Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Physical Chemistry

New Details On Water Hexamer Structures

Simulations detail the interplay of hexamer cage, prism, and book shapes that make up the smallest drops of water

by Jyllian Kemsley

July 23, 2012

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 90, Issue 30

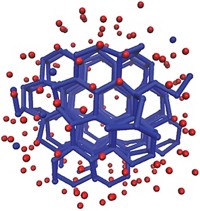

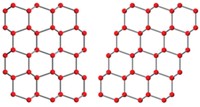

A quantum mechanical study has shed more light on the hexamer structures that make up the smallest drops of water—that is, the clusters with the fewest number of water molecules capable of holding a three-dimensional shape via hydrogen bonding (J. Am. Chem. Soc., DOI: 10.1021/ja304528m). The hexamer is the prototypical system scientists use to understand the structure and dynamics of bulk water. Yimin Wang and Joel M. Bowman of Emory University and Volodymyr Babin and Francesco Paesani of the University of California, San Diego, studied the clusters through simulations. They found that the “cage” and “prism” structures exist in almost equal amounts at temperatures near absolute zero. As the temperature increases to 60 K, more of the cage structure forms. A third structure—the “book”—appears at warmer temperatures. Interplay between energetic and entropic effects drives the differences in cluster species population, with entropy favoring the floppier cage and book clusters, Paesani says. The minute energy differences between the structures make them particularly sensitive to their environment, the researchers say, which may explain different amounts of the structures observed for different carrier gases in supersonic expansion experiments on water clusters reported earlier this year (C&EN, May 21, page 33).

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter