Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Environment

Sand Filter Removes Estrogen With Ease

Wastewater Pollution: Inexpensive wastewater treatment might work just as well as more advanced methods to remove polluting hormones

by Naomi Lubick

April 20, 2012

Sand filtration might work as well to remove estrogen from wastewater as expensive and more technologically complex methods, according to research published in Environmental Science & Technology (DOI: 10.1021/es204590d). The findings might help protect wild fish from estrogens at low cost, researchers say.

Many scientists have found that estrogen steroids can feminize male fish at low levels, around nanograms per liter, sometimes causing the males to grow female gonads and become infertile. Such levels are typical for wastewater effluent. Sewage treatment plants around the world use a variety of methods to remove estrogens. The methods include activated carbon--whose production takes a lot of energy and releases carbon dioxide--and simpler sand filters paired with microbes that consume organic matter.

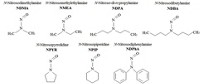

After hearing that a local utility was planning to test methods’ ability to remove estrogens, researchers led by Alice Baynes of England’s Brunel University suggested adding biological assays on fish to the planned chemical tests. Together, they sampled four wastewater streams for estrone, 17β-estradiol, and 17α-ethinylestradiol: one stream treated only with so-called activated sludge, a standard approach in most wastewater treatment plants; one treated with activated sludge followed by a sand filter containing microbes that can break down compounds; and two streams that passed through activated sludge, a sand filter, and an additional cleanup material, either granular activated carbon or oxidation by chlorine dioxide.

The researchers’ analyzed weekly samples by liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry, and expressed amounts of the sum of the three estrogens in terms of the biological activity of 17α-ethinylestradiol, the most biologically active steroid in the mix. Chlorine dioxide removed the most estrogens, with its waste stream peaking at 11.0 ng 17α-ethinylestradiol equivalents per liter. Activated sludge alone performed least well: It let through a maximum of 21.8 ng/L of the bulk estrogen equivalent. The sand filter-sludge combination did nearly as well as the chlorine dioxide treatment, letting through at most a bulk estrogen equivalent of 11.1 ng/L. When the researchers considered the average concentrations, sand filtration looked less promising: Its mean was 5.84 ng/L while chlorine dioxide’s was 1.95 ng/L.

The researchers also employed their biological assay: They exposed a native species of fish called a roach (Rutilus rutilus) to each of the waste streams. After the fish lived in the waste streams for six months, the researchers dissected them to search for signs of feminization—ovaries in male fish, for example.

The fish living in the water that had gone through sand filtration or activated carbon treatment showed no feminization at all. But some male fish living in the chlorine-dioxide treated wastewater streams had intersex gonads, despite the fact that it contained the least estrogen of any stream. The team is now looking for compounds in this treated waste that might block male hormones.

The study’s main takeaway, Baynes says, is that “sand filtration can be a cost-effective method of removing estrogen.”

The new work is important, says Beate Escher of the National Research Centre for Environmental Toxicology in Brisbane, Australia, because it shows that judgments about a treatment method’s efficacy must be made with the “whole chemical and biological story” in mind. Pairing cheap methods to remove estrogen turned out to be better for fish than a more-expensive treatment, she notes, and “an apparently better treatment process, that also happens to be more expensive, might not be necessary.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter