Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Biological Chemistry

Newscripts

Fear Of Stink, Driven By Pheromones

by Sarah Everts

February 25, 2013

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 91, Issue 8

Lurking among us are foolish folks who fork out cash for deodorants even though their armpits don’t smell. This is the take-home message of a recent article in the Journal of Investigative Dermatology (DOI: 10.1038/jid.2012.480).

It’s a fun study, but the results aren’t that surprising. Researchers have known for years that some people in Europe (2% of the population) and most people of Asian descent are fortunate enough to have two copies of a recessive gene that makes their armpits relative stink-free zones.

That’s because the gene codes for a protein involved in transporting molecules out of special sweat glands that appear in armpits at puberty. These malodor-producing glands are called apocrine glands, and they differ from eccrine glands, which are found all over the body and produce the salty fluid commonly associated with sweat and body temperature regulation.

Apocrine glands typically excrete all manner of waxy molecules that armpit bacteria love to feast on. It’s the leftover, metabolized molecules, such as trans-3-methyl-2-hexenoic acid, which give many human bodies that oh-so-ripe odor. Because the difference between stinky and stink-free is a gene involved in transporting armpit molecules, common wisdom in the field is that people without body odor have a dysfunctional transporter. What’s really new in the article is simply the observation that among the 2% of folks in the U.K. who probably don’t need to apply deodorant, 78% still do.

Okay, so why is this not really surprising? For one, the U.K. is dominated by people who have smelly armpits. If they don’t, it’s because they have two copies of the recessive, odorless allele of the gene, which behaves in a rather Mendelian fashion, says Ian Day, the University of Bristol researcher who led the study.

Being stink-free is rare in the U.K., so both parents of an odorless child are probably heterozygous. That means they carry one dominant allele of the gene and one recessive allele, but they themselves are stinky. Statistically, only one-quarter of these parents’ kids will be stink-free.

So you can imagine that odoriferous parents are likely to give their awkward teenagers deodorants in anticipation of that day when their bodies start announcing adulthood. And they probably do it prematurely, so that their teenagers don’t suffer ridicule from other, better-prepared schoolmates.

The second reason the study findings aren’t earth-shattering is that advertisers have spent the better part of the past century putting the fear of stink into humanity. They had to, because back in the 1910s, nobody was buying the newly invented deodorants or antiperspirants, in part because people didn’t think they needed the products. Turns out advertising successfully put the fear of stink in many folks because the deodorant and antiperspirant industry is now worth $18 billion annually. Many deodorant users among the stinkless 2% have probably just drunk the Kool-Aid or are hedging their bets.

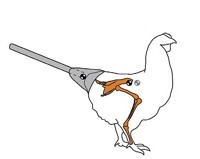

The humble male silk moth turns into a sex-crazed female-seeking missile after a single whiff of her sex pheromone. Although silk moth pheromones were discovered in the 1950s, it’s taken until now for scientists to harness this force of nature to drive a robot.

A report in the journal Bioinspiration & Biomimetics (DOI: 10.1088/1748-3182/8/1/016008) details how a male moth was attached to a free-moving polystyrene ball so that the insect could guide a robot toward the pheromone in the same way a computer mouse’s trackball drives a cursor. The team says that this could be a blueprint for biomimetic robots, leaving Newscripts uneasy about a future with lusty insect cyborgs.

Sarah Everts wrote this week’s column. Please send comments and suggestions to newscripts@acs.org.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter