Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Antibiotics

Peptide-Drug Conjugate Kills Persistent Bacterial Cells

Antibiotics: Adding a peptide that penetrates cell membranes to an existing antibiotic allows the drug to enter bacterial sleeper cells that can cause chronic infections

by Sarah Webb

August 20, 2014

Pathogenic bacteria rely on a number of tricks to evade antibiotics. Some cells, for example, ramp down their metabolic activity and block the drugs from slipping through their membranes. Now researchers have linked a peptide to an established antibiotic so that the drug can enter these persistent bacterial cells, making the conjugate up to a million times more potent than the antibiotic alone(ACS Nano 2014, DOI: 10.1021/nn502201a).

“Currently, there are only a handful of leads for the development of therapeutics to eliminate” persistent bacterial cells, says Mark P. Brynildsen of Princeton University, who was not involved in the study. “This methodology could be a game changer.”

Persistent bacterial cells can cause chronic infections because they become dormant in the presence of antibiotics. In this dormant state, these so-called persister cells have less permeable membranes, which makes them impervious to many drugs that need to enter the cell to hit intracellular targets such as the ribosome. When antibiotic concentrations eventually drop, these sleeper cells can become active again, seeding the recurrence of the infection and providing opportunities for the development of antibiotic resistance. A large number of antibiotics are borderline obsolete because they are ineffective against persister cells, says bioengineer Gerard C. L. Wong of the University of California, Los Angeles.

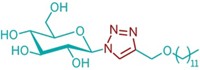

Developing new antibiotics is both time consuming and costly. So Wong and his UCLA colleagues, including Andrea M. Kasko, wanted to improve an existing drug that had little activity against persister strains. They picked the aminoglycoside antibiotic tobramycin, which blocks protein translation by the ribosome. The team wondered if they could improve its potency by adding a cell-penetrating peptide that disrupts the bacterial membrane and helps the drug enter persister cells.

Using a well-known cell-penetrating peptide as a template, the researchers designed and synthesized a 12-amino-acid peptide and then attached it to a primary hydroxyl group on tobramycin. They chose the location so that the peptide would not affect the antibiotic’s activity.

They first showed that this new molecule, Pentobra, could cross membranes and enter Escherichia coli. The team then compared the ability of Pentobra and tobramycin to kill persistent strains of E. coli and Staphylococcus aureus. Compared with tobramycin, the modified antibiotic was up to 10,000 times more potent toward E. coli persister cells, and up to a million times more potent against S. aureus ones. In addition, Pentobra was not toxic to mouse fibroblast cells, showing that the drug selectively kills bacterial cells and not mammalian cells.

“The results are very exciting, and the tobramycin-peptide conjugate may offer an alternative to conventional antibiotics to treat a variety of chronic infections,” says Kim A. Brogden of the University of Iowa.

Wong points out that because Pentobra and similar conjugates target bacteria in two ways, the molecules could thwart bacterial resistance mechanisms more effectively than other drugs.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter