Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Education

Newscripts

Redefining A Planet, Rat Massage Is Golden

by Stephen K. Ritter

October 13, 2014

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 92, Issue 41

Once upon a time, a planet was one of the nine balls of rock or gas that orbited our sun. But then some astronomers started finding planetoids orbiting the sun between Mars and Jupiter and out beyond Neptune. And then they started finding what look like planets orbiting other suns throughout the galaxy.

These observations created a problem for the International Astronomical Union (IAU), which is in charge of naming things in space. Some scientists started splitting hairs over what can be called a planet, going so far as to question whether Pluto still qualified. IAU thus tried to tackle the question at its 2006 annual meeting.

Alas, the astronomers couldn’t come up with a definition that everyone could agree on. In the end, they voted and were left with this: A planet is a celestial body that is in orbit around the sun, is round or nearly round, and has cleared the neighborhood around its orbit.

But this definition remains unsatisfying. For one thing, it only applies to planets in our solar system. And it booted Pluto from the planet club, because it doesn’t meet the last requirement. Pluto is now called a dwarf planet—an object the size of a planet but that is “neither a planet nor a moon or other natural satellite.” So dwarf planets aren’t real planets (even if a miniature schnauzer is still a dog).

However, the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics has come to Pluto’s rescue. On Sept. 18, the center hosted a public debate among planetary science experts as to what a planet is or isn’t. One scientist argued that “planet” is a culturally defined word that changes over time and that Pluto is a planet. Another defended the IAU definition. Others tendered different options. Then the audience got to vote.

The winning definition is that a planet is “the smallest spherical lump of matter that formed around stars or stellar remnants.” Although that is perfectly vague, it unofficially brings Pluto back into the planetary family fold. IAU is being coy about considering a re-redefinition.

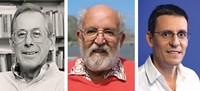

What can you learn from massaging baby rats? Answer: how to improve the health outcome for premature human babies. Research on the topic by Duke University neuroscientist Saul Schanberg and his team just received a Golden Goose Award.

These awards are given by a consortium of scientific societies and nonprofit institutes to honor scientists whose taxpayer-funded research may not have seemed significant at the time it was carried out but resulted in a significant societal benefit. The award is a countermeasure to the Golden Fleece Award, given to call out wasteful federal spending.

In 1979, Schanberg and his group were studying an enzyme and a growth hormone that are biomarkers for fetal and newborn development. They had to separate rat babies from their moms and in doing so found that, although the babies were kept fed and warm, they did not thrive and the biomarker levels dropped.

To make a long story short, they noticed that rat moms spend a great deal of time grooming and licking their newborns. Wondering if the tactile attention was important, they started using a small brush to stroke the separated babies. That was the missing link—the enzyme and hormone levels rose and the kids turned out okay.

In the 1980s, neonatal specialists read about Schanberg’s work and started trying it with premature infants, with good effect. Today, massaging premature infants is becoming common practice.

Steve Ritter wrote this week’s column. Please send comments and suggestions to newscripts@acs.org.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter