Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Biological Chemistry

A Most Important Meeting

Biochemistry: A sugar that coats the human ovum and is recognized by sperm may help explain the first steps of fertilization

by Sarah Everts

August 29, 2011

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 89, Issue 35

Life’s most important rendezvous occurs between a sperm and an egg, and scientists have long debated precisely how this get-together occurs.

Now, researchers based in England, China, Taiwan, and the U.S. have identified a sugar, located on a human ovum, that is recognized by human sperm (Science, DOI: 10.1126/science.1207438). The identity of the sugar, called sialyl Lewisx, is an essential piece of information required to unscramble the biochemical steps taken during fertilization and may lead to a better understanding of infertility and better treatments for it, says Anne Dell, the biochemist at Imperial College London who led the research.

In particular, with the precise knowledge of a human ovum’s carbohydrate structure, researchers will be more likely to find the protein on human sperm that recognizes the sugar, comments Luca Jovine, an X-ray crystallographer who studies fertilization-related proteins at Karolinska Institute in Stockholm.

The work is also “a real technical achievement,” comments Pablo E. Visconti, who studies fertilization at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. Human egg samples, he explains, are so rare that it’s hard to get enough samples to study low-volume components of fertilization biochemistry.

Like the eggs of many other animal species, human ova are dressed in a thick protective coat of proteins and sugars called the zona pellucida (ZP). The particular proteins and sugars differ with the species.

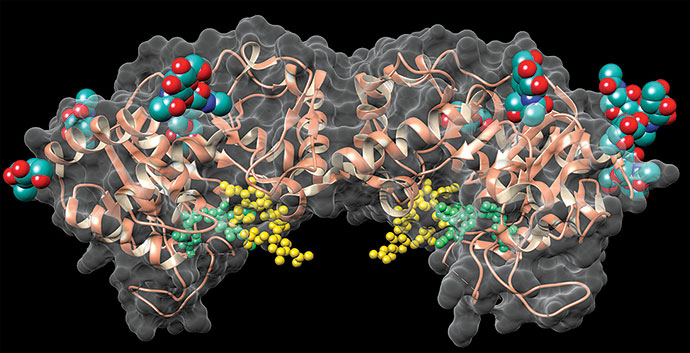

When Dell and her colleagues, who include the University of Missouri’s Gary F. Clark and the University of Hong Kong’s William S. B. Yeung, went looking for the identity of the sugary antennae located on ZP proteins, they found that the carbohydrate surface of human ZP was covered in sialyl Lewisx. This tetrasaccharide has an N-acetylglucosamine base that branches to a fucose on one side and to galactose and N-acetylneuraminic acid on the other.

The team confirmed that sperm recognize the sialyl Lewisx sugars on the egg by showing that sperm-egg binding could be inhibited when the sialyl Lewisx sugar was cloaked by antibodies. They also showed that sperm previously exposed to sialyl Lewisx sugars couldn’t bind well to eggs, presumably because the sperm protein was already occupied with sialyl Lewisx.

The researchers found that sialyl Lewisx is one of the very few sugars found on human egg cell surfaces. “This was a big surprise for two reasons,” Dell says. First, mouse ova have a diverse mix of terminal sugars, and one would have suspected that the sugars on human eggs would be equally diverse, if not more so, instead of less. Second, sialyl Lewisx is already known to scientists. The sugar is involved in helping white blood cells exit the bloodstream to get to infected tissue, but it is typically “only a very minor constituent on egg cells,” Dell says.

The blood-capillary proteins that recognize sialyl Lewisx moieties on white blood cells leaving the bloodstream don’t recognize an ovum’s exterior. Nevertheless, Dell says the sperm proteins that recognize sialyl Lewisx on egg surfaces will likely be similar to the capillary proteins.

Finding this sperm protein will provide “essential proof” that the sperm-egg recognition required for fertilization takes place by means of sialyl Lewisx, Visconti says. He points out that a competing fertilization theory, based on genetic studies, proposes that a sperm recognizes the overall macromolecular structure of the egg’s protective coating.

There’s also a chance that both theories are correct, Jovine says. “I wouldn’t be surprised if evolution has introduced a bit of redundancy into the fertilization process” to ensure survival of the species.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter