Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Spectroscopy

First Fluorine Gas Found In Nature

Analytical Chemistry: Researchers resolve long-debated stink from a fluorite mineral

by Deirdre Lockwood

July 16, 2012

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 90, Issue 29

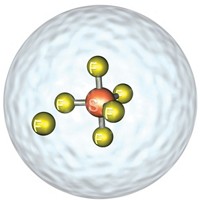

Fluorine gas (F2), which has been called chemistry’s hellcat, is so reactive that chemists have long assumed it does not occur in nature. Now researchers in Munich have evidence that the gas exists naturally, trapped inside a dark purple fluorite mineral called antozonite (Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., DOI: 10.1002/anie.201203515).

The discovery resolves a nearly 200-year-old debate about why the mineral, known as “stinkspar” or “fetid fluorite,” smells so bad when it is crushed. Since antozonite was documented in 1816 as making fluorite miners in Bavaria sick to their stomachs, chemists have blamed the stench on several compounds, including I2, Cl2, and ozone. F2 was suspected as the smelly component in 1891 by the French scientist Henri Moissan, who later won the Nobel Prize for isolating the element. But many chemists at the time responded that “it can’t be true,” says Florian Kraus, a fluorine researcher at the Technical University of Munich.

Kraus and collaborators, including Jörn Schmedt auf der Günne of Ludwig Maximilian University, have found the first in situ evidence that F2 is the culprit. After grabbing samples of antozonite from beside the highway in Wölsendorf, Germany, near the area that once made miners sick, they analyzed pea-sized chunks with solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance spectrometry. The technique allowed them to detect fluorine gas inside the rock without breaking it open.

“This is the first time fluorine gas has been characterized in nature,” says Alain Tressaud, research director emeritus at the French National Center for Scientific Research in Bordeaux. “It is a fundamental result.”

The researchers propose that natural uranium deposited in the mineral reacts with fluorite as it decays, generating species that combine to form fluorine gas, which is trapped in the mineral matrix. Calcium clusters formed in the process create the mineral’s dark color.

So what is the telltale smell like? Tressaud says it is fitting that a Frenchman first isolated fluorine, because “it has a garlic-type smell.” Schmedt auf der Günne begs to differ: “At high dilution,” he says, “it’s like a perfume.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter