Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Environment

Challenges To Water Reuse

ACS Meeting News: Projects to recycle wastewater face not only scientific but also economic and social hurdles

by Michael Torrice

April 25, 2011

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 89, Issue 17

A fading, decades-old photo illustrates California’s ongoing water woes. It shows a man standing next to a telephone pole in the San Joaquin Valley, the agricultural backbone of the state. He’s marked the pole with signs at different heights, each sign indicating where ground level sat in a particular year. The one at the very bottom reads “1977,” and one about 30 feet up the pole reads “1925.”

What made the ground drop almost 30 feet in five decades? The culprit is groundwater overdraft, when communities pump more water from a groundwater basin than rainfall and other sources can replenish. Farming communities in the San Joaquin Valley pumped so much groundwater that the region’s aquifers began to compress and the soil above them collapsed, lowering the ground level.

Although the valley has reined in its groundwater pumping, overdraft is still a problem across the state. The California Department of Water Resources estimates this yearly deficit at as much as 650 billion gal of water. “It’s like drawing down your savings account,” says Richard G. Luthy, an environmental engineer at Stanford University. “Eventually you’re going to get to zero.”

But groundwater isn’t the only water source at risk. Scientists expect climate change to bring longer droughts to Southern California and to shrink snowpack in the Sierra Nevada Mountains, a major water source for the state.

To stabilize the state’s water supplies, environmental engineers point to recycling wastewater as one possible solution. By purifying wastewater to irrigate crops or replenish groundwater basins, local communities can decrease their dependence on importing water from across the state or depleting local aquifers.

Currently, California recycles about 200 billion gal of water per year, according to the State Water Resources Control Board, and the state plans to reach 325 billion gal by 2020. At last month’s American Chemical Society meeting, in sessions within the Division of Environmental Chemistry, Luthy and other environmental engineers discussed the economic and social barriers that stand in the way of local water reuse projects, as well as some possible solutions.

Although Luthy acknowledges the need for more scientific research on water reuse, such as developing methods to detect and remove new classes of contaminants from wastewater, he thinks that large engineering projects also face economic and social policy issues that need to be studied. So he stepped outside his lab and decided to look into the successes and failures of local water agencies to understand what drives or stalls water reuse projects.

Luthy and his graduate student Heather Bischel worked with social scientists to develop an online survey for managers at 134 water agencies in northern California. The survey included questions about when the agency started its reuse project, what it used the treated water for, and what challenges the agency faced during the planning and development.

Of the 71 water agency managers who responded, about 90% listed a money-related issue as a challenge they faced. These hurdles included capital costs for the treatment facility, the cost of constructing pipelines to and from the facility, and determining who would pay for the treated water.

The fact that costs were a major challenge isn’t surprising, according to Y. Jeffrey Yang, a scientist at the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and coorganizer of the water reuse symposium. Recycling water is an energy-intensive process, which pushes costs up, he said. To lower water reuse’s ticket price, engineers must develop new technologies to make the process more energy neutral, he added.

But Luthy was interested in how some agencies overcame the cost problem, especially the issue of who pays for the water. When the community directly receiving the recycled water is too small, water prices can become prohibitively expensive, Luthy said. So agencies look for ways to spread out the costs.

For example, the Pajaro Valley Water Management Agency in Watsonville, Calif., opened a water recycling plant for crop irrigation in 2009. Because the water district sits along the coast, years of overdraft had depleted the groundwater basin to the point that salt water from the ocean had seeped in and made parts of the basin too salty for use. To reduce groundwater pumping near the coast and supply farmers with nonsaline water, the agency now transports a mix of recycled water and water from other sources to coastal customers affected by the saltwater intrusion.

But instead of asking only these customers to bear the full cost of the new facility, the agency charges customers two different rates: a higher one for those directly receiving the treated water and a lower one for anyone drawing from the basin. Because everyone using the basin’s water is part of the problem, everyone pays something to the solution, Luthy said.

After costs, the next major hurdle facing water agencies is handling the public’s perception of recycled water. About 25% of the managers surveyed by Luthy and Bischel identified this issue as a major challenge. “If you can’t address public perception, then it doesn’t matter if you can afford the project, because it isn’t going to happen,” Luthy said.

No one knows the perception problem better than Eleanor Torres, the director of public affairs for the Orange County Water District, which recycles 70 million gal of water every day. People worry about the water’s safety when they learn that its source is sewage, she told C&EN in an interview. “It’s essentially the yuck factor.”

Luthy thinks that water agencies can overcome this issue if they help their communities understand how the system works and provide transparent data on the water’s quality and safety. Torres agrees and said that gaining the public’s trust was key in the lead-up to the Orange County project.

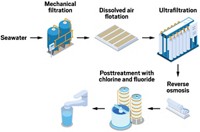

The Orange County project brings treated wastewater closer to people’s homes than the Pajaro Valley system does. In Orange County, the agency allows treated wastewater to filter into the county’s groundwater basin to replenish the water supply. This process is called indirect potable water reuse, because the treated water mixes in with the groundwater and eventually makes its way to household taps.

To bolster its customers’ trust, the agency set out to educate people on the wastewater treatment system. Agency representatives made about 1,200 presentations to community groups between 2003 and 2007. “We’d speak to anyone who would listen to us,” Torres told C&EN. Agency management enlisted people outside the agency to talk about the treatment technology and the water’s safety, including international water reuse experts and local doctors. Also, the district now offers tours, so visitors can watch how the plant works.

Luthy also stressed that agencies should explain the community’s need for water recycling. From responses to his survey, he thinks that projects succeed more often when agencies engage their entire community and explain these issues openly. “When the whole community understands the need and shares in the outcome,” he said, “the project seems to move forward.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter