Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Materials

New Contact Lens Coating For Fighting Eye Infections

Biomaterials: An easy dipping process coats disposable lenses with a robust, invisible antimicrobial polymer film

by Prachi Patel

June 29, 2015

Researchers have come up with an economical one-step process to coat contact lenses with an antimicrobial film (Biomacromolecules 2015, DOI: 10.1021/acs.biomac.5b00359). The coating could cut the risk of eye irritation and serious eye infections in the 140 million contact lens wearers worldwide.

Microorganisms such as bacteria and fungi that grow on the surface of contact lenses cause irritation in five out of 100 users every year, says Mark D. Willcox of the University of New South Wales, in Sydney, Australia, who was not involved in the new work. One in 2,500 wearers, meanwhile, develops an infection that is difficult to treat and can lead to vision loss. Despite the availability of new contact lens materials and better cleaning solutions, the risks of these conditions have remained the same for the past two decades, he says.

Researchers have in recent years tried various antimicrobial coatings for contact lenses and lens cases. Silver coatings have been commonly studied, but the materials can leak out of the lens, and their antimicrobial effect fades over time, says Yi Yan Yang of the Institute of Bioengineering & Nanotechnology, in Singapore, and coauthor of the new study. Coatings made of antimicrobial peptides such as melamine are promising, she says, but the peptides are expensive to make and difficult to coat on a lens surface.

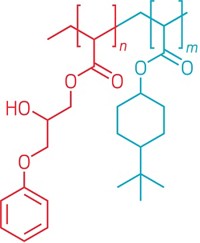

Yang, James L. Hedrick of the IBM Almaden Research Center, in San Jose, Calif., and their colleagues made a robust, invisible antimicrobial coating by simply dipping a cleaned contact lens into a solution containing four different components: branched polyethylenimine (bPEI), catechol, polyethylene glycol (PEG), and urea. The bPEI acts as a polymer scaffold that’s functionalized by the other components: Catechol helps the resulting coating stick to the lens surface, PEG suppresses the adhesion of microorganisms and is known to keep surfaces from fouling with proteins, and urea repels water and enhances PEG’s antimicrobial activity. After dipping the lens in the solution, the researchers sterilize it in an autoclave at 121 °C.

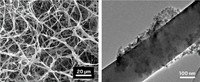

The researchers found that the coating stayed on the lens for up to seven days, keeping various eye-infection-causing bacteria and fungi from growing on the surface. It also kept proteins commonly found in tears from depositing on the lens. These protein films can reduce vision and sometimes mask antimicrobial layers, reducing their effectiveness. The coating did not cause a toxic effect on human cornea cells when a coated lens was placed directly on top of a cell culture over a 24-hour period.

The coating could be easily applied to daily and weekly disposable contact lenses available today, Yang says, and the one-step coating method could be integrated into the current lens manufacturing process. Her team is now optimizing the coating for a contact lens company that has expressed interest. The researchers also plan to test it in animals soon.

The new coating’s effectiveness against bacteria and fungi is valuable, Willcox says . “Manufacturers prefer as few steps as possible to coat lenses so as not to increase the cost of production,” he says, so the single-step process is a key advantage of this method. “And all contact lenses are sterilized by autoclaving,” he adds, so the fact that the coating retains its antimicrobial activity after sterilization makes it compatible with current manufacturing processes.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter