Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Environment

Chronic Alcohol Use May Increase Levels Of Inflammatory Lipids In Adult Brains

Neurochemistry: Scientists try to understand how long-term alcohol use leads to neurological damage

by Puneet Kollipara

November 26, 2014

Excessive, long-term alcohol use can cause many neurological problems in people, including cognitive deficits and dementia. Still, scientists are only beginning to unravel the complex molecular mechanisms underlying these effects. Now a team of researchers reports that certain lipids in the brain that can cause inflammation may be linked to long-term alcohol exposure. Adult mice that consumed alcohol at will for nearly two months had significantly higher levels of these lipids in their brains than did animals not exposed to ethanol (ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2014, DOI: 10.1021/cn500174c).

Amina S. Woods of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, who led the team, says she was surprised to see virtually no studies on how alcohol affects lipids in the brain. Lipids, she says, compose more than half the brain’s weight. “To ignore the lipids is really not reasonable,” she says.

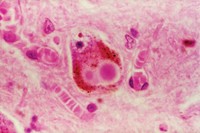

Woods and her colleagues chose to look at a family of signaling lipids called ceramides because they can cause inflammation and promote cell death in nerve cells. They also analyzed sphingomyelins, which are close cousins to ceramides. Sphingomyelins serve as an important component of nerve cell membranes and the fatty sheath that insulates them. Also when sphingomyelins are hydrolyzed, they produce ceramides.

To see how alcohol abuse might affect levels of these lipids, Woods and her colleagues observed 60 mice, some juvenile and some adult. They gave some of the animals free access to a 12% ethanol solution, which is roughly the alcohol concentration of wine. The other animals didn’t receive any alcohol. After 52 days, the researchers analyzed the lipid composition in the animals’ brains using electrospray mass spectrometry.

In adult mice that received the boozy drink, concentrations of all 18 ceramides were between 71 and 600% greater than in animals drinking just water. Meanwhile, concentrations of three of the 16 sphingomyelins studied were lower. However, the results were not the same in the brains of juveniles: Levels of six ceramides were actually smaller, by between 10 and 36%, compared with animals receiving just water, and the concentration of just one sphingomyelin were greater. Woods says her team doesn’t yet have an explanation for the differences in how adult and juvenile brains responded to the alcohol.

Despite the interesting results, the study has limitations, says Roberta Ward, a neuroscientist at Imperial College London who wasn’t involved in the work. The data clearly show molecular changes in the brain, but they don’t pinpoint the cell types experiencing those changes. Also, Ward says the study doesn’t detail how the molecular effects changed with time and different alcohol intakes, which could explain how quickly the brain chemistry shifts.

Fulton T. Crews, a neuroscientist at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine, agrees that understanding which cell types in the brain experience these changes would be helpful. To try to validate the lipid connection, he says that researchers could use brain imaging techniques to look for these lipid changes in people. Also he points out that changes in ceramides and sphingomyelin occur in the central nervous systems of people suffering from neurological diseases such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or Lou Gehrig’s disease.

Woods acknowledges that the study is merely a first step. She hopes other scientists will elucidate how chronic alcohol use affects these lipids and how these lipids in turn might produce cognitive and neurological problems.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter