Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Pharmaceuticals

Accelerating Diabetic Wound Healing

Drug Development: Inhibiting an enzyme involved in tissue remodeling helped stubborn wounds heal in diabetic mice

by Erika Gebel Berg

October 3, 2013

Each year, tens of thousands of people with diabetes in the U.S. have a lower limb amputated because a small foot wound failed to heal. With diabetes rates on the rise, scientists are eagerly searching for effective treatments for the ulcers that develop from these unhealed wounds. Now, researchers have identified an enzyme that’s rampant in diabetic wounds and may interfere with healing (ACS Chem. Bio. 2013, DOI: 10.1021/cb4005468). Inhibiting the enzyme accelerated wound healing in diabetic mice, suggesting a path to new drugs.

When tissue gets damaged, a cascade of physiological events occurs to promote healing, including inflammation, the formation of new blood vessels, and scarring, says Mayland Chang of the University of Notre Dame. “In diabetics, the process gets stalled.” As a consequence of diabetes, these patients often develop damage to blood vessels, which starves tissues of oxygen and alters the normal healing process.

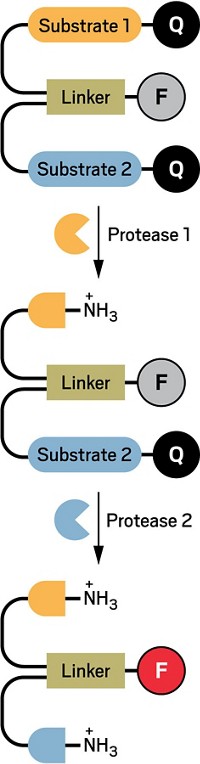

Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are a family of 26 enzymes that are involved in remodeling the extracellular matrix of tissue as part of the wound healing process. Scientists know little about the roles of individual MMPs and how they behave in people with diabetes. One obstacle to understanding MMP function is that most current analytical methods “do not distinguish between inactive and active MMPs,” Chang says. So even if a researcher finds a certain MMP in a wound, she can’t say whether or not the enzyme is doing anything.

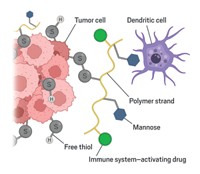

To help identify MMPs that turn on during wound repair, Chang and colleagues developed a method that fishes out only the active MMPs from wound tissue samples. To grab the proteins, they used micrometer-sized polymer beads covered in a small molecule that binds to the active sites of most MMPs. The active sites of inactive MMPs are inaccessible, Chang says, so the beads snag only active enzymes. After washing away any unbound molecules, the researchers can analyze their haul with mass spectrometry.

As a first test of the method, the researchers studied small open wounds they made on the backs of healthy and diabetic mice. As expected, wounds on the diabetic mice healed more slowly than those on healthy animals. During the healing process, the researchers took tissue samples from the wounds and mixed them with the small-molecule-decorated beads. The team pulled out active MMP-8 and MMP-9 in both normal and diabetic wounds. Seven days after the wounds were made, levels of MMP-9 were almost two times as high in diabetic wounds as in normal wounds, suggesting that MMP-9 is a roadblock to swift healing.

The researchers next treated wounds in diabetic mice with inhibitors for either MMP-8 or MMP-9. The wounds treated with the MMP-9 inhibitor were 92% healed after 14 days, but those treated with a placebo compound lagged, with only 74% wound closure. The MMP-8 inhibitor actually slowed wound healing: Animals receiving that molecule had only 58% wound closure on day 14 compared to 73% in those getting a placebo. The results suggest that if scientists can understand the roles of the enzymes involved in diabetic wound healing, Chang says, they can target their treatment method to inhibit only the troublesome MMPs and leave the helpful ones alone.

Picking out only the active MMPs is a “clever approach,” providing important information that can’t be accessed with other methods, says Richard D. DiMarchi of Indiana University, Bloomington. He thinks the method also could help identify active MMPs involved in other diabetic complications, such as eye, kidney, and nerve disease. DiMarchi and Chang agree that the next step though, is to study MMPs found in human diabetic ulcers.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter