Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Environment

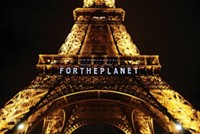

Forging Ahead On Climate Change

Emissions: Talks in South Africa seek path toward a new treaty that includes the U.S. and China

by Cheryl Hogue

November 28, 2011

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 89, Issue 48

Negotiators from around the world today begin two weeks of United Nations talks in Durban, South Africa, on curbing greenhouse gas emissions. They will also be bracing the world for the worsening impacts of climate change, which are detailed in a recently released UN report.

The negotiators’ agenda includes two intertwined items. The first is extending portions of the Kyoto protocol that require 37 industrialized countries to ratchet down their greenhouse gas emissions. The second is considering the possibility of negotiating a new global climate pact that includes emission controls for the U.S. and China.

If nothing replaces the expiring Kyoto commitments, there will be no internationally binding controls on emissions anywhere in the world. Under the Kyoto protocol, the European Union, Japan, Canada, and other industrialized nations agreed to collectively lower their emissions 5% from 1990 levels over the five-year period from 2008 to 2012. The U.S. Congress has rejected this accord.

The U.S., historically the world’s largest emitter, has long said that it will not agree to international, binding cuts in emissions unless China does the same. China recently surpassed the U.S. as world leader in greenhouse gas emissions, and it has spurned any suggestion to sign up for binding controls on its releases.

The EU is offering a plan to move forward in Durban, says Jennifer L. Morgan, director of the climate and energy program at the World Resources Institute, an environmental think tank. The EU suggests extending commitments for Kyoto protocol parties on the condition that governments agree to hammer out a new climate treaty that includes commitments from the U.S., China, India, Brazil, and South Africa. The latter four countries have rapidly growing emissions.

In recent months, China has indicated that it might agree to emission limits, says Alden Meyer, director of strategy and policy for the Union of Concerned Scientists. Such a move could encourage India to relax its resistance to participating in a new climate deal that covers emerging economies, he says. Brazil and South Africa, for their part, already seem amenable to emission control commitments.

Negotiators in Durban are also scheduled to hash out details of agreements struck last year on funding to assist developing countries in adapting to the effects of climate change and adopting low-carbon-emitting energy technologies.

Meanwhile, in a fitting preface to the Durban meeting, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change released a report focusing on the risks from extreme weather events due to climate change. The report predicts longer and more frequent heat waves, more drought, more frequent bouts of heavy precipitation that can lead to floods, and more intense hurricanes over the next 100 years.

It’s virtually certain that extreme daily maximum temperatures will happen more often while extreme daily minimum temperatures will decrease in frequency, the report says. Heat waves are at least 90% likely to happen more often and last longer, it continues.

Heavy precipitation is likely to increase over much of the world, according to the report. The report defines “likely” to mean a probability of at least 66%.

The report also says that the average maximum wind speed of hurricanes—a measure of a storm’s intensity—is also likely to increase over the next century. The number of these storms, however, will either decrease or remain unchanged, it says.

Also just before the Durban meeting, the World Meteorological Organization issued a report detailing the rapid growth of greenhouse gases accumulating in the atmosphere.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter