Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Biological Chemistry

To Outwit Plant Defenses, Hungry Caterpillars Turn Chemists

Insects modify a single attachment point to deactivate a toxin in maize

by Carmen Drahl

October 3, 2014

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 92, Issue 40

Score one for the fall armyworm in the game of survival: Researchers report that the plant-eating caterpillar and its close relatives use a strategy worthy of an organic chemist to defuse a poison found in maize leaves. The finding could be of use in pest control.

Maize and related crops such as wheat and rye contain defense compounds called benzoxazinoids. Plant cells store the highly reactive molecules masked with the sugar β-

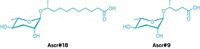

Daniel G. Vassão set out to learn why. The biochemist at Germany’s Max Planck Institute for Chemical Ecology convinced an international team to help him analyze caterpillar guts and feces with liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry and nuclear magnetic resonance. The team found that the insects’ guts contain an enzyme that reattaches the sugar to a particular benzoxazinoid. However, the enzyme does so with the opposite stereochemical configuration compared with the original plant molecule (Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, DOI: 10.1002/anie.201406643). The plant can no longer unmask the modified toxin.

“These insects can one-up the plant defensive machinery,” Vassão says. Only a few similar defense strategies are known so far in the insect world. “I think many other examples of the manipulation of stereochemical centers during insect metabolism are waiting to be described,” Vassão adds.

Jocelyn G. Millar, an insect chemical ecologist at the University of California, Riverside, enjoyed reading about how the researchers used LC/MS to watch the active form of the plant toxin be continuously depleted as it travels through the armyworm’s gut. “You have to love the ingenuity of nature!” he says.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter