Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Biological Chemistry

Spinning Carbon Nanotubes Open Pores In Cancer Cells

Molecular Machines: Magnetically driven nanotube bundles make cells more permeable and kill them

by Prachi Patel

September 19, 2012

Under a rotating magnetic field, carbon nanotubes form spinning bundles that drill into cell membranes, researchers have discovered (Nano Lett., DOI: 10.1021/nl301928z). The technique could create pores in tumor cells to destroy them or deliver drugs to them, its inventors say.

Dun Liu, a doctoral student in Alfred Cuschieri’s laboratory at the University of Dundee, in the U.K., knew that carbon nanotubes align parallel to an applied magnetic field. To test how a rotating field would affect nanotubes, he used electron microscopy to observe the nanotubes forming rotating bundles while under such a magnetic field.

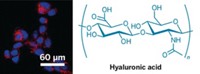

Since he knew that individual nanotubes could penetrate cell membranes, he and his colleagues wanted to investigate the interaction of the spinning nanotubes with cells. So they put nanotubes coated with a biocompatible polymer into a culture of breast cancer tumor cells along with a fluorescent dye. The researchers then took three samples of the cells and applied a rotating magnetic field, with strength of either 20, 40, or 75 millitesla, for 20 minutes.

Compared to cells in the lower fields, more cells took up the dye when exposed to higher fields: up to 25% for the 75-millitesla field. Within 24 hours of exposure to the two higher fields, about one-third of the cells died. The researchers used atomic force microscopy to find that exposure to the nanotubes and magnetic fields made the cell surfaces rough.

The researchers speculate that at 40 millitesla, the tubes drill pores in the cells that can quickly reseal, making the cells more permeable but not killing them. At even higher fields, the nanotubes might destroy the cell membranes or create larger pores, the researchers think, so that the cells’ components leak out, killing the cells.

The technique should affect healthy cells in the same way, says Cuschieri. To selectively kill tumors, he imagines using MRI to visualize a tumor so that doctors could inject nanotubes into the cancerous tissue before applying the rotating magnetic field.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter