Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Biological Chemistry

Gut Bacteria Free Hidden Mycotoxins From Food

Health: Current detection methods don’t look for toxin derivatives

by Louisa Dalton

February 7, 2013

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 91, Issue 6

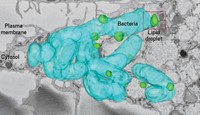

Food inspectors around the world screen foods made from crops such as peanuts or wheat, looking for fungal toxins that can cause ailments from diarrhea to cancer. New research suggests that when people eat those foods, bacteria in their guts may unleash the toxins from compounds that the safety screens don’t look for (Chem. Res. Toxicol., DOI: 10.1021/tx300438c).

Government agencies may need to regulate these toxin derivatives as they already do the unmodified mycotoxins, the researchers say.

Mycotoxins can enter the food supply after fungi deposit the compounds on food crops. Across the globe, government agencies, including FDA, set limits for the amount of certain mycotoxins permitted in human food and animal feed.

But in the past decade, scientists have discovered that plants modify the toxins to protect themselves, often by tacking on a sugar or sulfate group; the change renders the toxins less harmful to the plants. Current tests run by food inspectors do not look for these “masked” mycotoxin derivatives.

Chiara Dall’Asta, a chemist at the University of Parma, in Italy, and her colleagues wanted to find out what happens to these derivatives during digestion. They incubated three common ones in conditions found along the human digestive tract, from mouth to large intestine. One compound was the toxin deoxynivalenol masked with a glucose molecule, and the other two were derivatives of zearalenone.

Fecal bacteria freed the toxins from their masking groups under conditions similar to those found in the large intestine. It took the microbes 24 hours to completely cleave the derivatized deoxynivalenol, but only 30 minutes to release zearalenone.

A team in Scotland, led by Silvia Gratz of the University of Aberdeen, reported similar findings last month (Appl. Environ. Microbiol., DOI: 10.1128/aem.02987-12).

These studies are the first reports showing that, under conditions similar to those in the body, human gut bacteria can return the plant-masked mycotoxins to their original and potentially harmful state, says Franz Berthiller, at the University of Natural Resources & Life Sciences, in Vienna. To better understand the compounds’ toxicology, he thinks researchers must determine how much of the freed toxin reaches the bloodstream from the large intestine.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter