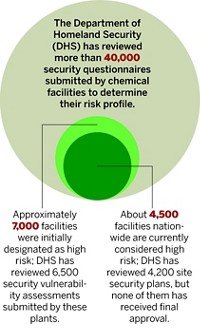

Under CFATS, facilities are required to assess their vulnerabilities, such as whether their perimeters, access points, and computer systems are secure. Facilities designated as high risk—because they produce, handle, or store threshold quantities of certain hazardous chemicals—are required to develop site security plans and implement protective measures. DHS then conducts audits and inspections to ensure compliance.

“Securing our nation’s chemical sector requires extensive collaboration with our private-sector partners,” Napolitano said. “Flexible, practical, and collaborative programs such as DHS’s National Infrastructure Protection Plan and CFATS play a key role in enhancing the security and resiliency of our nation’s chemical facilities and other critical infrastructure.”

Napolitano also cited the need for a coordinated effort among multiple agencies and missions within DHS. The Coast Guard, for example, has significant regulatory authority over chemical facilities along ports and waterways, and the Transportation Security Administration works with industry to protect hazardous chemicals transported by rail and pipelines, she said.

In her remarks, Napolitano also reaffirmed the Administration’s support for adding provisions to CFATS that would require the highest risk chemical facilities to adopt so-called inherently safer technology (IST), which can include the replacement of hazardous chemicals with less-toxic alternatives.

Napolitano acknowledged that there are “some differences of opinion” over whether an IST mandate should be included in security legislation. But she added, “Let me just say this: We support the use of safer technology such as less-toxic chemicals where possible to enhance security. But we also recognize that as we seek to manage risk, we need to balance the costs and benefits associated with doing so.”

The House of Representatives approved the Chemical & Water Security Act (H.R. 2868) in November 2009. The bill would give DHS permanent authority to establish and enforce security standards at chemical facilities. Wastewater treatment plants and drinking water facilities would also be required to adopt security measures.

Most notably, the legislation would grant DHS new power to order the riskiest facilities to replace dangerous chemicals and processes with alternatives that are safer and more secure where technically feasible and cost-effective. Sen. Frank R. Lautenberg (D-N.J.) introduced a similar measure (the Secure Chemical Facilities Act, S. 3599) in the Senate on July 15.

Proponents of the IST requirement, which include unions and environmental organizations, argue that if the highest risk plant sites were made inherently safer by eliminating the possibility of a catastrophic chemical release, the facilities would become less attractive targets for terrorists.

To build support for the bill, the environmental group Greenpeace has been conducting “citizen inspections” this summer to highlight the potential risks associated with chemical plants that store and use large amounts of chlorine gas. The group’s giant green blimp flew over DuPont’s Edgemoor, Del., and Deepwater, N.J., facilities in May (C&EN, June 7, page 35), and the activists targeted Kuehne Chemical’s South Kearny, N.J., plant last month.

“The day after another attack like 9/11, no one will question whether we should have required these plants to use safer available alternatives,” says Rick Engler, director of the New Jersey Work Environment Council, a Trenton-based alliance of 70 labor, community, and environmental organizations.

But chemical manufacturers vehemently oppose any IST mandate, arguing that a government bureaucracy is in no position to adequately assess the complexity of chemical processes used at a particular facility. Industry representatives say they know best how to assess security risks and, if necessary, modify operations.

The industry instead wants the federal security initiative renewed without any significant changes, saying congressional proposals that would give DHS authority to mandate process changes are unnecessary.

IST is a “process safety tool, an engineering concept. It’s not designed to be applied to security,” said Lawrence D. Sloan, president and chief executive officer of SOCMA. “It’s brilliantly named; who can be against inherently safer technology?” Sloan remarked at a press briefing during the summit. “But the reality is not that simple.”

IST is difficult to define and characterize, and there is no agreed-upon methodology for measuring whether one process is inherently safer than another, Sloan said. “It really runs counter to the performance standards that are part of the CFATS program.”

During a panel discussion on IST, Peter N. Lodal, leader of Eastman Chemical’s plant protection technical services group, said CFATS already drives each facility to consider all possible risk-reduction options when developing a site security plan.

The reason this occurs, Lodal explained, is that the highest risk facilities face significant costs to comply with CFATS’ stringent requirements and thus have a strong incentive to implement enhancements that could reduce the facility’s risk profile and potentially move it out of regulation by the program.

“CFATS has already demonstrated its effectiveness,” he said, noting that more than 2,000 facilities once deemed “high risk” by DHS are no longer subject to the program’s regulatory requirements after adopting various security measures.

As a result, the industry is backing the Continuing Chemical Facilities Antiterrorism Security Act (S. 2996), introduced by Sen. Susan M. Collins of Maine, the ranking Republican on the Senate Homeland Security & Governmental Affairs Committee. Her bill would extend the current CFATS program for five years. It does not include an IST mandate, nor would it expand coverage to wastewater and drinking water facilities.

Keeping the existing regulatory regime in place through 2015 would allow DHS and the chemical industry to remain focused on successfully implementing the required security measures as quickly as possible, according to Sloan. “We feel that it is a very pragmatic, commonsense approach that is working well,” he remarked.

Sloan also pointed out that Collins’ bill is cosponsored by two Democrats on the homeland security panel—Sens. Mark Pryor of Arkansas and Mary L. Landrieu of Louisiana. “On the House side, we have a purely partisan bill that has received no support from the minority party,” he said.

The House passed H.R. 2868 mostly along party lines on a 230-193 vote. Twenty-one Democrats opposed the measure. “The only thing bipartisan about the House bill was the opposition against it,” Sloan said.

Several congressional aides who spoke at the summit indicated that the Senate homeland security committee would likely consider and vote on both the House-passed bill and Collins’ proposal this month.

Holly Idelson, majority counsel to the committee, said Sen. Joseph I. Lieberman (I-Conn.), the committee chairman, generally supports the House bill and does not plan to offer his own legislation. Lieberman, she noted, strongly advocates including an IST mandate in the CFATS program.

“This is too valuable to leave off the table,” Idelson said. “Sen. Lieberman agrees with the Administration that this should be part of the program. We’re not trying to set up a massive bureaucracy. Our plea would be, ‘Work with us.’ ”

Collins, however, does not believe an IST requirement is appropriate for chemical security legislation, said Brandon L. Milhorn, Republican committee staff director and chief counsel. Under the House bill, DHS would make “the final decision about what is right for your facility,” he told the audience. “Sen. Collins thinks that’s fundamentally inappropriate. It would undermine collaboration between the department and industry, particularly when we don’t have a definition of IST.”

Congress directed DHS to establish interim rules regulating security at high-risk chemical facilities as part of the department’s fiscal 2007 appropriations bill. These rules became the CFATS program. DHS’s initial authority for the program expired in October 2009 but was extended for an additional year.

With the midterm elections approaching and with a full legislative calendar, Sloan said it’s unlikely that Congress will make major changes in the program this year and will instead opt to simply pass another one-year extension. That would allow DHS to continue implementing CFATS while giving industry some regulatory certainty, he added.

Idelson pointed out that although the Administration wants Congress to permanently authorize CFATS, the White House’s fiscal 2011 budget proposal for DHS would fund CFATS through October 2011. “I would be shocked if Congress let this program lapse,” she remarked. “We do want to see it continue.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter