Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Business

Biotechs Beat Pharma In First-Half Earnings

Big biotech firms outshone traditional drugmakers in the first half of 2014

by Lisa M. Jarvis

August 11, 2014

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 92, Issue 32

Boosted by successful new products, large biotech firms outperformed their big pharma counterparts in the first half of 2014. Major drug firms, experiencing a continued drop in sales and earnings, resorted to quick fixes to try to solve their growth problems.

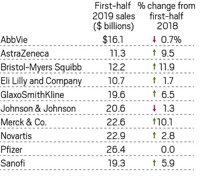

Of the 11 major drug firms tracked by C&EN, only four saw an increase in sales during the first half of the year. And none managed to achieve the double-digit sales growth that a decade ago was the norm for big pharma.

Eli Lilly & Co. was the sorriest of the bunch. Half-year earnings were down 40.7% to $1.5 billion, based on a 16.6% drop in sales. The slide was in large part due to generic competition for the antidepressant Cymbalta, which lost patent protection in December. Cymbalta sales fell from $2.8 billion in the first half of 2013 to $880 million in the first half of this year.

Lilly’s results still exceeded stock analysts’ expectations thanks to healthy growth in its diabetes franchise. But if the company sticks with its current portfolio and pipeline, analysts expect it will need another five years to get back to the sales level it enjoyed during Cymbalta’s patent life.

Despite a challenging few years, Lilly continues to shun the strategy many of its competitors are taking: trying to buy their way out of a slump. Indeed, the first six months of the year brought a stream of deals, or attempted deals, designed to reinvigorate businesses.

Some were focused as much on tax savings as they were on bolstering product portfolios or new-drug pipelines. In the first half of the year, Pfizer attempted a takeover of AstraZeneca, which rejected the $119 billion offer as too low. If Pfizer had been successful, the company planned to move its headquarters to the U.K., a shift that analysts say would have lowered its taxes on existing products by 5% and granted it a more favorable tax rate for new drugs.

Under U.K. takeover law, Pfizer will have to wait six months from its last overture, made in May, if it opts to again pursue AstraZeneca.

AbbVie had more success in lowering its tax base through an acquisition. The North Chicago-based firm won over Shire, an Irish drug company that focuses on rare diseases, neuroscience, and gastrointestinal disorders. After several rounds of discussions, Shire’s board accepted AbbVie’s offer of $54 billion in cash and stock. By moving its headquarters to the U.K., while still keeping the majority of its operations in the U.S., AbbVie is expected to lower its tax rate from 22% to about 13%.

Other firms made smaller, arguably more strategic, purchases and divestitures in the first half. In a series of swaps announced in April, Novartis paid $16 billion for GlaxoSmithKline’s oncology products unit and GSK took on Novartis’s vaccines business. The two companies also created a joint venture to house their consumer products businesses. At the same time, Novartis sold its animal health business to Lilly for $5.4 billion.

Merck & Co. also took part in the asset swapping. In May, the New Jersey-based drugmaker sold its consumer products unit to Bayer for $14.2 billion while at the same time entering a pact with Bayer worth up to $1 billion to codevelop a series of cardiovascular drugs.

A few weeks later, Merck paid $3.85 billion for Idenix Pharmaceuticals, a Cambridge, Mass.-based biotech firm that brought a key hepatitis C virus (HCV) drug candidate to Merck’s portfolio. Merck is hoping to replicate the success enjoyed by Gilead Sciences, which has seen sales catapult over its biotech peers and even surpass those of several big pharma firms since last year’s launch of its HCV drug Sovaldi.

Skyrocketing Sovaldi sales meant Gilead’s first-half earnings nearly tripled to $6.4 billion. Sales were $11.5 billion, up 118% over the first half of 2013.

Sovaldi has been on the market only since December but already accounts for about half of Gilead’s sales. The $5.8 billion the pill brought in during the first six months of the year puts it on track to be the most successful drug launch in history.

That trajectory also has made Sovaldi the poster child for drug price reform. Although it is currently the most effective treatment for HCV, offering a cure for many patients, Sovaldi also costs about $84,000 for a full course of treatment.

Last month, a congressional probe into its pricing intensified. Two senators asked the biotech firm to provide a slew of documents related to the pill. They are particularly interested in Gilead’s purchase of Pharmasset, which discovered the molecule, and how much the two companies spent to discover and develop it. The worry is that Sovaldi could cost Medicare as much as $2 billion between 2014 and 2015.

That inquiry followed an earlier request by three members of the House of Representatives Committee on Energy & Commerce for Gilead to explain how it arrived at the price of Sovaldi.

Gilead is so far standing firm on pricing, and the company’s fortunes will only improve with the expected approval in October of a drug that combines Sovaldi with ledipasvir, another antiviral in its pipeline. The biotech will also benefit from the recent Food & Drug Administration approval of Zydelig for three kinds of blood cancer. Although a competing drug from Johnson & Johnson, Imbruvica, appears to work better, analysts still think Zydelig sales will exceed $1 billion annually by 2017.

Gilead’s stronghold in the HCV market is Vertex Pharmaceuticals’ loss. Last year, Vertex conceded defeat for its HCV drug Incivek, which when launched in 2011 represented a major advance in treating the infection. Sales of the drug exceeded $1 billion in 2012, but by 2013 HCV patients were holding off treatment as they waited for the launch of drugs from Gilead and other companies. U.S. sales of Incivek totaled just $13 million in the first half of 2014.

Now reliant mainly on its cystic fibrosis treatment Kalydeco, Vertex saw sales for the first six months of the year get cut in half to $257 million, and the company posted a loss of $293 million.

But Vertex could soon enjoy a turnaround. Later this year the company will ask U.S. and European regulators to approve a treatment that combines Kalydeco with another drug to address a larger portion of the cystic fibrosis population than Kalydeco can on its own. Analysts expect the new therapy’s sales to peak at more than $3 billion per year.

More typical of the biotech sector was Biogen Idec, which grew earnings by 39.1% in the first half to $1.4 billion on a 45.0% increase in sales. The firm’s strongest performer was the multiple sclerosis treatment Tecfidera, which saw sales increase more than six times over to $1.2 billion. Buoyed by that drug and others, Biogen did what its big pharma brethren can only dream of doing: It raised its expectations about sales and earnings for the full year.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter