Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Policy

Data Snarl

EPA wants some information submitted for REACH, but companies say they can’t share the information

by Cheryl Hogue

May 28, 2012

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 90, Issue 22

The Environmental Protection Agency and some U.S. chemical manufacturers appear caught in a standoff that involves the European Union. The companies have provided toxicity data for some of their products to the EU under the Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation & Restriction of Chemical Substances (REACH) law. Now, EPA is asking these companies for the same information they provided to the EU. But the firms say they can’t legally deliver it.

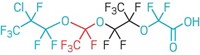

This issue is coming to a head around an October 2011 proposal from EPA that would require makers of 23 high-production-volume (HPV) chemicals to generate basic toxicity data for their products. Substances made commercially in amounts of at least 1 million lb per year are designated HPV.

In the proposal, issued under the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA), the agency said it wants the information because there is or may be substantial human exposure to the 23 compounds. The agency also said it has insufficient data to determine the effects of those chemicals on human health or the environment.

The move is part of EPA’s effort to complete data collection for HPV chemicals. Manufacturers voluntarily are supplying—or have submitted—toxicity data on more than 1,800 HPV compounds under a partnership launched in 1998 by EPA, the advocacy group Environmental Defense Fund (EDF), and the chemical industry. Meanwhile, the agency has been pursuing toxicity data for more than 100 other HPV substances for which companies have not volunteered to provide information.

The agency has turned to regulations under TSCA to obtain the information on those remaining chemicals. In recent years, EPA has issued three rules requiring toxicity testing of 63 of those substances. If finalized, the 2011 proposal would be the fourth rule requiring the generation of basic toxicity data for HPV substances.

Makers of a dozen of the 23 substances targeted for testing in the 2011 proposal have registered or preregistered these chemicals under REACH, said Joseph Manuppello, a research associate at People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals, at a public meeting on the proposal that EPA held on May 16. That means companies have supplied basic toxicity data on these compounds to the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) or are likely to be conducting tests to generate the information, he said.

But in some cases, chemical makers won’t supply the data they submitted for REACH registration to EPA. Firms may be stopped by legal agreements from sharing this information, Kelly A. Magurany, a senior toxicologist for chemical producer Nalco, a division of Ecolab, said at the meeting.

Under REACH, manufacturers that produce the same chemical formed coalitions called Substance Information Exchange Forums to share the cost of generating the toxicity data needed to register a substance. In many cases, the participating firms entered into contracts specifying that they will use the information for REACH purposes only.

These contractual provisions are designed to protect the companies that paid for the data. For instance, Magurany said, if the full studies for a substance are provided to EPA, a competitor who wishes to register that chemical under REACH might obtain the data from EPA through the Freedom of Information Act. This would allow them to register without sharing the cost of conducting the studies, she asserted.

Magurany and Manuppello urged EPA to accept, in lieu of full testing data, robust summaries of the studies used for REACH registration. Under REACH, chemical manufacturers must supply robust summaries to ECHA to register substances produced in annual amounts greater than 10 metric tons (22,046 lb). These documents, according to ECHA, are “a detailed summary of the objectives, methods, results, and conclusions of a full study report providing sufficient information to make an independent assessment of the study.” ECHA is posting information from these robust summaries on its website.

Christina Franz, senior director for regulatory and technical affairs at the industry trade association American Chemistry Council (ACC), said at the meeting that EPA should try to obtain robust summaries before using TSCA to require toxicity tests.

Franz also encouraged EPA to work with ECHA to develop an agreement for sharing the full studies. Although the agencies have announced they intend to work out such a deal, an ECHA official recently said this would not be a quick process. Even if the two agencies struck an agreement, further approval from the EU would be needed before ECHA could share this protected information with EPA (C&EN, March 12, page 46).

Magurany said if EPA finalizes the proposal, Nalco, which makes at least one of the 23 chemicals targeted by the rule, may end up conducting expensive new tests that duplicate studies done for REACH registration. EPA would hurt companies’ global competitive advantage by putting them in this position, she said.

“This is just utterly unbelievable,” Richard A. Denison, a senior scientist with EDF, tells C&EN. Companies are telling EPA not to bug them for information on their products but to get it from ECHA, he says.

The data-sharing contracts for REACH were not required and were privately negotiated by companies, Denison points out. “That’s their problem. They created it and they need to solve it. It’s not a reason why EPA or the public should forgo having access to this information.”

At the public meeting, ACC’s Franz and Deborah Howell, a product chemist in the regulatory department of Nalco, took issue with part of EPA’s 2011 proposal that would, in addition to requiring tests on 23 chemicals, regulate 22 other HPV substances whose makers have not volunteered to produce toxicity data.

This part of the proposal would require firms to file a notice with EPA before making or processing any of the 22 chemicals in any amounts for any use or combination of uses that is likely to expose at least 1,000 workers at a single corporate entity. This notice, the agency said in the proposal, “would provide EPA with the opportunity to evaluate the intended use and, if necessary, to prohibit or limit that activity before it occurs.”

Howell said that EPA generally invokes this authority—called a significant new-use rule—shortly after a company, as required under TSCA, has informed the agency that it is planning to commercialize a chemical.

She and Franz suggested that instead of issuing a significant new-use rule, EPA use its TSCA authority to require makers of the 22 substances to provide general information—such as production, use, and human exposure data—for these products.

EPA officials did not respond to the comments at the public meeting. Generally, the agency replies to points raised about its proposals when it issues final rules. ◾

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter