Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Safety

Fertilizer Blast Ignites Concerns

Congress will look at how chemical facilities are regulated in aftermath of Texas disaster

by Glenn Hess

May 27, 2013

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 91, Issue 21

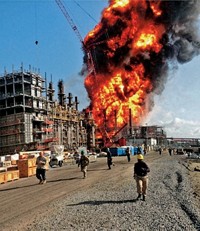

The catastrophic explosion at a fertilizer depot in Texas last month is raising new questions about the effectiveness of the federal government’s program to ensure the security of plants that handle large amounts of extremely dangerous industrial chemicals.

Some Democratic lawmakers are suggesting that the disaster has exposed major flaws in the Department of Homeland Security’s (DHS) Chemical Facilities Anti-Terrorism Standards (CFATS) program. The nearly six-year-old initiative is designed to safeguard facilities that produce, store, or use hazardous chemicals that could be exploited by terrorists to inflict mass casualties in the U.S.

However, DHS has struggled to get the program off the ground. The office that administers CFATS has had eight directors since 2006, and this leadership turnover has “contributed to poor decision-making by staff, significantly slowing progress,” the department’s inspector general said in a March report.

Critics have also charged that the program lacks teeth because Congress did not give DHS the authority to require chemical facilities to adopt safer practices, such as switching to less toxic chemicals or reducing the amount of hazardous substances stored on-site.

Rep. Bennie G. Thompson of Mississippi, ranking Democrat on the House of Representatives Committee on Homeland Security, notes that DHS was not regulating the West Fertilizer Co. facility—and that fact calls into question the fundamental value of the CFATS program. “This facility was known to have chemicals well above the threshold amount to be regulated under CFATS, yet DHS did not even know the plant existed until it blew up,” Thompson remarks.

But other members of Congress say it’s too soon to consider making changes in any regulatory program. The Senate Homeland Security & Governmental Affairs Committee “will examine the impact of existing federal safety and security regulations on facilities like West Fertilizer and seek to identify whether additional steps should be taken to protect the public,” says a spokeswoman for Sen. Thomas R. Carper (D-Del.), committee chairman.

CFATS BY THE NUMBERS

The Department of Homeland Security has reviewed more than 44,000 preliminary assessments from facilities with chemicals of interest.

4,351 facilities have been determined to be high risk and are currently covered by CFATS.

More than 3,000 facilities voluntarily removed, reduced, or modified their holdings of chemicals of interest and are no longer deemed high risk.

1,242 visits by DHS to assist facilities with CFATS compliance.

380 security plans authorized by DHS.

85 security plans approved by DHS after an on-site inspection.

SOURCE: DHS

The April 17 explosion at the West Fertilizer storage and distribution facility in the small farming town of West, 18 miles north of Waco, killed 15 people, injured more than 200, and destroyed dozens of homes. Investigators have determined that ammonium nitrate caused the explosion, but what triggered a fire that led to the blast remains undetermined.

Investigators say a fire began in a building called the seed room, causing an estimated 28 to 34 tons of nearby ammonium nitrate to explode. About 150 tons of the chemical was on-site at the time, including 100 tons in a railcar that did not explode.

Ammonium nitrate is mostly used as an agricultural fertilizer, but it is also a component of explosives used in mining and construction. Besides its legitimate uses, the chemical has been used in devastating terror attacks, including the Oklahoma City bombing in April 1995.

Under CFATS, companies that make, use, store, or distribute any of approximately 300 “chemicals of interest” above certain threshold levels are required to file a preliminary assessment with DHS. This so-called top-screen report identifies the chemicals and quantities held on-site.

DHS uses the information as the starting point in determining whether a facility should be classified as high risk under the chemical security program. DHS has assessed top-screen submissions from more than 44,000 chemical facilities across the U.S. Most have been deemed low risk.

If a facility qualifies for regulation as a high-risk chemical site, DHS requires it to conduct a security vulnerability assessment and develop a plan that meets department-defined, risk-based performance standards to ensure site security. A total of 4,351 high-risk sites are currently subject to the requirements of CFATS.

Since ammonium nitrate is an obvious terrorist threat, fertilizer facilities must notify DHS when they possess at least 400 lb of the substance packaged as blast agent or 2,000 lb of agricultural-grade material. Although West Fertilizer was above this threshold, it did not file a top-screen report, a DHS spokesman tells C&EN. “The West Fertilizer facility is not currently regulated under the CFATS program,” he says.

Rep. Thompson says that’s a problem. “I strongly believe that had DHS personnel worked with the plant owners to identify vulnerabilities and put the proper safeguards in place, as DHS does at thousands of CFATS-regulated plants across the country, the loss of life and destruction could have been far less extensive,” he says.

A Democratic congressional aide to the Homeland Security Committee tells C&EN that most facilities “probably comply with the top-screen reporting requirement. But there is a population of facilities that ignore the law. We are pursuing the question of how DHS can better identify these ‘outliers’ and require them to submit top-screens.”

Thompson and Rep. Henry A. Waxman of California, ranking Democrat on the House Energy & Commerce Committee, have also called on President Barack Obama to appoint a special commission to examine security at the nation’s chemical facilities.

“In light of the tragic events in West, we ask you to consider steps that can be taken in response to the explosion to reduce the security risks of chemical plants, refineries, water treatment facilities, and other facilities holding large stores of industrial chemicals,” they wrote in a May 2 letter. “In particular, we urge you to establish a Blue Ribbon Commission of experts that can take a fresh look at this important issue and determine what should be done to secure these facilities.”

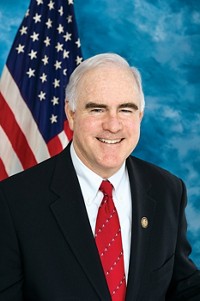

Rep. Michael T. McCaul (R-Texas), chairman of the House Homeland Security Committee, says his 32-member panel plans to examine “any gaps in oversight of security and will take appropriate action.” He has asked DHS Secretary Janet Napolitano to explain by June 3 her department’s “failure to know about the West Fertilizer plant.”

If the CFATS reporting program is ineffectual, then DHS has an obligation to fix it, McCaul told Napolitano in a letter earlier this month. “The identification of facilities at risk of terrorist infiltration is the foundation of the CFATS program,” he wrote. “DHS must reevaluate its outreach campaign to ensure that it is robust and comprehensive. Facilities which are either inadvertently or willfully off the grid—facilities like West Fertilizer—must be both aware of their requirement to report and held to account for failing to do so.”

A week after the deadly Texas explosion, Sen. Frank R. Lautenberg (D-N.J.) introduced legislation that would make it a federal crime for a company to store dangerous chemicals on-site and fail to register with DHS. Under the bill (S. 814), officers of companies that intentionally fail to complete and submit top-screen reports could face up to six years in prison.

Lautenberg is also sponsoring two bills (S. 67 and S. 68) that would give DHS new authority to require high-risk chemical and water treatment plants to either adopt safer processing technologies or switch to less toxic materials, if possible, to reduce the consequences of an accident or terrorist attack.

“We need to pass my legislation to require facilities to thoroughly review risk and help us move toward more secure plants and safer communities,” Lautenberg says. “Hundreds of plants have already switched to safer and more secure chemicals and processes, and this commonsense legislation would increase safety nationwide.”

The legislation also requires facilities to provide “appropriate information” to local emergency planning committees, law enforcement officials, and emergency responders to ensure an effective, collective response to terrorist incidents. “We may have been able to save lives in West if first responders and regulators had knowledge about the chemicals stored on-site,” Lautenberg says. This aspect of the proposal does, however, still rely on self-reporting by these small companies.

Lautenberg’s proposals are strongly backed by a coalition of environmental and labor groups. “The hazards of storing tons of ultrahazardous materials are well-known, but current safety standards do little to prevent such a disaster,” says Rick Hind, legislative director of environmental group Greenpeace. “West, Texas, is just the tip of the chemical disaster iceberg.”

Although the primary goal of Lautenberg’s legislation is to prevent an accidental toxic release, activist groups also argue that if chemical processes at a high-risk facility were safer, then the facility would be less attractive as a potential terrorist target.

The chemical industry has long opposed efforts by some members of Congress to require the use of so-called inherently safer technology, arguing that it is a complex engineering concept that is unsuited to regulation.

“These efforts have been considered and rejected by previous Congresses,” notes William E. Allmond IV, vice president of government and public relations at the Society of Chemical Manufacturers & Affiliates, a trade association for specialty chemical companies. He also notes that the existing CFATS program has “repeatedly been deemed appropriate and sufficient by congressional members in both parties in both chambers.”

Congress should refrain from judging the effectiveness of CFATS until investigators can determine what went wrong in Texas, Allmond says. “If the investigations conclude that federal regulations need to be improved, we will all be better served if Washington homes in on current laws that specifically address accident prevention, not simply look at those that address terrorist attacks,” he remarks.

The Environmental Protection Agency does focus on accident prevention through its risk-management program under the Clean Air Act. However, ammonium nitrate is not on the list of chemicals that facilities must report to the agency because it is not a toxic air pollutant.

Hind argues that the Clean Air Act gives EPA broad authority to require companies to replace dangerous chemicals with safer alternatives. “What we have now is risk management. What we need is risk prevention.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter