Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Environment

Funeral Pyres Release Atmosphere-Warming Aerosols

Climate Change: Outdoor cremation rituals in South Asia are a previously unaccounted for source of carbon aerosols

by Deirdre Lockwood

October 11, 2013

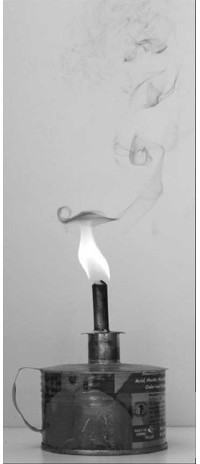

As part of a Hindu funeral ritual, family members burn the body of their deceased over an open wood fire for hours. Such pyres are burned in about 7 million funerals each year in India and Nepal, consuming about 50 to 60 million trees. As a result, funeral pyres in South Asia are a significant regional source of carbon aerosols that can warm the atmosphere, according to a new study (Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2013, DOI: 10.1021/ez4000669).

Burning wood, fossil fuels, and other kinds of organic matter releases tiny, carbon-rich particles that absorb solar radiation and help retain heat in the atmosphere. These carbon aerosols are the second largest human-made contributor to global warming after carbon dioxide. And when the particles fall onto snow and ice, their dark color causes the ice to absorb more sunlight, speeding up melting of glaciers.

Studies that tally the human-made sources of carbon aerosols have accounted for the regional burning of fossil fuels, forests, and biofuels such as wood, crop residue, and animal dung. But these inventories may underestimate actual emissions by as much as a factor of three, according to a study published earlier this year (J. Geophys. Res. Atm. 2013, DOI: 10.1002/jgrd.50171).

Rajan K. Chakrabarty of the Desert Research Institute, a Nevada state environmental research center, thought that funeral pyre burning in South Asia might be an important source of carbon aerosols that is missing from regional and global inventories. So he and his colleagues used filters to collect particulates from the smoke of seven funeral pyres in India. Then they analyzed the compounds in the particles using thermal and optical carbon analysis and measured the light absorption of the deposits with multiwavelength transmission spectroscopy.

The findings surprised them, Chakrabarty says, because they expected to find mainly black carbon, which is a major component of soot. Instead, the filters were a rich brown-yellow color, evidence of another class of sunlight-absorbing particles, organic carbon aerosols known as brown carbon. Chakrabarty attributes this unique aerosol composition to the inefficient burning of the pyres and the mixture of fuel prescribed for the ritual by Hindu scripture, which includes mango and sal trees.

The group found that funeral pyres release up to 53 times more organic carbon aerosols per unit of mass burned than do biofuels used for household cooking and heating. Based on the total biomass burned per year in South Asian funeral pyres, they estimate that the practice emits about 94 billion g of carbon aerosols per year, which is about 23% of the amount produced by fossil fuel burning in the region, and 10% of that produced by biofuel burning.

Mark Z. Jacobson, an atmospheric scientist at Stanford University, says that although funeral pyres make a small contribution to carbon aerosol pollution on a global scale, the study provides the most thorough analysis yet of their emissions. It also highlights the regional impact of brown carbon, which is not included as a heating component in most climate models, he says.

Next Chakrabarty and his colleagues plan to characterize the physical properties of individual aerosol particles from the pyres—such as how much radiation they can absorb—to estimate the particles’ contribution to regional atmospheric warming.

The use of electric cremation systems or pyres that consume less wood could mitigate the release of carbon aerosols and lessen the custom’s warming and pollution impacts, Chakrabarty says. But the cultural importance of the practice makes such changes difficult.

Observant Hindus he has spoken with “want to make sure their corpses are burned in accordance with scripture,” Chakrabarty says. To understand the challenge, he says, “extrapolate this to the sentiment of 200 million people.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter