Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Pollution

Fire Retardants Wash Out In Laundry

Water Pollution: The chemicals used in furniture and electronics may end up on clothing, wash off in laundry, and make their way to rivers and lakes

by Janet Pelley

October 1, 2014

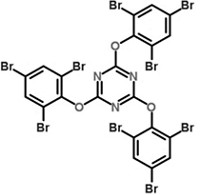

Flame retardants used in furniture and electronics work their way into aquatic food chains, accumulating in organisms from mussels to fish to seals. Scientists know that rivers and lakes receive significant amounts of fire suppressants from treated wastewater, but how the compounds get into sewage plants has remained a mystery. For the first time, a new study suggests that the biggest contributors are our washing machines. Flame retardants hitch a ride on our clothing and then come out in the wash, the researchers say (Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, DOI: 10.1021/es502227h).

Scientists worry about the fate of flame retardants because studies have linked the chemicals to cancer, neurotoxicity, and hormone disruption. Researchers have tried to chase the compounds as they go from consumer goods such as couch cushions and TV casings to accumulate in air, water, human breast milk, and aquatic food chains. “We know that flame retardants escape to house dust and that clothing gets dirty and accumulates dust,” says Erika D. Schreder, science director at the Washington Toxics Coalition, an environmental research and advocacy group in Seattle. Studies have also shown that sewage effluent is one of the largest sources of flame retardants to rivers and lakes, so “we thought that laundry water might be an important source of flame retardants,” Schreder says.

To test the hypothesis, Schreder and her colleague Mark J. La Guardia of the College of William & Mary’s Virginia Institute of Marine Science did some housework. They went to 20 households in Longview and Vancouver, Wash., near the mouth of the Columbia River, and convinced the residents to allow the scientists to vacuum and do laundry in their homes. The duo fit a conventional vacuum cleaner with a cellulose filter and sucked up dust from floors and carpets. The scientists washed a full load of laundry prepared by the residents and took a sample of the wastewater at the end of the agitation cycle. Schreder and La Guardia also visited the two sewage plants serving the households and grabbed samples of water entering and exiting the plant.

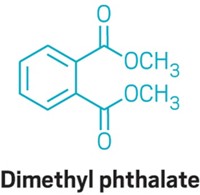

The scientists analyzed the dust and laundry wastewater samples with liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry and uncovered 21 flame retardants in the household dust, 18 of which also were in the laundry wastewater. The highest concentrations they measured came from chlorinated organophosphates, also known as Tris. These flame retardants, which have replaced banned or phased-out polybrominated diphenyl ethers, accounted for 72% of the retardants in the dust and 92% in the laundry wastewater.

Schreder and La Guardia then used the median concentration of each flame retardant in the washing machine water to estimate the expected level of flame retardants in water entering sewage plants if laundry wastewater were the sole source of the chemicals. “The estimates were very similar to what we measured coming into the treatment plants,” suggesting washing machines may be the dominant source of flame retardants for those plants, Schreder says.

Finally, the scientists estimated that every year the two treatment plants deliver 210 kg of Tris flame retardants to the Columbia River. If these discharges are typical of plants nationwide, that would mean that between 2 and 4% of the annual production of some Tris compounds gets washed down the drain via our laundry.

The researchers have filled an important knowledge gap on how flame retardants might move in the environment, says Amina Salamova, an environmental chemist at Indiana University, Bloomington. The data also hint that people may be exposed directly to flame retardants by the compounds riding on their clothing, she says.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter