Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

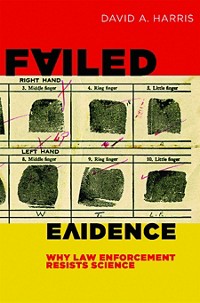

Forensic Science

Challenges Of Forensic Science

August 6, 2012

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 90, Issue 32

Perhaps I’m quibbling, but in the practice of law (as with chemistry), using the proper term may be very important. Although the meaning of “forensic” (noun) may be changing, most dictionaries still list the first meaning as “the study of argumentation and formal debate.”

“Forensic science” would be “the application of science to questions of law.” The definition in Wikipedia, however, points out a broad spectrum of sciences that may be applied to legal questions. In fact, there are currently 11 different sections in the American Academy of Forensic Sciences.

Aside from brief mention of bite mark analysis and questioned document analysis, “Still Seeking Forensic Reform” (C&EN, June 25, page 32) is really about a subset of the forensic sciences, “criminalistics” (not to be confused with “criminology,” which deals not with the physical sciences but with the social sciences).

Although I agree with Jay Siegel that there is a need for research that would provide a more solid scientific basis for many of the types of examinations performed by “criminalists,” I feel the article in C&EN as well as the National Research Council report paint an unfair and overly pessimistic picture of the current state. For those readers who would appreciate a more balanced view, I highly recommend “Scientific Principles of Friction Ridge Analysis & Applying Daubert to Latent Fingerprint Identification” by Thomas J. Ferriola (although the article deals with fingerprints, the same reasoning may be applied to other areas of criminalistics). This article was first printed in the Criminal Law Bulletin but can be found online at www.clpex.com/Articles/ScientificPrinciplesbyTomFerriola.htm.

By Robert D. Blackledge

El Cajon, Calif.

The informative article “Still Seeking Forensic Reform” well describes many problems in data obtained by forensic analysis and the work of medical examiners. As a former district medical examiner in Florida and longtime consultant to medical examiners, I applaud the effort to bring quantitative measures to the field.

At the same time, an even more fundamental problem is not discussed in the article: accounting for the pathogenesis and physical presentation of natural conditions that mimic common findings of trauma in cases of death from uncertain causes. One cannot dispute a clear bullet pathway in the brain or through the heart with the expected findings at autopsy.

In the realm of alleged child abuse, however, the equation “bleeding or contusion = criminal abuse or trauma” is too often a leap to judgment, setting into motion subsequent care for the injured and interpretation of the pathological findings later. I have yet to see a case of alleged shaken baby syndrome in which the medical examiner took the time to dissect the upper cervical spinal column to determine whether there was in fact resultant injury at the key site.

Similarly, meningitis is often missed both in emergency rooms and at autopsy. Slowly maturing infants born more than a few weeks early will commonly have healing lesions along the margins of the cerebral ventricles that rebleed spontaneously. Very immature infants are occasionally deficient in ascorbic acid, which leads to such hemorrhages.

The better known tendency of children with osteogenesis imperfecta to develop fractures from even the loving hugs of a parent is simply the tip of the iceberg of an inadequate application of what is known about the spectrum of findings consistent with and fully explained by a deeper understanding of natural disease.

This failure has an impact on civil litigation as well. I recall the case of an obstetrician whose medical license was challenged prefatory to a suit for damages because of massive uterine hemorrhage during delivery, with stillbirth the result. Fortunately, both the placenta and the fetus were critically examined: There was a subclinical state of lupus with thrombocytopenia that determined the outcome—rapid delivery for fetal distress notwithstanding. The challenge failed, and no suit was brought.

Another aspect of these things should also be addressed: Forensic experts need to take the time to carefully explain to family and friends of the deceased what actually happened when study of the case indicates an outcome due to natural causes.

By D. Radford Shanklin

Woods Hole, Mass.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter