Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Safety

Rail Safety Plan Under Fire

Effort to beef up tank cars is intended to prevent spills of flammable liquids

by Glenn Hess

December 8, 2014

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 92, Issue 49

After a string of fiery derailments in recent years, the federal government is moving to tighten regulations on mile-long trains hauling dozens of black, tube-shaped tank cars filled with crude oil or ethanol.

But chemical industry groups say that a set of rules proposed in July by the Department of Transportation (DOT) would also impose restrictions on flammable liquids, such as acetone, cyclohexane, and propylene oxide, that are rarely shipped in more than a few tank cars per train.

“Based on DOT’s own analysis, it is clear that the proposal was intended to specifically address very large train shipments of crude oil and ethanol,” says Thomas E. Schick, senior director of distribution, regulatory, and technical affairs at the American Chemistry Council (ACC), a trade association that represents the nation’s largest chemical companies.

But the proposed rule is written so broadly, Schick says, that its impact would reach far beyond just those two commodities. “The requirements should only apply to crude oil and ethanol shipments,” he asserts.

ACC and other stakeholders recently filed comments on DOT’s sweeping proposal, which was prompted largely by safety concerns arising from the surge in crude oil moving on the nation’s railways (C&EN, Aug. 18, page 22). DOT is currently reviewing the more than 2,000 comments it has received. The department expects to finalize the rules early next year.

Rail shipments of petroleum have skyrocketed from only 5,000 carloads in 2006 to 434,000 carloads in 2013. Booming oil production from shale-rich areas such as the Bakken formation in North Dakota combined with insufficient pipeline capacity means that crude oil is increasingly being shipped to coastal refineries in massive “unit trains” that are up to 105 cars long.

Ten derailments in the U.S. and Canada since 2008 resulted in crude oil spilling from ruptured tank cars, in some cases igniting in huge fireballs, according to the National Transportation Safety Board. The worst accident was a 72-car oil train that exploded in Lac-Mégantic, Quebec, in July 2013, killing 47 people.

Ethanol shipments have raised a similar concern. From 2006 to 2012, seven train derailments resulted in ruptured biofuel tank cars. Several crashes caused spectacular fires, including one near Cherry Valley, Ill., in June 2009. In that incident, one woman died and two other people were seriously injured while they waited at a nearby train crossing.

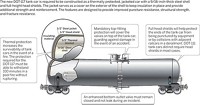

DOT says the type of tank car typically used to transport crude oil and ethanol—the DOT-111—isn’t built with thick enough walls to prevent punctures when it is involved in an accident (C&EN, March 31, page 19). Consequently, the proposed rules would give different types of shippers two to five years to phase out or upgrade their fleets.

Under the proposal, shippers could retrofit their DOT-111s, whose design dates back to the 1960s, by adding extra protection such as an outer steel jacket, thick steel plates at the ends, and thermal insulation. Or they could replace them with new tankers built to the latest safety specifications.

The proposed requirements would apply to “high-hazard trains” carrying 20 or more tank cars of flammable liquids. DOT states that “only crude oil and ethanol shipments would be affected by the limitations of this rule as they are the only known Class 3 (flammable liquid) materials transported in trains consisting of 20 cars or more.”

But chemical industry officials say a wide array of other flammable liquids, including many commercial chemicals hauled by rail, would also be impacted. The proposal defines all trains with 20 or more cars of flammable liquids as high hazard without consideration of a key operational distinction—whether the cars are hauled in what are called manifest or unit trains, notes Jennifer C. Gibson, vice president of regulatory affairs at the National Association of Chemical Distributors (NACD), a trade group.

In the freight rail industry, a unit train consists of 75 or more essentially identical cars loaded with the same bulk commodity that are all tendered to the railroad in a single block by one shipper. A manifest train, however, hauls a mixture of railcars—such as boxcars and tank cars—loaded with different types of cargo.

“Most trains carry well over 20 railcars,” Gibson says. “The proposed rule would subject all of the cars to the same restrictions,” not just shipments of crude oil and ethanol.

For its part, ACC argues that the final rules should apply only to the unique transportation risks posed by unit trains hauling large volumes of crude oil and ethanol. The chemical manufacturers’ association stresses that flammable liquid chemicals are not shipped in unit trains.

“ACC members tender their flammable liquids to railroads in much smaller volumes for movement in manifest trains together with cars containing various other types of freight, not necessarily even hazardous materials,” the group says in its comments. “We urge DOT to revise the proposed rules to place the greatest priority on shipments of flammable liquids moved in high-volume train configurations.”

DOT says unit trains have a higher risk of accidents because they are longer, heavier, and more challenging to control, slow down, and stop than manifest trains.

Environmental groups support tougher rules on all rail shipments of flammable liquids and are urging DOT to press ahead. But they want regulators to immediately ban the use of DOT-111 tank cars for oil service.

“Allowing these dangerously deficient tank cars to remain in service is playing Russian roulette with public safety,” says Jared Margolis, an attorney at the Center for Biological Diversity, an advocacy group. “These tank cars put our health and the environment at risk, so allowing their continued use is unacceptable.”

But chemical makers and other shippers say even the proposed five-year phaseout schedule for retiring or updating their fleets is unrealistic. “The number of facilities in existence that are capable of building new railcars and retrofitting other tank cars is limited,” NACD’s Gibson points out.

At least 67,000 tank cars that currently transport crude oil, ethanol, and other flammable liquids would need to be upgraded. Meanwhile, there is already a backlog of orders for about 53,000 new tank cars, according to the Railway Supply Institute, an industry organization.

The American Fuel & Petrochemical Manufacturers (AFPM), which represents the majority of refiners that transport crude oil by rail, estimates it would take at least 10 years to purchase new cars or retrofit old ones.

“Insisting upon a more aggressive schedule would risk tank car shortages, a significant loss in crude and ethanol rail capacity, and higher prices for consumers of petroleum products,” says David N. Friedman, AFPM’s vice president of regulatory affairs.

Friedman also faults DOT for ignoring the “root causes” of recent oil train derailments, such as track defects and infrequent rail inspections. “Nothing in this rule-making would require railroads to buy one more piece of track inspection equipment, hire one more qualified inspector, or inspect one more mile of track,” he says. The regulatory focus should be on preventing derailments, Friedman adds, because “the obvious answer is that the trains must remain on the tracks.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter