Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Biological Chemistry

Cellular Joy Stick

Biochemistry: Acetylation controls much more biology than previously expected

by Sarah Everts

February 22, 2010

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 88, Issue 8

Scientists have known for decades that proteins can be acetylated on their lysine residues, but the modification was long seen as the poor cousin to phosphorylation, which can activate or deactivate countless processes in living cells. New research, however, reveals that acetylation is a master switch for a who’s who of cellular functions in organisms as diverse as bacteria and humans. The widespread acetylation of important proteins will likely inspire drugmakers to target enzymes that can decorate or undress proteins with acetyl groups.

Acetylation is probably best known for its role in controlling which genes in a cell are put into deep storage and which ones can be accessed by transcription machinery. Hints of its versatility came last year, when researchers including Chunaram Choudhary, a biochemist at the University of Copenhagen, found that thousands of additional proteins are acetylated, including some involved in cell division and DNA repair.

Now, a team including Guo-Ping Zhao of Fudan University, in Shanghai, and Kun-Liang Guan, now of the University of California, San Diego, reveals that acetylation controls glycolysis, the tricarboxylic acid and urea cycles, fatty acid metabolism, and glycogen metabolism (Science 2010, 327, 1000 and 1004).“These are the fundamental pathways in a cell—how a cell gets its energy,” Choudhary says. Furthermore, such acetyl decorations cover the phylogenetic tree from bottom to top, he adds.

“Acetylation is a very elegant and accurate way for cells to respond and adapt to the energy they have available,” Zhao explains. For example, the research team found that acetylation enables bacteria to switch between glucose and citrate energy pathways, and human liver cells to switch between glucose and amino acid ones.

As researchers begin to see acetylation as a rival to phosphorylation, they will have to figure out how these two cellular control switches work in concert, Choudhary adds.

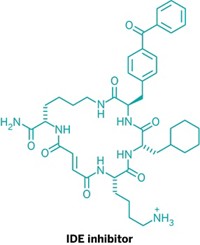

Drugmakers targeting acetylation-modifying enzymes will also encounter the same difficulties they did back when they began targeting biologically important kinases and phosphatases, says Stuart L. Schreiber, a chemical biologist at the Broad Institute, in Cambridge, Mass. Merck & Co.’s vorinostat, a treatment for T-cell lymphoma and the only FDA-approved drug that targets acetylation-modifying enzymes, faced challenges because of poor selectivity, Schreiber notes. Similarly, early attempts to design drugs against phosphatases and kinases “were fraught with complicating side effects and toxicity,” he adds.

Yet just as chemists have had success designing more specific drugs against phosphorylation-modifying enzymes, it might also be possible to develop drugs for specific acetylation-modifying enzymes, Schreiber says, noting his group’s discovery of the small molecule tubacin, which targets a single deacetylase.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter