Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Publishing

Nine For Ninety

by Josh Fischman

September 9, 2013

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 91, Issue 36

“We offer for your approval the News Edition,” wrote the editor of Industrial & Engineering Chemistry on Jan. 10, 1923. The American Chemical Society had decided the fast-changing world of chemistry deserved a news publication to cover expanding industry, advancing technology, and the people who were making these things happen. That News Edition became Chemical & Engineering News 19 years later, in 1942.

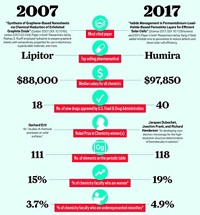

During the 90 years in which C&EN has been covering chemistry, the world within the enterprise and the world surrounding it have indeed changed. To celebrate those changes and our nine decades of publishing, we’re proud to present nine stories. Each of them focuses on an area of chemistry that has had a profound effect on the planet, often for the better, sometimes for the worse, but always transformational.

In 1923, when C&EN was launched, the world was beginning a technological speedup, with industries producing fertilizers, pharmaceuticals, and various kinds of fibers and dyes on a large scale, made possible by advances in chemical synthesis. But the science was struggling to conceptualize the thing that held these materials together: the chemical bond. The attempt to visualize and explain bonds has animated much of chemistry for the past nine decades, helping turn the discipline into a predictive science (see page 28).

During those same 90 years, another aspect of chemistry—antibiotic discovery—has also surged, but more recently its fast pace has turned into a standstill. In the middle of the 20th century, chemists helped create new classes of drugs, such as tetracyclines, which saved countless lives. But by the 1980s, discovery techniques began coming up empty, and new ones have not replaced them. Right now, the medicine cabinet is disturbingly empty of effective new antibacterials (see page 34).

Big hopes for tiny constructs is the theme of our story on nanotechnology, a field that has grown from work on semiconductor processing in the early 1970s to today’s broad endeavor that encompasses cell phones and fine-tuned medical diagnostics. But the major impact, many scientists now say, has been to spur cross-disciplinary research, pushing chemists into new collaborations with researchers they hadn’t worked with before (see page 38).

Chemists’ efforts to visualize proteins at an atomic resolution have laid the foundations for structural biology. This work has become essential for discovering drugs and for designing enzymes that do major industrial work (see page 44). Attempts to visualize these arrangements of atoms have been vastly improved by computational chemistry, something that chemists now use to probe hidden relationships within materials but that 50 years ago was the province of an elite few. Today that power is in the hands of many: Intricate calculations have been built into computer programs, and computers to handle these programs have been built into analytical instruments (see page 51).

When it comes to transformations, it is harder to think of one bigger than that brought about by the advent of plastics. Many of them, invented during the middle of the 20th century, have made the objects in our lives lighter, more durable, and much easier to produce. Durability’s downside, however, is a persistent trash problem for society (see page 56).

Another major change has been wrought by industrial catalysis and the ability to “crack” crude oil into a variety of usable components. Originally used to derive fuels—including high-octane aviation fuel that helped Allied planes outfly Axis fighters in World War II—catalysis has grown to help produce 90% of the industrial chemicals we now use (see page 64).

In the quest to understand compounds and control their behavior, chemists have had invaluable assistants: analytical instruments. The pH meter, nuclear magnetic resonance spectrometer, and automated DNA sequencer, among many others, have helped chemists do things better and faster and pose questions no one thought of before these tools came into use (see page 70).

During the past several decades, chemists have been posing new questions about the effects of their products. Environmental awareness has not always been a hallmark of the field, and although chemists now think about the life cycles of products and inadvertent effects more than they used to, many in the enterprise believe that practitioners still have a way to go (see page 75).

C&EN has reported on many highlights of these nine trends during our 90 years, and they are noted in “From C&EN Archives” boxes in each story. You can freely access the articles mentioned in each box through the online versions of the nine stories, at http://cen.acs.org/ninety.html.

As an added bonus, there is a special poster, illustrating these major developments and more, in the middle of this issue. We offer it, and our 90-year chronicle, in the same spirit our predecessors did at the very beginning: for your approval.

MORE ON THIS STORY

Introduction: Nine For Ninety | PDF

Chemical Connections | PDF

Antibacterial Boom And Bust | PDF

Small Science, Big Future | PDF

Understanding The Workings Of Life | PDF

Chemistry By The Numbers | PDF

Plastic Planet | PDF

The Catalysis Chronicles | PDF

Giving Chemists A Helping Hand | PDF

It's Not Easy Being Green | PDF

Readers' Favorite Stories | PDF

Nine Decades Of The Central Science | PDF

How Chemistry Changed the World | C&EN's 90th Anniversary Poster Timeline

Trying To Explain A Bond

A Toast To C&EN At 90

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter