Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Analytical Chemistry

Gold Nanofingers Could Detect Notorious Infant Formula Contaminant

Food Safety:Portable surface-enhanced Raman scattering method can detect low levels of melamine in dairy products

by Erika Gebel

October 16, 2012

In 2008, 300,000 Chinese infants became ill and six died after drinking formula intentionally diluted with the toxic compound melamine. As a result, safety agencies worldwide now routinely test milk-based products for melamine. However, the available assays are cumbersome. A new portable device that uses surface-enhanced Raman scattering to quickly detect melamine in milk and formula could make the screening process easier (Anal. Chem., DOI: 10.1021/ac302025q).

Regulators at the Food and Drug Administration use mass spectrometry to detect melamine. This process requires extensive sample preparation, expensive lab equipment, and skilled operators. Zhiyong Li and colleagues at Hewlett-Packard Laboratories turned to Raman spectroscopy, as a simpler, less expensive method that would allow workers to run tests in the field. Organic molecules such as melamine produce characteristic Raman signals when irradiated with light. Several handheld Raman spectrometers are commercially available. Also, says Peidong Yang, of the University of California, Berkeley, who was not involved in the work, a portable melamine detector would be “very useful” in developing parts of the world.

The HP method takes advantage of a phenomenon called surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS) to detect low concentrations of the contaminant. In a typical SERS experiment, researchers allow their molecule of choice to fall into nanosized gaps within metal structures. Inside these gaps, commonly called “hot spots,” the Raman signal from the chemical gets an enormous boost through interactions between the molecules and the metal.

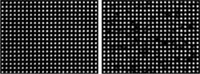

Li designed hot spots for melamine method using a 500 nm-diameter ring of five nanofingers. Each finger is a gold-tipped polymer column. These fingers can bend inward toward the center of the ring. When they do, they form SERS gaps.

The researchers tested their method on samples of milk and formula spiked with varying concentrations of melamine. To measure the melamine levels in each sample, they first used a simple dialysis method to filter out large molecules, such as milk proteins. Next, they applied the purified sample to a 5 by 5 mm chip imprinted with the nanofinger sensors and let the sample dry. This drying process produces surface tension that pulls together the tips of the nanofingers in each ring. The researchers then inserted the chip into a house-made portable Raman spectrometer and looked for melamine’s signature peaks. Based on the signal’s intensity, they could determine the melamine concentration.

The method’s limit of detection is 100 parts per billion in infant formula and whole milk, which is well below the safe limit set by the FDA, 1 part per million.

Martin Moskovits of the University of California, Santa Barbara, calls the development of the detector “a very nice piece of work.” He thinks that the method could detect a wide range of other molecules at low concentrations, such as environmental pollutants and explosives.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter