Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Education

Newscripts

Chemically Inspired Music, Tuneful Apathy

by Sarah Everts

March 24, 2014

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 92, Issue 12

You may think that the trend of communicating cutting-edge science with music is innovative. After all, there’s been a flux of science rap songs about topics as diverse as acid-base chemistry, irrational numbers, and even the skeletal system. And then last year saw the launch of a rap competition for students called Science Genius B.A.T.T.L.E.S. in New York City.

Yet humans rarely prove themselves truly original: We’ve been composing science-y songs for ages. Consider the 18th-century ballads about longitude, the precise measurement of which long stymied explorers. Or the 1904 Broadway musical “Piff! Paff! Pouf!” featuring a tune about the then-hot new element radium. There’s an opera about Auguste Piccard, the Swiss who voyaged to the stratosphere in 1931 via a hydrogen balloon and a pressurized aluminum capsule. And let’s not forget the odes to pi, by musicians such as eclectic singer-songwriter Kate Bush and classically bent mathematicians who’ve transposed the nonrepeating number onto musical notes for the pi-ano.

But leave it to the alchemists of yore to take the idea of communicating science through music to a whole ’nother level. Or specifically, leave it to the German alchemist Michael Maier.

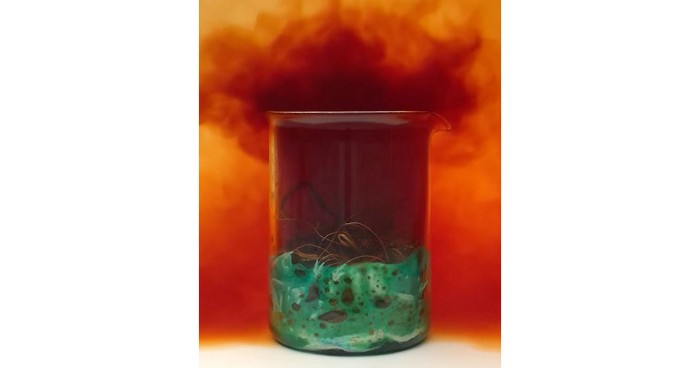

In 1617, Maier created the “Atalanta Fugiens,” a guide for producing the philosophers’ stone that features a musical score and many gorgeously bizarre engravings. The philosophers’ stone is the long-sought-after agent of transmutation, capable of turning base metals into precious gold and silver, and an elixir for human health and longevity.

As is the case for many alchemical recipes, the images in “Atalanta Fugiens” provide intentionally obtuse, secretive instructions for sublimation, calcination, and other alchemical processes. But before you assume that the musical score was simply a recommended laboratory soundtrack for the trendy 17th-century alchemist, look to the research of Chemical Heritage Foundation scholar Donna Bilak. She’s discovered that the “Atalanta Fugiens” score acts as a musical recipe for the philosophers’ stone, where the three individual parts of the music represent ingredients in the refining process, namely mercury, sulfur, and salt. It’s as if a modern-day chemist decided to pen a symphony and add it to the Materials & Methods section of a research paper, where different instruments correlate to various chemical starting materials. (Please, tell us if someone has done this.)

Bilak says she’s heard a few renditions of the “Atalanta Fugiens” music, and she is arranging for another professional recording this month. “You can’t snap your fingers and sing along to the music,” Bilak says. “But it’s eerily beautiful.”

But not everyone has a penchant for translating science into music, or even listening to it. In fact, about 1–3% of people just don’t enjoy a catchy tune—ever. This discovery is reported in a recent paper in Current Biology, from a team of researchers who wanted to test the cultural assumption that “the ability of music to induce pleasure is universal” (2014, DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.01.068).

Turns out, it’s not. Folks who don’t appreciate the genius inherent in a well-curated music mix now have a diagnosis: musical anhedonia. They can still derive hedonist delight from other pleasures, such as sex and food, and they aren’t tone-deaf. They even understand the emotional significance of a nostalgic tune. The musically indifferent just don’t join the majority of humanity who ranks music “among the highest sources of pleasure,” the researchers say. Nor are these folks likely to pen an opera about their scientific escapades anytime soon.

Sarah Everts wrote this week’s column. Please send comments and suggestions to newscripts@acs.org.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter