Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Education

Newscripts

Back To The CoffeeHouse

by Rick Mullin

May 25, 2015

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 93, Issue 21

On a Sunday evening earlier this month, the basement performance space of the Cornelia Street Café in New York City resonated in candlelight to the gonging of glass and metal objects held over the heads of patrons by Katie Down, a music therapist. On stage, her colleague, Luana DeAngelis, percussed other gongs and spoke of healing powers of sound.

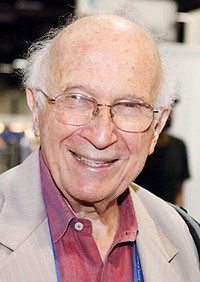

In the front row sat the evening’s host, Roald Hoffmann, a chemistry professor at Cornell University. As far from a chemistry lab as the café basement seemed to be, the recipient of the 1981 Nobel Prize in Chemistry was clearly in his element.

Hoffmann with the assistance of coorganizer David Sulzer, a Columbia University neurologist, has been hosting Entertaining Science, a monthly meeting of science and the arts, at the café for over a decade. He describes his science cabaret evenings as a haven for the humanities, a space where time is cast back to an age when poets and chemists swam in the same waters.

Little known fact: The word “psychosomatic” was coined by the poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge in describing his first experience inhaling nitrous oxide. Coleridge, in fact, was nuts about chemistry. When he told his good friend, the pioneering chemist Humphry Davy, that he wanted to attack chemistry like a shark, he wasn’t saying that he wanted to harm science. Coleridge meant that he wanted to devour it.

Percy Bysshe Shelley was another poet strongly drawn to science. He was constantly in trouble as a young boy for starting fires with experiments staged to scare his sisters. He also liked to electrocute them, electricity being all the rage when Shelley was a boy in the late-18th and early-19th centuries.

But poets’ predilections for science predated the Romantics. Charles Darwin’s grandfather, Erasmus Darwin, was a published poet as well as a physician and theorist on evolution. And his friend in the colonies, Benjamin Franklin, was a prolific writer and inventor with an interest in music. Franklin counted among his inventions the glass harmonica, a musical instrument that produces sound by means of friction against a graduated series of spinning bowls.

Going back, of course, we have Leonardo da Vinci, the archetypical artist and inventor.

Going forward, we have a problem.

A rift between science and the arts began tearing shortly after the younger Darwin’s trip around the world on the H.M.S. Beagle. By the mid-20th century, the two went their separate ways, with science solidifying its status as the rational arbiter of the truth.

Hoffmann is not alone, however, in keeping a candle lit for the Romantics. Just as the coffeehouses of England and its North American colonies were favorite meeting places of artistic science enthusiasts in Franklin’s time, cafés and cabarets such as Hoffmann’s have sought to reestablish a natural balance in cities like New York and Washington, D.C. For example, science writer Ivan Amato hosts the monthly DC Science Café at Busboys & Poets restaurant.

“I think there have always been people who have bridged the divide,” Hoffmann says. He cites his “poetry guru,” the late A. R. Ammons, who was an English professor at Cornell. “He was very well educated, especially in geology and biology, and used natural history and biological themes consistently in his work,” Hoffmann says.

It is the creative possibility of combining themes that makes Hoffmann’s cabaret nights well worth his effort. “For one day a month,” he says, “the world seems like it should be.”

Rick Mullin wrote this week’s column. Please send comments and suggestions to newscripts@acs.org.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter