Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Policy

Law Completes 2012 Federal R&D Funding

Science-related programs at DOE, NIH, EPA get appropriations for fiscal year ending on Sept. 30

by Britt E. Erickson , Cheryl Hogue , Jeff Johnson

January 9, 2012

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 90, Issue 2

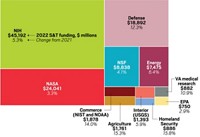

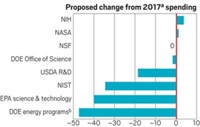

Under sweeping appropriations legislation enacted last month, research programs at the Department of Energy and the National Institutes of Health face essentially flat funding for 2012, which runs through Sept. 30. Meanwhile, research efforts at the Environmental Protection Agency must contend with budget cuts.

The new law funds most of the federal government for 2012. Congress formed this omnibus statute by combining nine separate appropriations bills that were supposed to be passed before Oct. 1, 2011, when fiscal 2012 began. Other agencies with R&D budgets—such as the National Science Foundation, the National Institute of Standards & Technology, the National Aeronautics & Space Administration, and the Department of Agriculture—received fiscal 2012 funding through a law enacted in November 2011 (C&EN, Dec. 12, 2011, page 22).

Congress’ overall funding of DOE for 2012 is $25.7 billion. This amount is 13% less than the $29.5 billion the Obama Administration proposed, but similar to levels Congress gave for the full department in fiscal 2011.

Exact comparisons of funding levels for specific programs in 2012 versus 2011 are difficult because Congress provided 2011 appropriations in six pieces of stopgap legislation before finally clearing an appropriation law to fund the federal government. Many of the temporary funding measures contained slight modifications to government program funding, and accounting for them is complex.

For the DOE Office of Science, the 2012 appropriation is $4.9 billion, which is comparable to last year’s appropriation but short of the President’s request of $5.4 billion. House of Representatives and Senate conferees who hammered out the final version of the funding legislation also called for several science-related reports. Among them is a performance ranking of all multiyear research projects in the Science Office, including DOE-funded projects in universities, national labs, energy hubs, and energy frontier research programs.

Among key chemistry-related Science Office programs, basic energy sciences receives a 3.5% increase over fiscal 2011 to $1.7 billion; fusion energy sciences, a 5.6% decrease to $402 million; and advanced scientific computing research, a 12.2% increase to $442 million. Funding of biological and environmental research grows by 1.3% to $612 million.

The Advanced Research Projects Agency-Energy (ARPA-E) program gets $275 million for project funding, with $20 million set aside for program direction. The Administration had sought $550 million to fund advanced, innovative energy projects for this program.

The conferees also ordered the energy secretary to prepare within six months a report detailing how DOE will expand several successful ARPA-E features to all department programs. These features include what the conference report calls a “rigorous” project review process, expedited contract and grant negotiations, and an “agile and innovative workforce.”

For several energy research programs, Congress slashed funding far below levels the Administration sought: Solar energy is funded at $290 million, but President Barack Obama asked for $457 million. Geothermal receives $38 million, but the President wanted $101 million. Biofuels R&D gets $200 million, but Obama requested $340 million. Support for building energy technologies is $220 million, half of the President’s request. Funding of industrial technologies is $116 million, just a third of what the President proposed.

Congress gave nuclear energy R&D $452 million, slightly more than Obama’s request and similar to 2011 levels. Fossil energy research receives $534 million, some $50 million more than the President’s request and $100 million more than last year’s level. Most of these funds are for coal-related R&D.

The conferees provided no new funds for DOE’s loan guarantee program, which has been under intense scrutiny in the House in light of the failure of solar energy manufacturer Solyndra. Obama had sought slightly more than $1.0 billion for loan guarantees, and House and Senate bills proposed some $200 million. Conferees rejected both, providing only $38 million to administer existing DOE loan activities.

Energy-related policy provisions attached to the appropriations law include one that blocks DOE enforcement of lightbulb energy efficiency standards, which were part of the Energy Independence & Security Act of 2007. On the other hand, another provision requires recipients of DOE grants greater than $1 million to upgrade the efficiency of their facility lighting to meet or exceed standards spelled out in the 2007 law.

NIH fared better than many other parts of the government. NIH receives $30.7 billion for 2012, which is $300 million or 1.0% more than its 2011 funding. The increase is well below the biomedical inflation rate, which is estimated at 3.4% for 2012, and 2.3% less than President Obama’s request.

The 2012 budget provides funding increases of 0.5% for each of NIH’s institutes and centers, except the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS), the top NIH institute for support of chemical research. NIGMS’s funding gets a 2.6% raise, most of which will go to NIH’s Institutional Development Awards program, which NIGMS now oversees.

The program aims to broaden the geographic distribution of NIH grants by funding investigators at institutions in states with historically low success rates for NIH grants. It gets an extra $46 million this year to develop infrastructure for clinical and translational research. The program was previously overseen by NIH’s National Center for Research Resources (NCRR). The center was eliminated in the 2012 budget to make room for the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), a new center focused on accelerating the pace of drug development.

Various NCRR programs are being distributed throughout NIH, with the biggest pieces going to NIGMS, NCATS, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging & Bioengineering, the National Institute on Minority Health & Health Disparities, and the Office of the Director. The transfer of money from NCRR to these institutes is reflected by gains in their 2012 budgets.

The 2012 budget provides a total of $576 million for the launch of NCATS. Of that money, $10 million will fund the Cures Acceleration Network, a new program authorized under the health care reform act of 2010. This program is receiving funding for the first time, but the amount is far less than President Obama’s request of $100 million. Along with the funding for the network, Congress requested that NCATS charter an Institute of Medicine (IOM) work group to help identify ways to accelerate the development of new drugs and therapies.

The biggest part of NCATS’s budget, $488 million, will go to the Clinical & Translational Science Awards. The five-year-old program, formerly overseen by NCRR, aims to speed up the translation of basic research into medical treatments, engage communities in clinical research, and train clinical and translational researchers. Congress urged NIH to support an IOM study to evaluate the program and determine whether changes to its mission are needed.

NIH’s Therapeutics for Rare & Neglected Diseases also moved to NCATS. The program, which was previously administered by the National Human Genome Research Institute, will receive $24 million in 2012.

NCATS has two goals: to identify bottlenecks in the drug development process that are amenable to reengineering and to develop technologies and methods to streamline the process. Congress made it clear in the 2012 appropriations law that NCATS should complement, not compete with, the private sector. Lawmakers directed NIH to host a workshop this year with key research organizations, venture capitalists, the pharmaceutical industry, the Patent & Trademark Office, and the Food & Drug Administration to help speed up commercialization of new therapies.

Congress also instructed NIH to ensure that the percentage of funds used to support basic research is maintained and that the number of research grants issued in 2012 remains at the same level as in 2011. Although the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology recommended that NIH receive $35.0 billion in 2012, the group welcomes the slight increase that NIH received. “We wish it could have been more, but we are very grateful that there was any kind of an increase in this budget environment,” says Jennifer Zeitzer, the federation’s director of legislative relations. The group is urging Congress to provide NIH with bigger increases in the future, at least keeping pace with biomedical research inflation.

Congress earmarked $1 million in the budget of the Department of Health & Human Services to support a National Academy of Sciences (NAS) review of the listing of formaldehyde and styrene in the 12th Report on Carcinogens (RoC). The congressionally mandated document is prepared by the National Toxicology Program, an interagency program that includes NIH’s National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, the National Institute for Occupational Safety & Health of the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, and FDA’s National Center for Toxicological Research.

The chemical industry claims that the evidence for listing formaldehyde and styrene is insufficient. The American Chemistry Council (ACC), a trade association, and the Styrene Information & Research Center, which represents the styrene industry, fought for years to keep the chemicals off the list. The groups pressured Congress to require an NAS review of the evidence for listing the chemicals as carcinogenic.

“By requiring a thorough scientific peer review by NAS of the formaldehyde and styrene sections of the 12th RoC, Congress has ensured that accurate, credible information about these two widely used chemicals will be communicated to the public,” ACC President and Chief Executive Officer Calvin M. Dooley said in a statement.

EPA’s modest research program did not fare as well as those of DOE and NIH. Congress provided only $795 million for the agency’s science programs in 2012, down 6.0% from the 2011 appropriation of $846 million.

In addition, Congress rejected the President’s request of $5 million in new funding for two new EPA research initiatives, one on green chemistry and another to reduce hazardous electronic waste. Congress also turned down Obama’s call for an additional $3 million to improve monitoring of toxic air pollutants emitted from industrial sites including chemical plants.

Congress did, however, provide funds for an EPA study on whether hydraulic fracturing to extract natural gas leads to pollution of drinking water wells, despite political rumblings against this research effort. Known as fracking, this drilling method uses water and chemicals under pressure to free natural gas from shale. Many Republicans in the House have criticized EPA for taking on the fracking study, which they argue is unnecessary. A Democrat-controlled House in 2010 recommended the research.

As part of the 2012 funding law, Congress imposed new policy requirements on the Integrated Risk Information System (IRIS), EPA’s program that assesses chemicals’ hazards. The assessments often face a barrage of criticism. Although they aren’t regulations, the analyses include EPA scientific judgments of what a safe dose of a chemical is. Regulators rely on those judgments as they set standards for pollution control and cleanups.

Last year, in a report critical of EPA’s pending assessment of formaldehyde, NAS gave EPA unsolicited recommendations for ways to improve chemical assessments. EPA has begun to implement those recommendations, yet IRIS continued to catch flak from Republicans in the House during hearings in the second half of 2011 (C&EN, Oct. 24, 2011, page 32).

The new appropriations law requires EPA to document how it has addressed each NAS recommendation for every draft chemical assessment the agency releases in 2012.

“The changes called for by NAS and now required by Congress will not only improve the quality of science used by EPA, but will also provide for much needed transparency and objectivity in the program,” says ACC’s Dooley. For years ACC has found fault with how EPA conducts the assessments.

Advertisement

However, Congress failed to address NAS’s bottom-line recommendation that EPA not delay completion of pending chemical assessments, says Rena I. Steinzor, president of the Center for Progressive Reform, a liberal-leaning think tank. “That message has now gotten lost in the shuffle,” she tells C&EN.

The appropriations statute also requires NAS to review EPA’s pending hazard assessment of inorganic arsenic, which contaminates some drinking water supplies in the U.S. West. In addition, the law requires NAS to choose up to two other EPA draft chemical assessments to review.

Now that the dust has settled on the 2012 funding debate, agencies are busy finishing a budget proposal for fiscal 2013, which starts on Oct. 1. The Administration will release that proposal next month, and Congress will begin debating it soon.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter